Detroit: A Tale of Two Cities

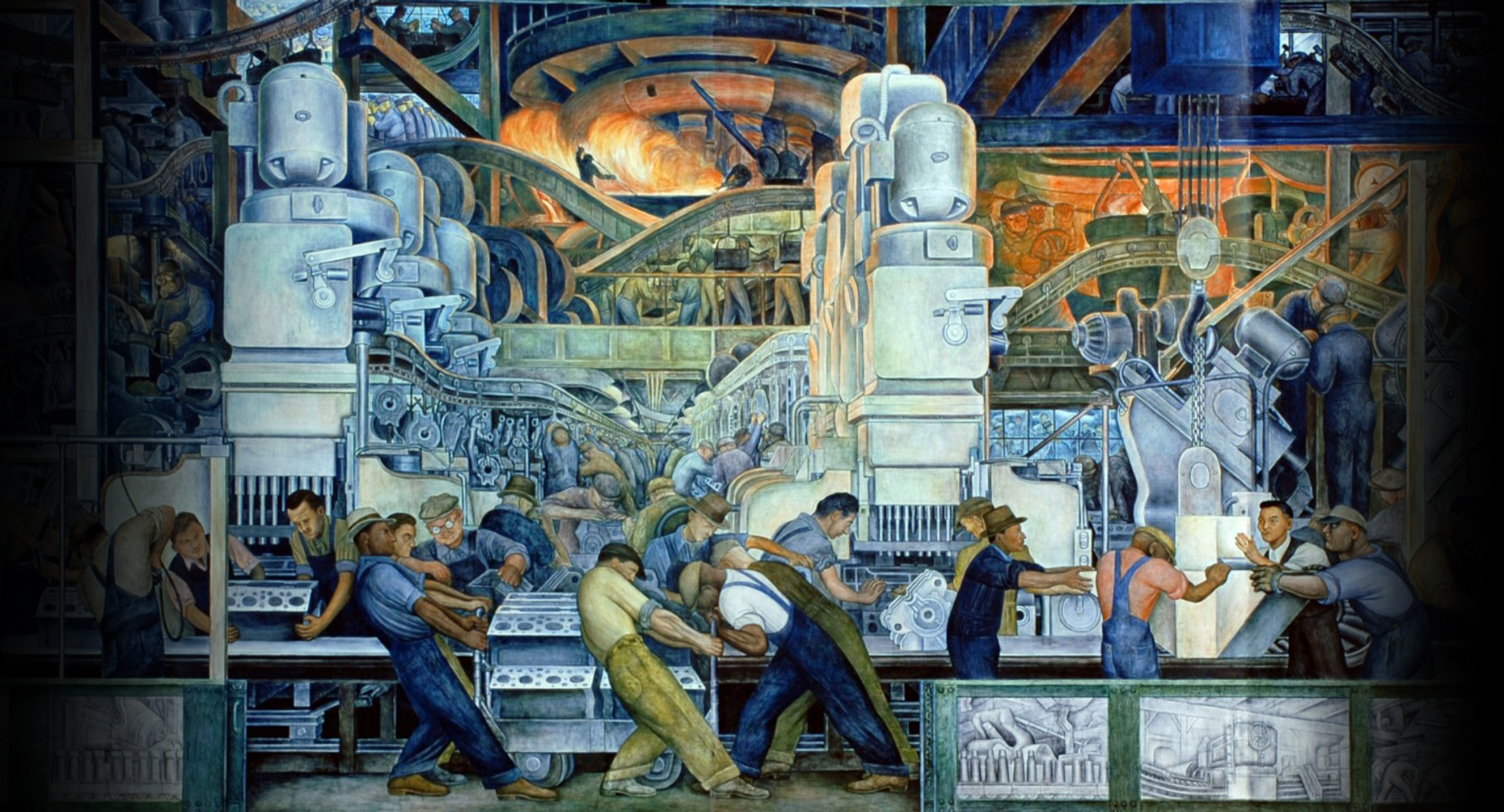

“The Motor City is burning, Ain’t nothing in the world I can do’’

John Lee Hooker sang these lines in 1967, as race riots enflamed East Jefferson. Formerly blossoming Detroit, where Hooker had made his name as a young jazz artist, was beginning its decline. In its prime, Detroit was America’s richest and 4th largest city[1]. Detroit played a very important psychological role in American society. There, the auto industry had helped to create relatively wealthy black neighbourhoods, where education and healthcare were readily available. The famous music scene emerged, playing a vital role in strengthening a sense of pride in the black identity.

