Democracy, Blasphemy and the Struggles of Being Indian-Pakistani

If Shakespeare wrote Romeo and Juliet in 1947, they wouldn’t be Italian, they’d be Indian and Pakistani. Sadly, my twin sister and I are the only ones in my family with this split identity as inter-marriage is considered taboo. It’s tough when your heart is split by the caged borders of the Radcliffe line.

The animosity between Muslims and Hindus in the region runs deep thanks to the scars left by centuries of colonial rule and religious violence – with minorities, such as the Christians, caught in the middle. Things only got worse after partition. Childhood friends became sworn enemies; Families were torn apart; the Bengali people were denied their own nation, and two million people died with another fourteen million displaced in the forced odyssey to their ‘designated’ homeland. In the eyes of the British Raj, Partition was meant to stop an impending holy war between Hindus and Muslims, but, sadly, it triggered it.

Seventy one years, a nuclear arms race and four wars later, India and Pakistan are at a crossroads. India is home to the ‘world’s largest democracy’ but is rife with widespread corruption, nationwide inequality, and institutionalized caste-based discrimination. Pakistan has devolved into a garrison state plagued by military praetorianism, depreciating democracy and a losing war on terror.

This past summer, cricketer-turned-Prime Minister Imran Khan was elected thanks to the promise of a naya (new) Pakistan which claims to usher in an era of greater minority inclusivity and economic development, but it’s failing miserably. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi champions the now-ironically regurgitated ‘world’s largest democracy’ mantra whilst ignoring millions of Assam state voters and alienating Indian Muslims across the country.

Democracy

All my life I’ve wanted to vote, to make a change, to be able to have a say in my country’s future. The reality is, the only time I’ve ever been eligible to vote has been during SSMU elections and referendums.

The country I was born and raised in doesn’t provide birthright citizenship and isn’t even a democracy – so that’s out of the picture. Then in 2013, when Pakistan miraculously avoided another coup d’état and had its first ever peaceful transition of civilian power, I missed the election. My relatives and family friends went back to Pakistan in droves just to vote, but I had to stay at home as I was only seventeen at the time – one year below the voting age. Since then, I counted the days to when I could actually vote; which would have been this past summer’s election. Once again, I missed out. As I’m considered an “overseas Pakistani”, with my very own “overseas” ID card, I was ineligible for the 2018 election despite the Pakistani Supreme Court saying otherwise. Once again, I sat in the sidelines as Imran Khan was controversially elected Prime Minister.

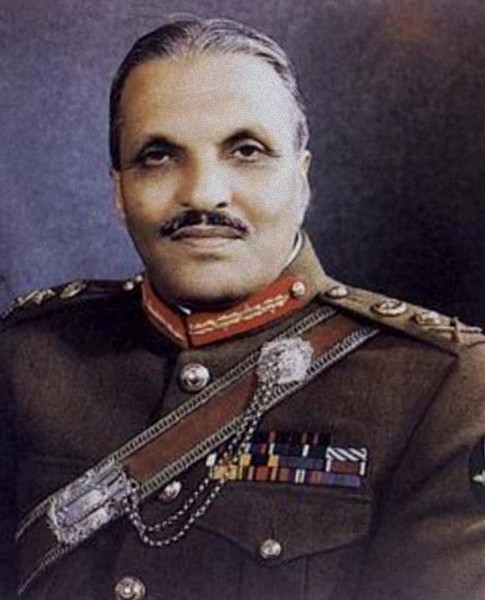

I wasn’t the only one slouched in the sidelines. As millions of Pakistanis cheered from the stands as Khan ran his victory lap – not as a world cup winner this time – the Ahmadis were also left apathetic. Making up roughly two percent of the total population, the Ahmadi Muslims are a minority sect that have been excommunicated from domestic politics and civil society. Ahmadi discrimination has become institutionalized and is sadly, socially accepted. In 1974, Prime Minister Z.A Bhutto’s 2nd Amendment declared them non-Muslim and later General Zia ul-Haq’s 1979 Hudood Ordinances stripped them of their human right to practice, profess and propagate their faith. Pakistani politicians have to swear an oath denouncing them before entering office and anti-Ahmadiyyas groups have called for their extermination.

Undemocratically, Pakistan is one of the only countries in the world that has two voting lists; one for Muslims, Hindus, Christians and all other religions, the other reserved for Ahmadi Muslims. Many of them abstained from voting this election but others were more optimistic about Imran Khan’s naya Pakistan.

On September 1st, Imran Khan made history when he recruited Dr. Atif Mian, a Pakistani Ahmadi economist, to his Economic Advisory Council to salvage the crippling economy. Within the week, he repeated history when he sacked Dr. Mian after public outcry. Arguably one of the most qualified and exciting young economists in Pakistan, Mian was fired solely because of his faith.

