The End of an Era: Can Trump and Brexit be Good for the Economy?

2016 has been a historic year in the Western liberal political tradition. Events like the Brexit referendum in June, and the election of Donald Trump as the 45th President of the USA in November have created much uncertainty about the future. More than anything, these democratic results prove that the globalized free market system, revered by most modern economists, is simply not working for large parts of the world. Most economists, political pundits, and news media have lampooned Trump, and the Leave campaign on the feasibility of their economic plans. However, considering their grand miscalculations in the past year, the credibility of their predictions has come into question. Can a certain degree of protectionism, in fact, be good for the economy?

Belief in the advantages of free trade dates back to the century, when David Ricardo came up with his theory of comparative advantage. In short, this holds that open markets benefit everybody because each economy can specialize in activities in which it has a competitive advantage, thereby maximizing global economic efficiency.

However, countries like the USA, and the UK have a competitive advantage in capital-intensive sectors, compared to Asian countries who have an upper hand in labour intensive industries due to their low labour costs.This means that according to Ricardian theory, manufacturing has predictably moved to Asia, since the region can produce more at cheaper rates. While free trade may produce cheaper products at a more efficient rate, it creates winners and losers. The winners are consumers in general, because they enjoy an incredible variety of products at lower prices. International businesses and traders are also beneficiaries of free trade. However, the losers in this case are American and British workers who have seen their manufacturing jobs outsourced to other countries where wages are lower.

To be laissez-faire in approach, the demand and and supply of labour should lead to the movement of laid off workers to more efficient industries. In reality however, labour movement from one sector to another is far more arduous than what Adam Smith or Ricardo would have liked. Whether it is a skills mismatch, inconvenience of location or emotional attachment to jobs, labour movement does not follow traditional free market principles.

Moreover, no country truly adheres to a pure form of the free trade theory. For instance, most countries protect “essential industries” such as agriculture, and defence to a certain degree using subsidies, tariffs, and quotas. American taxpayers spend around $20 billion a year on agricultural subsidies, in order to protect domestic food production.

In fact, the East Asian growth model, called the “Developmental State Model” has relied upon robust state led- capitalism to achieve export-led growth. Japan in the early 1960s, and Korea in the 1970s imposed punitive tariffs on imports to nurture favoured industries. In recent years, China has employed a spectrum of non-tariff barriers to grow chosen sectors without outside competition.

While the World Trade Organization has laid out rules and regulations of free trade, countries have been accused of breaking them to further domestic economic interests. China, in particular has been accused of “distorting competition by subsidizing loss making companies and dumping excess material on to international markets at unfairly low prices”. European and American manufacturing has taken a hit because their markets have been flooded with cheap imports. These “unfair trade practices” amid other perceived ills of globalization have led to a rising tide of economic nationalism in the West.

Can Trump and Brexit be Good for the Economy?