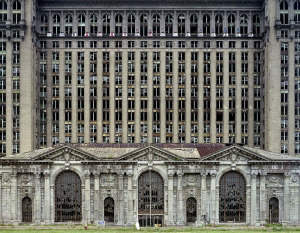

Those same neighbourhoods can be visited today, but all that remains are abandoned houses. Boarded up and falling apart, derelict homes now make up a third of the entire city. 25% of the city’s working-age population is unemployed and 50% are functionally illiterate. Homicide rates are equivalent to those of El Salvador[2] – a country recovering from civil war and struggling to deal with violent drug cartels.

Meanwhile, Detroit has gone from being 84% white in 1950 to 89% black today. Bankrupt and segregated due to the flight of wealthy, mostly white residents to the suburbs, Detroit saw over half of her residents have their water supplies cut off this summer. Rarely is this city mentioned without evoking crime and poverty. How could it be that the city in America with the highest average income in 1960 now has 60% of its children living in poverty[3]?

The usual explanation for the Motor City’s demise can be summed up in one word: globalisation. The narrative goes that with foreign competition challenging the dominance of American car companies and revolutionizing the automotive industry, industrial collapse in a city so dependent on one sector was inevitable. Capitalism’s process of ‘creative destruction’ hit an unprepared city hard, and it has not recovered since.

Dig a little deeper though and it transpires that this is only half the story. Industrial decline may have lit the fire, but it was government and corporate policy that fanned the flames that burned the city.

Hamstrung by $18 billion in debt[4], Detroit was forced to file the largest bankruptcy for a U.S. municipality last year. In the process, 21,000 retired residents agreed to see their pensions cut and the elimination of their annual cost-of-living adjustment. Behind this number there are people: policemen, teachers, attorneys and garbage men. They have been forced to pay the price of the mistakes of others.

There are three major aspects to the decline of Detroit: the effect of race on housing, the decisions of the ‘Big Three’ auto companies, and the economic policies of the federal government. Many analysts like to point fingers at corrupt local officials, in particular black mayors Kwame Kilpatrick and Coleman Young. In reality, this argument confuses the symptoms with the disease[5]; there were in fact few towns across the country without local governance issues at the time, which are exacerbated by larger factors, rather than being the sole source of the issues.

A rough welcome

Detroit’s boom began as early as the turn of the 20th century and grew exponentially in the following decades. Exporting all over the country and beyond, it was the period’s Silicon Valley, continuously innovating and employing. Black workers moved north to fill the shortfall of manual labour. This change in demographics, however, was anything but welcomed by the local population. Upon arrival, black families moving into all-white neighbourhoods were frequently attacked[6]: between 1945 and 1965, there were was over 200 such violent racial incidents. In 1949, Mayor Cobo ran his entire election campaign on the promise to keep white neighbourhoods white. Due to this division and since very little protection was available from loan sharks and predatory salesmen, blacks were routinely ripped off in the housing market. Eventually this led to Detroit’s black population being confined to poorer neighbourhoods.

This problem soon became self-reinforcing. In the wake of the great depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal included a huge push to increase home ownership rates. The Federal Housing Agency was created with the purpose of securing mortgages for all of America’s working class families. However, the scheme was universal in name only. It effectively recreated segregation north of the Mason-Dixon Line. Ta-Nehisi Coates explains in his piece The Case for Reparations[7]:

‘The FHA had adopted a system of maps that rated neighbourhoods according to their perceived stability. On the maps, green areas, rated “A,” indicated “in demand” neighbourhoods that, as one appraiser put it, lacked “a single foreigner or Negro.” These neighbourhoods were considered excellent prospects for insurance. Neighbourhoods where black people lived were rated “D” and were usually considered ineligible for FHA backing. They were coloured in red. Neither the percentage of black people living there nor their social class mattered. Black people were viewed as a contagion. Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage’.