As a Sunni Muslim, it’s disappointing that despite helping draft the 1940 Lahore Resolution, and contributing two of Pakistan’s three Nobel Peace Prize laureates, the Ahmadi community is still banished from Pakistani civil society. For the Ahmadis, there’s no difference between the first hundred days of Imran Khan’s naya Pakistan and the past forty four years.

Since there’s no such thing as dual Pakistani-Indian citizenship, nor I doubt will there ever be, I’ve silently spectated every Indian election. Since Narendra Modi became Prime Minister in 2014, his and Khan’s tenures parallel each other: high on grandiose spectacle, low on effective policy-making.

Without diving into Modi’s economic catastrophes and political charades, there has been a disturbing development in India’s democratic integrity. This past year, in the Indian state of Assam, over four million people were left out of a national citizenship registry.

The Assam draft list, called the National Register of Citizens (NRC), was set up to identify illegal immigrants in response to the 1950 Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act as the region has historically endured unwelcome mass-migrations from main-land India and abroad. The NRC states that out of the 32.9 million people living in the border state, 28.9 million are considered citizens. The rest are either deemed stateless or ordered to migrate back to Bangladesh and Myanmar, despite many being born and raised on Indian soil. BJP National Chief Amit Shah even branded them ghuspetiye (infiltrators) and proclaimed that he would “find them one by one and send them away.” Despite, Modi’s promises of ache din (good days), millions are now counting how many they have left in their ancestral homeland.

Modi cannot label India the “world’s largest democracy” if his government excludes even a single citizen, let alone four million. Yes, there may be some Assamis who aren’t Indian by birthright but if India hopes to be a role model for the developing world, it must represent its native minority and disenfranchised populations as best it can.

Blasphemy

2018 has so far been a disastrous year for minority rights in the sister states. Uttar Pradesh, my mother’s home state, is being stripped of its Islamic heritage; Karachi, my father’s home town, is in lock-down thanks to Islamist hardliners, and hate crimes across both countries have skyrocketed.

Uttar Pradesh (UP) is the most populous state in India with a population of 200 million people, roughly the size of Brazil. UP also happens to be home to the largest concentration of Indian Muslims and Hindus in the country. Last year, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won by a landslide in the UP Assembly elections. Yogi Adityanath, a firebrand Hindu nationalist and Islamophobic monk, was then made UP Chief Minister. You can see where this is going.

If I had to sum up Yogi Adityanath’s political agenda, it would be to ‘make India Hindu again.’ His fervent conviction towards Hindutva (Hinduness) is no secret. Adityanath is infamous within the BJP for his brutal stance against minorities, specifically Muslims. He founded Hindu Yuva, a Hindu youth militia that has been responsible for communal violence against Muslims in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. His supporters have publicly endorsed the sexual assault of Muslim women, and their corpses. Last year, Amnesty International released a statement advising Adityanath to publicly retract his anti-Muslim sentiments. The only other time they released such a statement was against US President Donald Trump.

A few hours’ drive from my mother’s ancestral village is the city of Allahabad, which translates to the ‘City of Allah’. A former Mughal provincial capital with a rich Islamic heritage dating back to the 14th century, Allahabad is home to a quarter of a million Muslims making up 13% of the city’s total population. Recently, Yogi Adiyanath re-named the city to ‘Prayagraj’ as its geographic location is considered sacred to Hindus.

The move is a part of the ruling BJP party’s wider campaign to consolidate India’s Hindu identity by pushing aside its multicultural history. Utter Pradesh MP Surendra Singh proposed that the Taj Mahal be renamed to the “Ram Mahal” or “Krishna Mahal.” Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje has already re-named numerous ‘Muslim-sounding’ villages.

The BJP’s attempts at erasing India’s Islamic heritage raises many saffron flags for the future of the millions of Muslims and minorities living in India today. Since Independence, Sikhs’ have fled the country to avoid persecution and mob violence. Last Christmas, in Mathura city, Christians were arrested for praying in their own homes. Copies of the Quran and Bible have been publicly burnt. Beef lynchings have become routine. Mosques and churches have been stormed by violent mobs.

Minority groups and their heritage are reflections of India’s rich cultural diversity. Modi and Adityanath must realize that India is not the world’s largest theocracy, it is the world’s largest democracy and that means representing everyone who is a citizen under the Indian Constitution, regardless of faith.

When it comes to minority rights, the Pakistani state and civil society are guilty of numerous abuses. Alongside the aforementioned Ahmadi community, Pakistani Hindu, Sikh and Christian communities’ have also felt the wrath of Islamist hardliners.