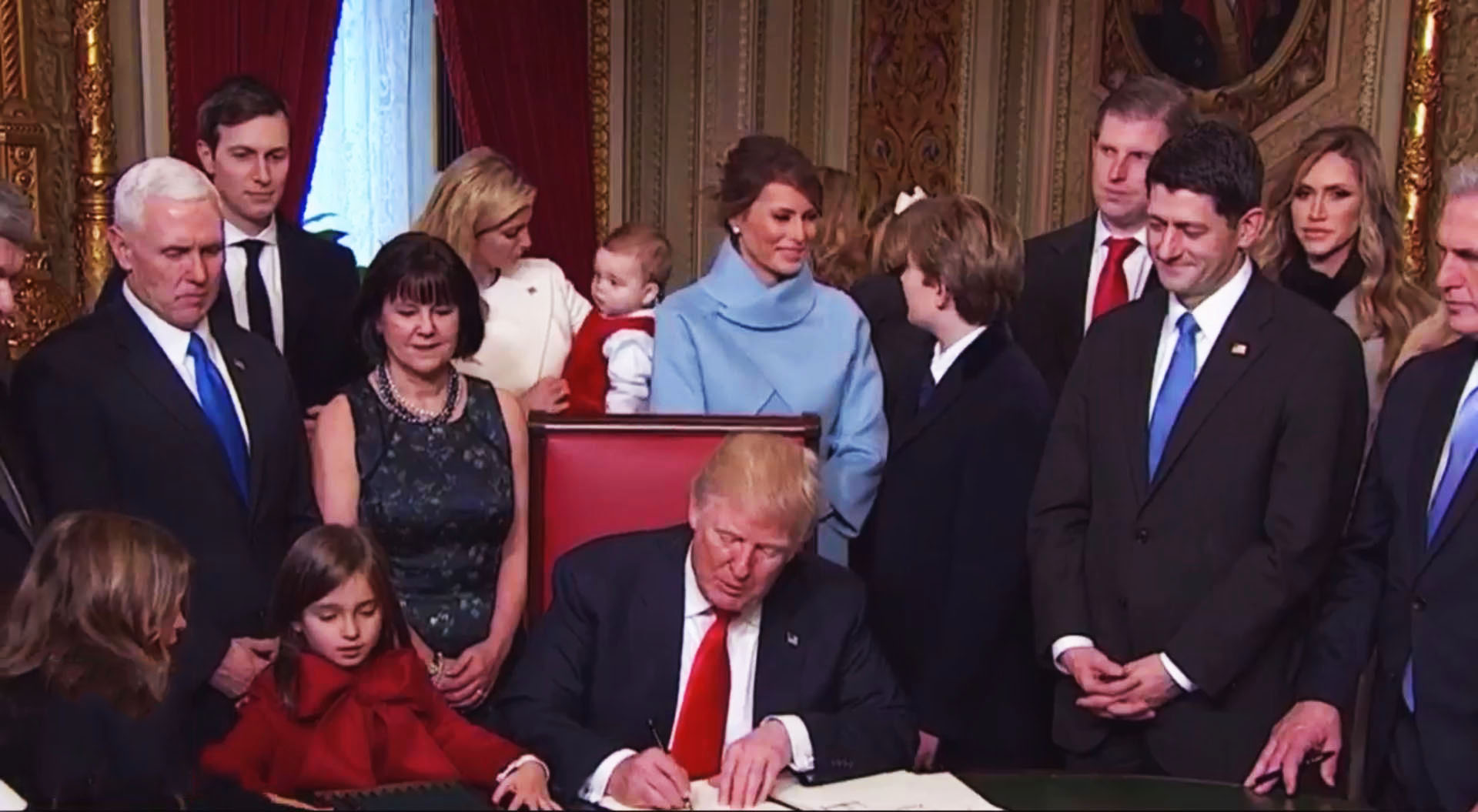

While the details of UK’s Brexit plan have not been disclosed yet, Trump’s economic plan has been the subject of excitement, incredulity, and hysteria. A unique combination of economic nationalism, huge tax cuts, deregulation, and high fiscal spending, the president-elect’s blueprint is not conventionally Republican.

Firstly, Trump’s campaign rhetoric was blatantly protectionist, proposing a massive 45% tariff on Chinese goods, dismissing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). If implemented, these tariffs on Chinese products could result in a disastrous trade war. However, his economic advisor, Peter Navarro claims that these hyperbolic stances will be used as a negotiating tool to broker deals that further American growth. The economist purports that Trump’s plan will reduce America’s trade deficit, and provide a $1.74 trillion gain in revenue by 2026.

Another contentious proposal in the plan is regressive taxation, reducing the top tax rate from 39% to 33%. According to the Tax Policy Center, the top tenth of a percentile of earners will see an average tax savings of 14%, while the middle fifth of earners will see a reduction in taxes of 1.85%, and those in the bottom 20% will only see a reduction of less than 1%. However, Steven Mnuchin, Trump’s newly nominated Treasury Secretary, asserts that caps on tax cuts, and childcare benefits for all will help the middle class. Trump has also proposed a cut in the USA’s unusually high corporate income tax by more than half to 15%. He explains that the cut would incentivize American companies to invest, and expand domestically.

Trump’s economic plan also emphasizes deregulation across government departments. His economic advisor, Anthony Scaramucci has highlighted the importance of simplifying tax codes and cutting regulations by 10% across regulatory agencies to send a pro-business message in the country.

Moreover, high fiscal spending in infrastructure is a surprising facet of Trump’s otherwise conservative domestic policy. According to the OECD, the president-elect’s promises of spending on infrastructure as well as tax cuts should lift U.S. demand, hence spurring investment, and boosting overall output – increases that should also spill over into the rest of the world. The Paris-based organization sees the global economy expanding by 3.6 percent in 2018, the fastest pace since 2011.

Lastly, he has promised to continue social security spending, besides reforming healthcare. Navarro asserts that by cutting the trade deficit, incentivizing domestic business growth, and deregulating especially the energy sector, the economic plan will offset its deduction in tax revenues, and increase in fiscal stimulus. However, multiple economic research institutions have revealed that Trump’s plan would expand national debt by trillions. For instance, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget concluded that Trump’s plans would contribute $5.3 trillion to the national debt. Thus, while Trump, and his advisors claim their plan is fiscally neutral, its lack of detail, and his constant shift in positions make it impossible to predict its consequences. The president-elect has tempered his stances on Obamacare, and Clinton’s emails since his election, and may follow suit by revising his economic plan as well.

Coming to Brexit, its long term economic impact depends on the UK’s withdrawal agreement with the EU. According to a Price Waterhouse Coopers report, UK growth is expected to slow to around 1.2% in 2017 because of the drag on business investment from increased political and economic uncertainty following the Brexit vote. In the long run however, the UK economy could benefit from “a more tailored immigration policy, the freedom to make trade deals, moderately lower levels of regulation and savings to the public purse”.

With nationalist rhetoric high in France, Hungary, and Austria, the globalized integrated economy is being shaken at its foundations. However, what will follow may not be crippling protectionism but trade with more emphasis on domestic economic policy.