Eating Pure and True: Halal Businesses in China

Food safety has always been problematic in China. After the 2008 milk scandal, in which an estimated 300,000 babies were made ill from contaminated milk that was reported to contain melamine, demands from society have driven the food industry to implement further scrutiny. Reporting on food safety violations has rocketed in recent years, thus making many people seek safer food options with either imports or local alternatives. Domestically, halal food has become an especially common alternative. In China, halal products are called qingzhen, meaning “pure and true.” Since there is no national organization that officially certifies halal food and since the “halal” title symbolizes that certain food is prepared according to Muslim traditions with generally stricter regulations than average Chinese food, the certification process falls under local Islamic organizations like the China Islamic Association. Driven by the high demand for halal food, the sector is growing rapidly, increasing 6.4% per year. Nevertheless, while the halal sector does provide a seemingly trustworthy alternative for domestic food products, it has been controversial. Halal food has created a policy dilemma for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP): to help promote halal business for economic purposes or to stick to an atheist set of socialist values. This dilemma is only further complicated by the growing Islamophobic rhetoric heard on social media from Han Chinese, who are deeply unhappy with China’s changing religious and economic landscape.

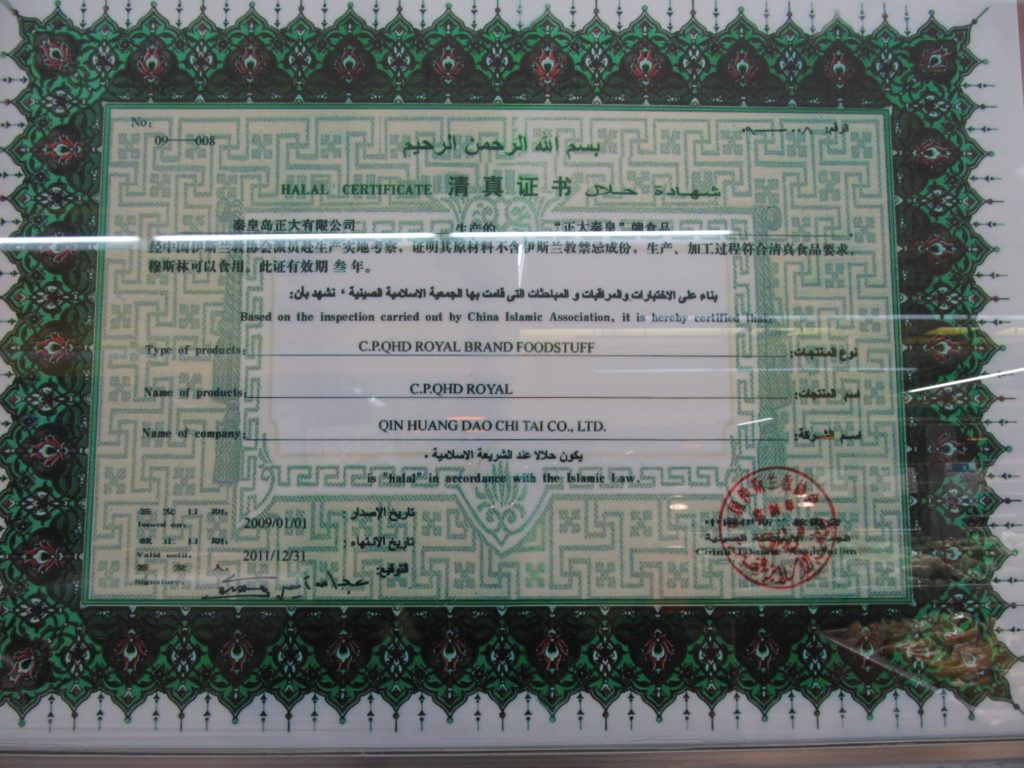

The growth of the halal sector has indirectly led to growing Muslim influence in the northern province of Gansu where the ethnic population is predominately Hui, a Muslim minority. Unlike Xinjiang’s Uyghurs who speak a Turkish dialect, Hui Muslims speak Mandarin and are often indistinguishable from their non-Muslim neighbours when not wearing their burqas or white caps. The Hui people’s cultural differences stem from their distinct culinary practices and religious beliefs. Halal businesses are often started and run by these Hui minorities, who incorporate their religious practices into the preparation and marketing of food under the certification of qingzhen. To acquire the certification, a unique procedure has to be performed by an imam who prays over the slaughtering of animals and conducts other religious rituals according to Quranic doctrine. This distinction prohibits many restaurants and businesses from acquiring the certification because Muslims want to preserve the holiness of their food. If non-Muslims want to apply for the certification, they must follow all the Quranic guidelines detailed by the China Islamic Association. Since some believe that the halal symbol represents a safer food choice, many non-Muslim food industries want to increase their competitiveness and attract more consumers by acquiring the certification. Whether the owner of the business is Muslim or not, the halal sector has thus emerged as a competitive food provider in the Chinese economy.

