Decolonization and Chagos: An Unfinished Story

A Case Study of the Chagos

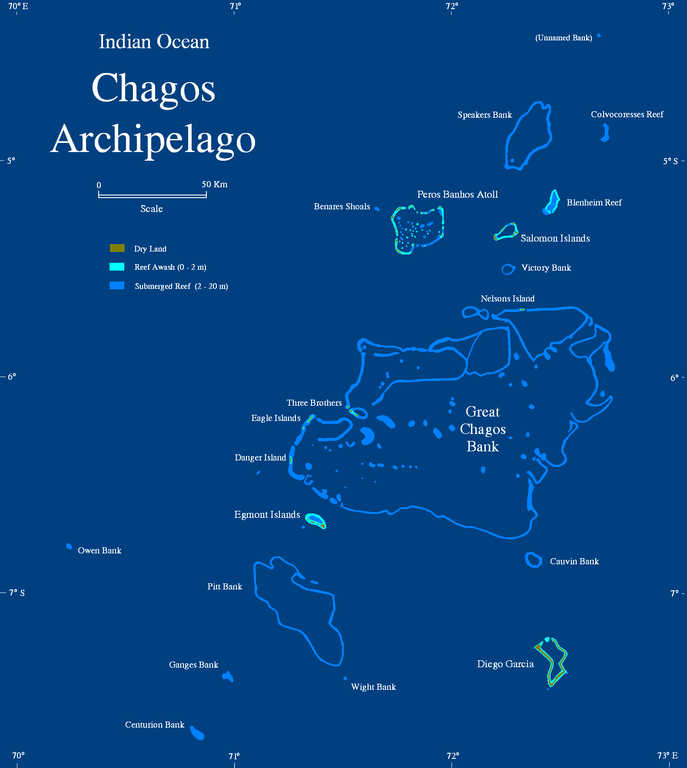

For the first time in almost half a decade, members of the Chagossian community can bask in the warmth of hope. Cries of joy resonated through the Chagos Refugee Group Centre in Port Louis, Mauritius, as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) delivered its advisory opinion on the 25th of January 2019. Their clamour for their rights to be recognized had not only been heard but also validated by the ICJ’s decision. Mauritius, an island located off the coast of East Africa, historically had a number of dependencies, including the Chagos Archipelago, a cluster of small islands strategically located right at the centre of the Indian Ocean. Ever since the excision of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1968 Chagossian natives have been prevented from returning home. The ICJ’s advisory opinion is a recognition of this major injustice, establishing that the process of decolonization of Mauritius was not lawfully completed and that the UK has an obligation to return the Chagos to Mauritius as soon as possible.

The magnitude of this achievement can only be grasped by considering the historical background to the long and arduous struggle that preceded it. Mauritius has been a Portuguese, Dutch, French, and most recently a British colony. Amidst negotiations for its independence from Britain, Mauritius was asked to relinquish control of the Archipelago. The UK then took over these islands, rebranded them as the “British Indian Ocean Territory,” and shortly thereafter expelled the indigenous population in order to make room for the US to build and operate a full-fledged nuclear military base on the islands. The Chagossian community has since lived as a people without a land, in Mauritius and neighbouring Seychelles. Although the British government provided a small compensation to Mauritius for those who had to relocate, no price can be placed on a person’s homeland.

Life in Mauritius and Seychelles has not been easy: Chagossians are very often treated as second-class citizens despite holding Mauritian or Seychellois passports. Many families were separated at the time of expulsion and their children have suffered the pains of growing up only knowing of their place of origin through stories and old, frayed photographs. It is because of the violation of its sovereignty and the pain and anguish inflicted upon the displaced islanders that Mauritius has been campaigning, at least since the early 1980s, to draw attention to the plight of this community and for their right to return to the islands. In order to accomplish this, this geographically exiguous state of just over 2000 km2 , with limited economic and political influence internationally has had to take on two of the most powerful nations in the world, the US and the UK. The ICJ’s advisory opinion is thus the fruit of a long-lasting diplomatic battle which many feared would never amount to much given the unlikely odds of David overcoming the political Goliaths it chose to confront.

The questions which were submitted to the ICJ were first whether the process of decolonization of Mauritius had been lawfully completed and second assessing the legal consequences of the continued occupation of the Chagos by the UK. The advisory opinion delivered by the ICJ not only condemned the acts of the British government at a time where it clearly wielded coercive power over the Mauritian government, but it also emphasized that the Chagos should be returned to its people as soon as possible. The only cloud dimming the otherwise blue skies many felt upon hearing the ICJ’s opinion was the lingering question: “What next?”

Many remain skeptical as to what the practical implications of the ICJ’s stand means as the reaction of the British officials has been dismal, with London insisting the fact that this was an advisory opinion and not a binding judgement per se. This unfortunately neither connotes remorse over its past colonial wrongdoings nor a desire to alter the present state of affairs. Moreover, this would not be the first time the British choose to remain indifferent to the situation despite a legal opinion. In 2006, when the High Court of Justice in London found that the Chagossian community were entitled to return to Chagos, the British government acted swiftly to circumvent the judicial decision. This is indicative of the extent to which stronger nations are sometimes able to escape the law by virtue of their political power and military might.

The Chagossian tragedy does not stop there. In addition to being denied their fundamental right to their home, many of the islanders fear that there may not be a home to go back to, due to the disastrous environmental impact of a military base. In 2014, reports surfaced according to which the US had been dumping large amounts of waste in the pristine Chagossian lagoon. Should those who were forced to leave the island in the 1970s go back today, would they even be able to recognize it, amidst such pollution? Moreover, the British government’s decision to establish a marine nature reserve around the islands in 2010 has been revealed, through a leaked diplomatic cable, as a ploy to ensure Chagossians would not be able to return to the island. The British government’s efforts to maintain control of the island does not stop at dismissing a court judgement but extends as far as enacting policy which purports to legalize and justify their claims. This comes across as a lack of respect both for International Law and for the Chagossian people. This leak also revealed that the Chagossians were referred to by the British in derogatory terms such as “Tarzan men” or “Man Fridays”, further emphasizing the extent to which this community is disrespected. These deeply unsettling facts demonstrate that the attacks on their dignity are not a mere relic of the past; it is being perpetuated time and time again, in various ways.

A defining component of the Chagossian identity, their homeland, was taken away from them decades ago. The emotional trauma that comes with being expelled from one’s native land is unfathomable. The pain of a people at the hands of a stronger nation operating in its own interests is reminiscent of the time when the world was divided into those who conquered and those who were conquered. To this day, the underlying power dynamics between the Chagossians and the UK is tainted with colonial exploitation. Can we really speak of independence and decolonization at a time when the fundamental right to a homeland is being undermined by the interests of a more powerful nation? Can we speak of equality and human dignity when this homeland which has been taken away from its natives is also being destroyed and the natives themselves are being marginalized?

It is in these moments that the true face of modern international relations between a former colony and its former colonizers reveals itself, in all its similarity to the past. These issues are not geographically limited to this archipelago of the Indian Ocean. The same narrative can be told from countless other parts of the world. Now more than ever, it is the duty of the UN to hold the British government accountable for its acts. As long as there exist visionaries and organizations such as the ICJ acknowledging injustice and daring to stand up to the more powerful in defense of the weaker, hope shall prevail. It is the responsibility of the international community to push for change and not let a nation get away with such horrendous acts by virtue of its geopolitical and economic power.

Contributor Ishika Obeegadoo is an undergraduate student at McGill University.