Through this hateful, hostile encounter, ghettos were forged. At the same time, the social phenomenon of ‘white flight’ emerged, accelerating the process of ghettoization. Fearing falling house prices due to the presence of black communities, the white population of downtown Detroit moved to the suburbs en masse. Between the years 1970 and 2006 the city’s population dropped by more than 40%[8].

The first effect of white flight was to destroy the city’s tax base[9], since the highest earning income groups left, but the required spending on services they had accrued remained. Gradually schools and hospitals closed, whilst municipal debt soared. Secondly, manufacturing jobs followed the workers out of the city, relocating heavily in rural and suburban areas, where more modern factories could be built. By 1963, the city itself had already lost 140,000 manufacturing jobs to its suburbs. Driving around downtown Detroit today you see a staggering quantity of empty buildings that once depended on a thriving local community.

What could the government have done?

Federal and local authorities had both the power and ability to enforce non-discriminatory housing laws, yet they let ‘the FHA adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws’[10]. They could also have protected the black families at risk from predatory salesman and racial abuse. We might even venture to suggest that they could have taken a pro-active stance in integrating communities. However, none of this occurred, and black communities were impoverished by a combination of violence, scams, segregation and white flight.

School desegregation is a particularly good example of the shortcomings of the State. Although this was initially implemented with much success after the case of Linda Brown in 1954, it was unceremoniously ushered out in the 60’s and 70’s, now an artefact in the museum of failed social experiments. Its demise was spelled with the verdict of Milliken v. Bradley in 1974[11]. This Supreme Court trial, which subsequently affected all of the United States, was filed by the NAACP against the Governor of Michigan. It concerned 53 school districts in metropolitan Detroit[12]. The case, approved at the district level, argued that the city had enacted policies to increase racial segregation in these schools, contrary to their legal obligations. The Supreme Court subsequently overturned the ruling, stating that segregation was hitherto allowed if it was not considered an explicit policy of the school district. In other words, schools were not responsible for desegregation unless it could be shown that they had deliberately engaged in a policy of segregation. Unsurprisingly, this was the end of an abortive attempt at integration in Detroit, with schools being re-segregated along the lines of rich white and poor black neighbourhoods.

Things have only gotten worse with time. A 2014 UCLA study entitled ‘Brown at 60’[13] has found that, since the 1990’s, national desegregation attempts have effectively all ended. It goes on to assert that segregation now occurs simultaneously across race and poverty and is at its highest in the North-East – worst of all in Detroit. Unsurprisingly, it was also found that mixed education had a strong positive effect on lowering racial inequality. According to a 2011 study by the Berkeley public policy department, black youths who had spent five years in desegregated schools earned 25 percent more than those who never had that opportunity. The project was working, but was strangled in its cradle.

Thus, Detroit ceased to be the destination of choice for migrant labourers, but a place where they became stuck by virtue of segregation. Douglas Massey[14], a public affairs professor at Princeton says “unlike cities such as Chicago or Philadelphia, where segregation produced disinvestment in certain neighbourhoods, the nature of segregation in Detroit meant that the entire city suffered disinvestment”. The concentration of black communities in the city centre, around the old industrial parts of town, was the cue for a subsequent outflow of capital – both public and private. Affluent suburbs surrounded the increasingly isolated centre, where government expenditure was disappearing and corporations withdrawing.

Steering the wrong way

The irony in the decline is that nowhere was better suited to building cars than metropolitan Detroit; it had been designed for that sole purpose. The supply chain, transport links, human capital and infrastructure were all in place. The entire roadwork structure had even been designed to resemble the spokes of a wheel, centered on the colossal GM headquarters building, which continues to tower over the city – a reminder of its legacy.