This certification process, however, has sustained criticism due to its lack of regulation. Since there is no national standard for the process, the granting of the certification is subject to the judgment of local governments and sometimes local Islamic associations. Mandatory religious rituals during food preparation give some economic and political power to imams, who supposedly only serve as religious leaders approved by the CCP. In some villages in Gansu, imams even have stronger cultural and religious influence than the local government: they lead daily prayers, utilize money from the halal sector to build mosques, and encourage the study of the Quran in schools. This influence has even reached past imams’ original spheres of influence in Muslim-populated regions.

This increasing religious influence conflicts with the national policy of religion below the state. The CCP has consistently emphasized that all religious practices should be under state regulation and that they cannot interfere with policymaking. Gansu and its neighbouring autonomous region, Ningxia, seem to be diverging from the wishes of the CCP.

The growth of halal sector imposes two threats and contradictions on national policies. Under President Xi, the halal sector has been subsidized and enjoyed tax-free zones to compete with neighbouring Southeast Asian countries on the production of halal food. In addition, Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative has sought opportunities to establish bilateral trade agreements with Muslim countries for halal business. These state policies have allowed the sector to grow immensely, even while the Party’s more atheist principles may contradict these economic incentives. The political status of Ningxia as a “Hui Autonomous Region” has further complicated policymaking. On one hand, Hui minorities are allowed self-rule and the practice of their beliefs; on the other, local governments are required to accomplish national mandates. The central-local relationship between local officials and the state poses the question of whether the local officials should align themselves more with Beijing or associate themselves with local halal businesses who provide them with economic benefits. This balancing game exposes the potential danger of the CCP losing its grasp over religious groups: if local officials bow to halal businesses’ economic interests, they may be giving a green light to the expansion of religious organizations’ influence.

This potential danger has manifested itself in widespread fear among the Han population that, if the halal sector keeps increasing, China will witness an Islamizing movement justified by economic forces. The debate surrounding halal businesses and increasing Islamophobia was particularly heated in 2016 when the CCP was said to be considering standardizing halal business regulations due to several halal food scandals after 2013. Anti-Islam sentiments in regards to the rise of halal foods have maintained momentum even until today. This trend on the internet is increasing cleavages between ethnic groups and possibly subjecting Muslim minorities hate speech.

With its religious influence expanding, the halal sector has received much backlash on social media and from society. Many Han Chinese have voiced their discontent with the growing presence of halal businesses in non-Muslim regions. The halal sector does not limit itself to the dairy and meat industry. Halal-only canteens have begun to appear in some universities; salt, soy sauce, and other necessities are becoming qingzhen-certified; and stories regarding Muslim segregationists circulate on social media. Meituan, a food delivery service, has adopted a Halal-only delivery box to expand its customer base. This Meituan controversy has been viewed by some internet users as a plot to destroy national ethnic unity and advocate a Muslim identity above the rest of the population. One person wrote on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, “Muslims need a separate box even for a delivery, you can see how they treat us, the non-Muslims one day… Meituan you are helping them to hinder us. I will never use your service.”

Similar and more violent posts can be found online. There are calls from Han communities to resist buying qingzhen–certified products, and criticisms of officials in universities and local governments have been gaining momentum since 2017. Critics of halal food have gone so far as to accuse Muslims of betraying the core values of Chinese society, which currently centre around the new Xi Jinping Thought to create a socialist society with Chinese characteristics and with the Party as supreme arbitrator. Within his rhetoric, President Xi has stressed that religions should be Sinicized and, therefore, serve the interests of the CCP.

With momentum growing, it has the potential to turn violent, either online or in reality. This potential places the national government in a critical position: choosing between supporting economic growth in the halal sector or addressing the grievances of the Han people, who constitute more than 90% of the country’s population. During the 19th Party Congress, President Xi demanded that China “actively guide religions to adapt to the socialist society” and impose further regulation on religious associations. Nevertheless, this rhetoric seems unable to reconcile the conflicts between halal supporters and halal objectors. There is a lack of actual regulation on the ground to curb halal business, and violent anti-Islamic posts are censored on the internet. The grievances of the people have not been addressed properly since their calls for stricter regulations of halal businesses have not been answered by the State Religious Affairs Bureau. In fact, CCP has banned the use of anti-Islamic words online, and halal sector is still expanding. The growing trend of Islamophobia and attacks on Muslim culture and values is extremely problematic; yet at the same time, the idea of an Islamic “penetration” into China worries many Han Chinese. The CCP, unclear on whether it will draft regulations on the halal business, is becoming more repressive in its rhetoric toward the Muslim minorities. How the CCP will decide to balance its economic interests and atheist core values will determine whether the growth of the halal industry or Islamophobic rhetoric will win this round.