A Different Shade of Green: Is a New Kind of Green Movement Behind Iran’s Recent Protests?

The recent protests in Iran—besides being the largest in the country since the Green movement took to the streets in 2009—have also fueled furious speculation regarding the protests’ causes. This speculation has been as diverse as it has been furious, with analysis ranging from the responsibility of egg prices to the growth of Christians in the country. Curiously enough, one particular angle that has been neglected in the discussion is one which has dominated the Iranian political climate in the recent elections—namely, the environment.

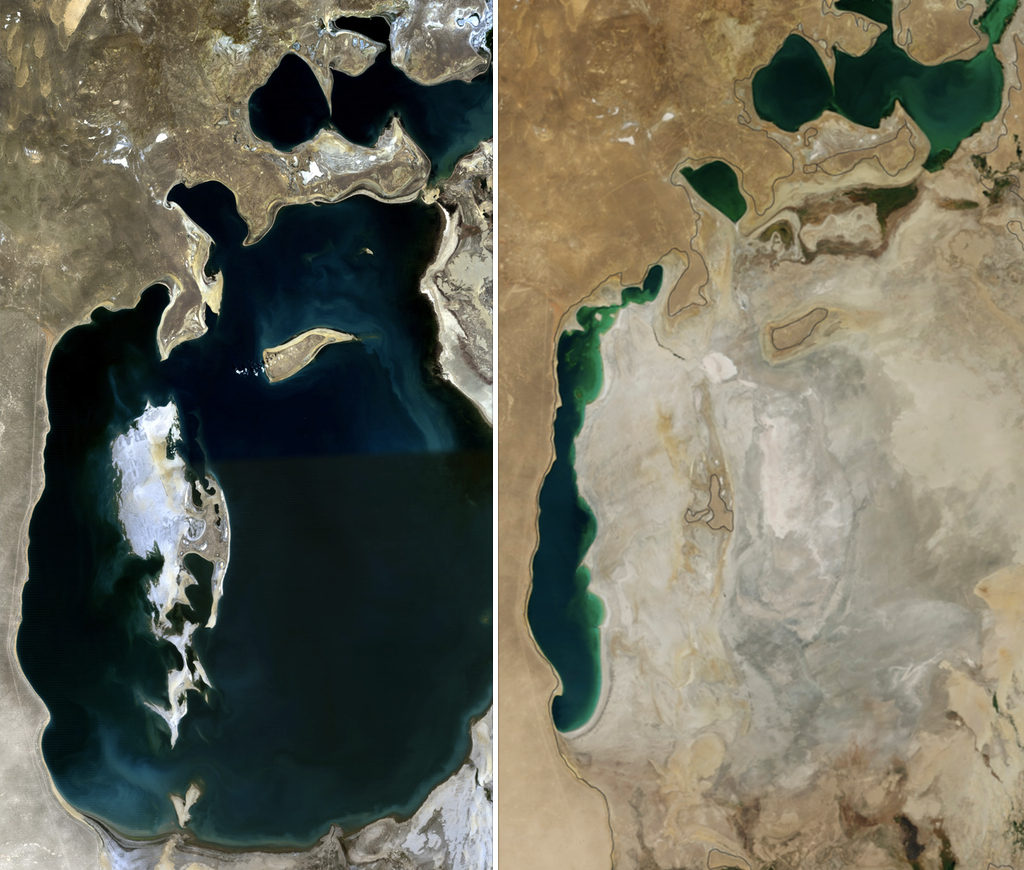

When the subject of environmentalism is brought up in the context of the Middle East or Central Asia, attention is usually directed toward water. There is good reason for this. For many, the world map that adorned the wall in their childhood school is now outdated; an entire sea which was once universally featured has almost entirely disappeared. According to a 2014 UNEP report, the Aral Sea, a body of water straddling Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, has less than 10 percent of its former volume of water.

While the case of the Aral Sea is indeed a highly conspicuous example, what is more troubling is that it is only an indicator of a multitude of larger, less visible problems across much of western Asia, most recently including Syria, Pakistan, and Yemen.

Iran has its own Aral Sea — Lake Urmia. Located in the northwest of the country, the lake, Iran’s largest, has been steadily shrinking since the 1970s. In 2015, it was estimated that it had shrunk by nearly 90 percent. The effects have been varied and devastating. For wildlife, the increased salinity level due to the lake’s desiccation has placed the ecosystem in jeopardy. In 2010, it was reported that the lake had reached a salinity level of 340 g/L. This has threatened the habitat of a brine shrimp known as the Artemia urmiana, a staple in the diet of many local animals. The lake’s decrease in size has also had many adverse effects on humans, impacting local tourism, devastating agriculture and crop yields, and the health of those who live in the surrounding areas. Moreover, the lake is an important symbol for the identity of Azeris, an ethnic group inhabiting northwestern Iran, who call the lake “the turquoise solitaire of Azerbaijan.” Should Lake Urmia be resigned to the same fate as the Aral Sea, the effects on both people and ecology, in Iran and abroad, would be even more devastating than they already are at present.