The ‘Big 3’ (GM, Ford and Chrysler) played arguably the most important role in eliminating Detroit’s manufacturing. These three giants failed their hometown on several levels. Firstly, they responded too slowly and inadequately to the need for new fuel-saving technologies. After the first EPA regulations were introduced, such as the 1970 Clean Air Act, the Big Three were unresponsive and reluctant to adapt to the new requirements. No new models promoting fuel efficiency were developed, a reflection perhaps of the low incentives to innovate in the highly consolidated US market. This attitude continues today: according to a European Commission study[15] fuel consumption levels for US cars have not improved at all since the mid-80s. Subsequent rising global oil prices then accelerated the demise of US exports, as global markets no longer demanded the gas-guzzling American models, but rather the smaller, more economical European and Japanese cars.

Consequently, American firms have seen a steadily decreasing market share lost to more dynamic companies overseas. At the mid-century mark, the US had 75% of global car production, but today their exports are a mere 8% of the world total[16]. The Big Three have also been beaten in their own back yard, with their market share in America falling from 90% to under 60%[17].

The majority of the blame lies with the firms themselves. Their corporate structure was and remains highly focused on short term profitability. The executive power is concentrated in the hands of a few major shareholders, who push the need for immediate results above investment for the future. Research and development has been significantly more effective in European and Japanese firms, which is reflected in their quality and innovation. Management failures also made GM significantly less productive than their rivals in nearly every aspect of their operations, according to a Harvard Business School[18]. Business executives were unable to learn and develop new strategies, failing in particular in creating a good relationship between blue collar workers and directors, which made future wage negotiations very difficult.

Perhaps most tellingly, though, they responded to their own failures by deciding to move production out of Detroit in search of lower wages. The decision to move production out of Detroit was made on the premise that the unionised workforce had become overly expensive. The United Auto Workers (UAW) union[19], which has in fact been a lone voice in promoting racial harmony, was accused of demanding excessive wages. Production was first moved to the suburbs, then to the Southern states, and after that to maquiladoras in Mexico. This last step in the hunt for cheap wages was accelerated after the signing of NAFTA, after which a further 415,000 manufacturing jobs were lost as the auto firms raced to lower their labour costs. In fact, half of the top 20 hardest-hit districts by the trade deal were in Michigan, with the worst being Detroit.

These drastic measures were taken despite the fact that labour costs represented only 10% of total production expenses. Wages were, in fact, only marginally higher than in Europe and Japan, due almost entirely to the fact that the firms had to provide their own medical and pension schemes since the government didn’t. According to the Economist, each car in Detroit carried about $1,400 in extra pension and health-care costs compared with the foreign-owned competitors[20]. The big 3 used their unionised workforce as a scapegoat for their own inability to survive in the global marketplace. Of all the traditional major car producers, those which relocated the most aggressively were the Americans. They also simultaneously lost the most market share.

Again, we ask; how could policy have changed the outcome?

Evidently, a social security system, including access to medical care and a fair pension, would have made US firms more competitive. Taking these costs out of company overheads and into the public sector, like every other developed nation has done, removes a massive cost burden for enterprises. More stringent environmental compliance programmes would have encouraged the Big Three to be more innovative and attractive to foreign markets by forcing them to converge to modern international standards. One might even have envisaged a more proactive approach in slowing industrial decline and alleviating unemployment. Consider government funding of research and development, which may have significantly improved US firm’s competitiveness. The US, in 1975, spent only 0.6% of its GDP in state-subsidised research; this has consistently fallen since then to 0.4% today[21]. The current total stands at $140 billion[22], which is dwarfed by the $470 billion the EU spends[23]. Not to mention that in the US, R&D funding for the defense sector receives more than the entire non-defence sector[24], four times the figure for the EU.