On an everyday level, the root causes of Pakistani minority’s anxieties owe more to ordinary Pakistanis rather than terrorist groups. Non-Muslims are barred from ever becoming President or Prime Minister. Christian slums in Islamabad are targeted and demolished. Sikhs are regularly persecuted and are leaving the country in droves to India and abroad. In 2010, sixty Hindus were attacked by a mob and evicted from their homes in Karachi after a Hindu child drank water from a nearby mosque. In 2016, my freshmen year, I was shaken when sixty nine Christians were killed in a Taliban suicide bombing while celebrating Easter in a playground park.

Pakistan hasn’t always been like this. It was originally founded as a ‘West Minister-esque’ democracy with Islamic characteristics, but devolved into an Islamist garrison state following General Zia ul-Haq’s coup d’état in 1979.

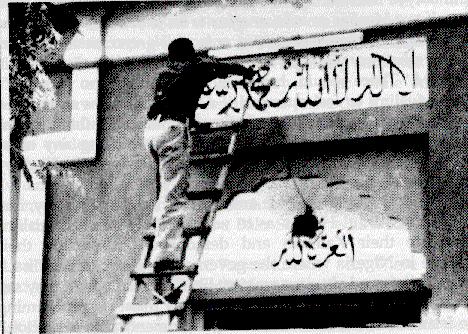

Pakistan has the harshest anti-blasphemy laws in the entire Islamic world, even more than the usual suspects like Iran and Saudi Arabia. In an effort to Islamize the nation, General Zia added numerous draconian clauses to Pakistan’s colonial-era blasphemy laws. One clause states that a derogatory remark against Islam carries a three year prison sentence. Another prescribes life imprisonment for “willful” desecration of the Quran. An offender can also be sentenced to death or life imprisonment for ‘blasphemy’ of any form against the Prophet Muhammad.

In 2010, Aasiya Noreen, a Christian Pakistani, was accused of insulting the Prophet Muhammad and was subsequently sentenced to imprisonment and death. This past month, after eight years of abuse in prison, Aasiya was found not guilty by the Pakistani Supreme Court. Senior Justice Khosa issued a statement saying that the accusations against Noreen “had no regard for the truth” and cited “material contradictions and inconsistent statements of the witnesses.”

Aasiya spent eight years in jail and was sentenced to death for a crime proven to be a baseless lie. But in that time, those who fought for her freedom paid the ultimate price. Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti and Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer were both assassinated in 2011 for opposing the blasphemy laws and advocating on Aasiya’s behalf. Their deaths were celebrated by hardliners across the country. Malik Qadri, Taseer’s killer and bodyguard, was later hanged but is still celebrated as a martyr. Pakistan’s Islamist hardliners lashed out against the Supreme Court’s decision and have even called for the Justices’ assassination, with one saying that “their security guards, their drivers, or their chefs should kill them.”

Today, in Karachi, hardliner gangs roam the streets, blocking roads, and attacking minorities on site. The civil defense is now mobilizing, Christian schools are closed, mobile phone networks are shut down, and families are forced to stay at home. Pakistan’s Toronto is now at a standstill.

Now, Khan has caved to the Islamist party Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP), one of the propagators of the protests, to stop the escalating violence from devolving into a state of emergency. In exchange, Khan has blocked Aasiya from leaving the country, confining her to jail for her own protection, and released arrested TLP rioters. The government has even banned news broadcasters from covering the Aasiya case moving forward.

Despite previously defending the judiciary’s decision, and threatening military action, Khan has failed Pakistan’s minorities. As long as Aasiya is still in Pakistan, she is not safe. Her family is not safe. The Christians, Hindus, Ahmadis, Sikhs and all other minorities in Pakistan are not safe.

The Struggles of Being Indian-Pakistani

Having a dual-identity isn’t easy for everyone. Being Indian-Pakistani is different from being American-Canadian, or British-Swiss. There are plenty of hybrids like myself who are prone to being alienated by their own heritages. Saudi-Iranians, Kurdish-Turks, and Taiwanese-Chinese, just to name a few, are forced to watch their conflicting identities be at each other’s throats.

Even whenever I’m around brown folk, I still introduce myself as an Indian-Pakistani, not one or the other. Every time both nations’ independence days come around, which are one day apart from each other, I proudly celebrate both historic days. Even though I may never be accepted by the state because of my dual-identities, I deeply care about both countries past, present and futures. I just hope that one day, whether it’s during my lifetime or after, things do change – for the better.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The McGill International Review or IRSAM.inc

Edited by John Weston and Milan Singh-Cheema

Special thanks to Aritra Samantha and Kody Crowell