Just as the Aral Sea is not an isolated case in western Asia, neither is Lake Urmia in Iran. Elsewhere, a separate series of water crises are taking place. Another instance is in the southeastern province of Khuzestan. The province used to be an extensive wetland, however, recent history has seen many of the marshes dry up and the remaining water become polluted. The loss of fertile soil for agriculture, increased dust storms, and air pollution are among a wide array of symptoms that the region is experiencing. While the roots of Khuzestan’s problem are numerous, Ahmad Savari, a professor at Khorramshahr’s Science University, attributes responsibility to the fact that “hectare after hectare of the wetland was given away for oil extraction.”

This factor has also led to four Iranian cities occupying places on Time’s “The 10 Most Polluted Cities in the World,” largely due to the air pollution caused by oil extraction and refinement. Indeed, Iran’s environmental crises, whether water shortages or air pollution, are as interconnected as they are widespread.

Recently, in the aftermath of the blizzard that hit Tehran, Iran’s deputy environment chief, Masoud Tajrishi, declared that unless there is a change in water consumption patterns, Iran will become “water-bankrupt.” His comments come at the end of Iran’s driest period in 67 years.

The urgency of the problem, however, has not been entirely ignored. In 2016, Iranian actor Reza Kianian began a social media movement to raise awareness for Lake Urmia, using the tag “#IamLakeUrmia” (من دریاچه ارومیه هستم#). This increased public focus on environmental issues in the public consciousness as well as in the media has transferred over to the arena of Iranian politics. In the prelude to the elections of May 2017, many candidates, particularly moderates, began shifting their focus towards these issues. One example is Alireza Zaman Kharqani, a parliamentary candidate in Qazvin province who included packs of seeds in his campaign brochures in order to encourage reforestation. Other presidential candidates, such as Mostafa Hashemitaba, a former minister of industries and vice-president, called water and environmental problems “one of the main challenges of the country.” Likewise, former vice president Mohammad Reza Aref called environmental problems a “top priority” and “a national threat.” This was further reflected by the now re-elected president Rouhani, who used the improvements in Lake Urmia to bolster his record of working group success stories. Rouhani also made environmental issues the center of his political platform, forging a plan that elevates water issues to the same status as the economy and security.

Besides their newfound importance in Iranian political campaigns, environmental issues, especially water, have proven to be contentious, triggering violence and upheaval in a multitude of trans-national contexts. As reported by MIR in January, the current political phenomenon of water shortages in central Asia left former Uzbek president Islam Karimov warning that “Water resources could become a problem in the future that could escalate tensions not only in our region, but on every continent.” Elsewhere in the Middle East, this is already a reality. Water shortages have not only been a major issue for local populations, but are a major factor in current conflicts. In the case of Syria, some experts have suggested that a major drought in 2006 pushed the rural population toward urban centers, which in turn provided the impetus for anti-government protests. In Yemen, a similar trend of urbanization led to unsustainable water consumption, exacerbating already existent tribal tensions and providing the stimulus for the civil war. The ongoing insurgencies in both Somalia and Nigeria also demonstrate how water instability can provide the unrest necessary for militant groups such as al-Shabaab and Boko Haram to legitimize their takeover of administrative powers traditionally held by the regional governments.

Unlike in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, or Nigeria, however, a civil war or major insurgency has not recently occurred inside Iran. While that is the case, there is a striking parallel in the manifestation of major protests over environmental issues. One such instance is a series of protests in 2015 which broke out following a major dust storm in Khuzestan. The dust levels, reported to be 66 times above the healthy level, were attributed to the failed handling of the environmental crisis by the Rouhani administration, thus prompting the anti-government demonstrations. Similar demonstrations erupted in February 2017, after a dust storm caused the central power station in Ahvaz, the capital of Khuzestan, to stop working. With the recent protests at the end of December which began in Mashhad and spread to Tehran and other major cities, Khuzestan was very much a part of this larger movement, playing host to some of the longest and most violent demonstrations. At the end of January, another crisis, this time a dense smog, rolled across Khuzestan reportedly leaving 1,530 people hospitalized. Faced with the reality that inaction on the part of the government would result in further protests, Rouhani was pressured into pledging $100 million to “combat particles.”

Protests, such as in Khuzestan, demonstrate the direct connection in Iran between environmental crises and the grievances behind unrest. Iran, according to this model, fits the pattern of resource unrest that has also appeared in Syria and Yemen. Just as Khuzestan’s dust storms are connected and a part of Iran’s environmental issues, so too are they indicative of the dynamics of protest across the country.

There are signs, however, that the Iranian government is beginning to take note of this reality too. Recently, the arrests of several environmental scientists, and even the death of a Canadian-Iranian dual citizen, have suggested that authorities are beginning to target both the major sources of information regarding environmental crises as well as critics of the government’s response to these crises.

Iran not only fits Islam Karimov’s prophecy of “escalate[d] tensions,” but provides a model of how water is bound up with other environmental problems and can ultimately lead to internal conflict and protest against the government. Before any other issues, such as the rise of Christianity in Iran, can be read into the protests, an understanding of the issues that dominate the Iranian political climate must be given priority, lest protesting Iranians lose their agency to the hands of a Western media which have been so excited to paint a picture of its own.

Edited by Shirley Wang