Having destroyed Detroit’s comparative advantage, the government then used the benefits of globalization to justify the plight of its discontents. Those made redundant in Detroit as a consequence of corporate decisions and government inaction were further abandoned, as no major fiscal investment, support or training schemes were instituted. As firms embraced cheap labour south of the border, the authorities acquiesced, content to let the service sector make the most of the low tariffs they had negotiated. Meanwhile, Detroit lost 48% of its manufacturing jobs in ten years, with no aid to relocate the laid-off workers. In fact, Detroit receives only $108 million in federal aid per year, less than is given to 32 foreign nations[25]. This somewhat insulting statistic is highly indicative of the approach taken by the authorities: the losers in free trade are abandoned.

In 2008 the great recession hit and the financial survival of the Big Three looked uncertain. The government stepped in, providing $80 billion of loans to help bail them out, a fraction of the $700 billion made available for the banks. Part of this deal included the ‘tiered wage system’, where firms accepted large wage reductions, undoing settlements previously acquired by the UAW. A few years on and the companies now have recovered to remarkable levels of profitability. Whilst paying off their loans at rates lower than the average mortgage, share prices have reached new peaks[26]. Real wages in the economy, though, have continued to slip since the crisis, despite productivity gains of 7.7%[27]. The workers have seen any of their sacrifices repaid. In fact, GM are now in such good shape that they plan to open 4 more plants in China over the next 3 years[28], which seems all too soon considering that their bail-out was financed by tax-payers, including those of Detroit. For an industry that was on the verge of collapse to turn its back in this was on those who saved it is a remarkable display of ingratitude.

When looking at the panoply of disastrous decisions made by the shareholders and directors of the Big Three, deeper questions about the structure of these corporations arise. Yale economist Richard Wolff summarizes[29]:

‘What kind of a society gives a relatively tiny number of people the position and power to make corporate decisions impacting millions in Detroit while it excludes those millions from participating in those decisions? When those decisions condemn Detroit to 40 years of disastrous decline, what kind of society relieves those capitalists of any responsibility to help rebuild that city? The simple answer to these questions: no genuinely democratic economy could or would work that way’.

Federal government made little to no attempt at alleviating the problem. The policy of benign neglect which has characterised US industrial policy over the last 30 years has been inconsistent and short-sighted. The needs of cities like Detroit were overlooked, whilst others sectors and firms were spoiled with favours. Inconsistencies in federal support are sometimes even less subtle than this. A little known fact is that in 1975 the city of New York filed for bankruptcy and was granted a $2.3 billion direct loan from government[30]. Support to the fiscally troubled city then continued until 1986. No such loan has been considered for Detroit.

Rivers and Roads

Since the bankruptcy, things have been hard for the people of Detroit. Thousands currently live without water – a basic human right according to UN law[31] – as families are unable to meet their bills. The Detroit Water and Sewage Department (DWSD) announced in March, and subsequently commenced, plans to cut off water for “homes with delinquent bills” at a rate of 3,000 homes per week[32]. Out of 700,000 residents, 300,000 will have lost water within the end of the year. That’s just under half of the city. In a pitiless warning, the DWSD recently tweeted “if you’re stealing water, we’re coming after you”. They failed to clarify their understanding of ‘stealing’ though, which some might actually accuse them of doing, seeing as water prices have risen 120% in 10 years.

Unsurprisingly though, they did find it within their hearts to write off the bills of their corporate partners at the Detroit golf course, the Joe Louis Arena and the Ford Field[33]. Not far from these golf courses and stadiums are sights of black and brown Detroiters walking down major avenues, carrying water tanks atop their shoulders, scenes usually associated with war-torn nations in which US intervenes.

Unsurprisingly though, they did find it within their hearts to write off the bills of their corporate partners at the Detroit golf course, the Joe Louis Arena and the Ford Field[33]. Not far from these golf courses and stadiums are sights of black and brown Detroiters walking down major avenues, carrying water tanks atop their shoulders, scenes usually associated with war-torn nations in which US intervenes.

National media has created a sense of collective pity for Detroit by illustrating “the post-apocalyptic hellhole” as an aberration, a blight on the map, cut off from the “prototypical” American experience. It should be understood, though, that Detroit is a fundamental part of the modern American model. It is the flip side to the financial center in New York and agricultural surpluses from the plains. It was indispensable in creating modern America and, for all its flaws, is a part of the national identity. Boasting the merits of the US system of governance in creating powerful international firms without mentioning Detroit is, in the words of Coates[34], à la carte patriotism.

We almost lost Detroit, Gil Scott Heron used to say. We’ve lost a great deal already. But looking ahead, things may be different. The IMF forecasts that the world will have nearly 3 billion new cars by 2050. Detroit remains, on many levels, a great place to develop automotive industries. The Chinese have already understood this and are beginning to invest in Motor City[35]. Now it remains for government and corporate policy to learn from past mistakes and engage in a proactive development plan.

Detroit tells a story of race and money. It is a tale of two cities, the one it might have been and the one it is. Whether we come to speak of the new Detroit for what it will be, or what it might’ve become, is the challenge ahead.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/07/22/detroit-decline-cause-auto-industry-segregation-race_n_3635818.html

[2] http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/GSH2013/2014_GLOBAL_HOMICIDE_BOOK_web.pdf

[3] http://mic.com/articles/45563/detroit-bankrupt-to-see-detroit-s-decline-look-at-40-years-of-federal-policy

[4] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-07-19/u-s-automakers-thrive-as-detroit-goes-bankrupt.html

[5] http://www.urbanophile.com/2012/02/21/the-reasons-behind-detroits-decline-by-pete-saunders/

[6] http://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol2no1/sugrue.html

[7] http://www.theatlantic.com/features/archive/2014/05/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

[8] http://www.clevelandfed.org/about_us/annual_report/2013/index.cfm?DCS.nav=Local

[9] http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/07/the-decline-and-fall-of-detroit.html

[10] http://www.theatlantic.com/features/archive/2014/05/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

[11] http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=418&invol=717

[12] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/20/opinion/sunday/integration-worked-why-have-we-rejected-it.html?_r=0

[13] http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/news/press-releases/2014-press-releases/ucla-report-finds-changing-u.s.-demographics-transform-school-segregation-landscape-60-years-after-brown-v-board-of-education

[14] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/douglas-s-massey/segregation-the-invisible_b_777323.html

[15] http://ec.europa.eu/environment/enveco/policy/pdf/2007_automotive.pdf

[16] http://www.oica.net/category/production-statistics/

[17] http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/automobile_industry.aspx

[18] http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/14-062_29ad7901-c306-44fa-88df-31e97a17cbbf.pdf

[19] http://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol2no1/sugrue.html

[20] http://www.economist.com/node/13783014

[21] http://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/RDGDP_0.jpg

[22] http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42410.pdf

[23] http://ec.europa.eu/research/infrastructures/index_en.cfm?pg=structural_funds

[24]http://www.esa.doc.gov/sites/default/files/reports/documents/thecompetitivenessandinnovativecapacityoftheunitedstates.pdf

[25] [25] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/07/31/detroit-bankrupt-federal-aid-colombia_n_3683740.html

[26] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-07-19/u-s-automakers-thrive-as-detroit-goes-bankrupt.html

[27] http://www.epi.org/publication/a-decade-of-flat-wages-the-key-barrier-to-shared-prosperity-and-a-rising-middle-class/

[28] http://www.autonews.com/article/20130420/GLOBAL03/130429994/gm-plans-to-add-four-more-plants-in-china

[29] http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/jul/23/detroit-decline-distinctively-capitalist-failure

[30] http://www.propublica.org/special/bailout-aftermaths#nyc

[31] http://www.righttowater.info/wp-content/uploads/BOOK-1-INTRO-WEB-LR.pdf

[32] http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/07/detroit-water-behind-crisis-2014727123440725511.html

[33] http://www.dailykos.com/story/2014/06/24/1309265/-Detroit-Shutting-Off-Water-to-Thousands-Every-Week-as-Desperate-Citizens-Appeal-to-U-N-for-Help

[34] http://www.theatlantic.com/features/archive/2014/05/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

[35] http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/jul/22/does-multimillion-dollar-chinese-investment-signal-detroits-rebirth