Facing Our Favourites: What “Tintin” Can Teach Us About Social Responsibility and Cancel Culture

https://www.pexels.com/photo/brussels-bruxelles-tintin-405384/

https://www.pexels.com/photo/brussels-bruxelles-tintin-405384/

The last “Tintin” comics were published in 1971, but their social implications have never been more relevant. Hergé’s comics following the iconic Belgian reporter are an international phenomenon. Despite being a symbol of intergenerational nostalgia, the earliest editions present a problematic ideology the world is just starting to grapple with.

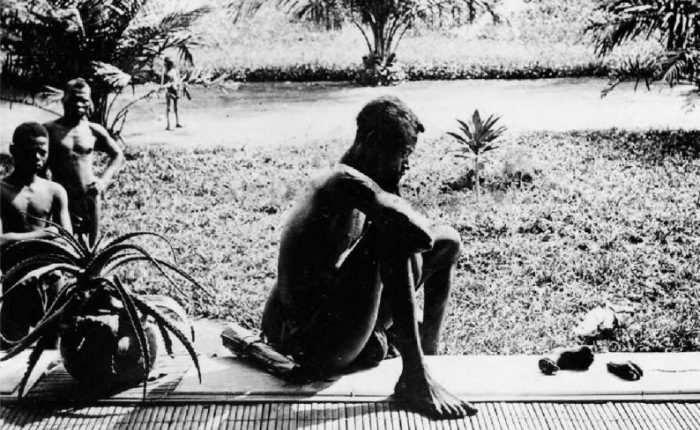

“Tintin in the Congo”, the second volume of the comics, came out in 1931 and featured the title journalist travelling to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Once there, he proceeded to remark on how “primitive” the locals were and attempted to make them more “civilized” by trying to get them to dress and behave as he did. Seven years later, the release of “The Black Island” saw Tintin travel to Scotland, where his interactions with the Scottish locals were strikingly different from his interactions with the Congolese locals. In contrast to the exaggerated and alienating features of the locals in “Tintin in the Congo”, the locals in “The Black Island” were humanized. They weren’t caricatures or stereotypes, and their culture, although portrayed as different to Tintin’s own, wasn’t mocked or belittled. Instead, Tintin attempted to become more like the locals to accomplish his mission, and, in doing so, donned a kilt. Laurence Grove, leading “Tintinologist” from the University of Glasgow, says that “[t]he Black Island is the key story stylistically and also ideologically” where the comics went “from looking at other cultures from the outside to taking on other cultures”. The extent to which such a claim is true remains to be seen.

To understand the damning effects of Hergé’s portrayal of Congolese natives in “Tintin in the Congo”, it is important to take a step back and understand the history of Belgian colonialism. Belgium ruled what is now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1908 until 1960 and the regime was largely characterized by its brutality. Millions of natives were violently coerced into labour for the rubber industry. Perhaps the most notorious example of this violence was the severing of workers’ hands for failure to meet rubber collection quotas. Brutality justification efforts from the Belgian colonists included convincing the public that people subject to their mistreatment were subhuman, and therefore, their distress wasn’t comparable to proper human suffering. They did so by mocking traditional Congolese lifestyles as “primitive”, pointing to a lack of automated technology as evidence that these people were more similar to animals than “civilized” Europeans. They depicted Congolese people as caricatures of themselves, giving them exaggerated lips, noses, and bodies until they were no longer recognizably human.

This is the setting for “Tintin in the Congo”, and these are the ideas that the comic echoes. And so, despite the glaringly racist depictions of the Congolese in the comic, it’s glowing reception at the time is no surprise. Most of the comic’s early readers were Belgians, and in a world where they saw these Congolese natives as subhuman, it isn’t hard to see why readers wouldn’t object to Tintin “civilizing” them or the reference of him as “[their] Master”.

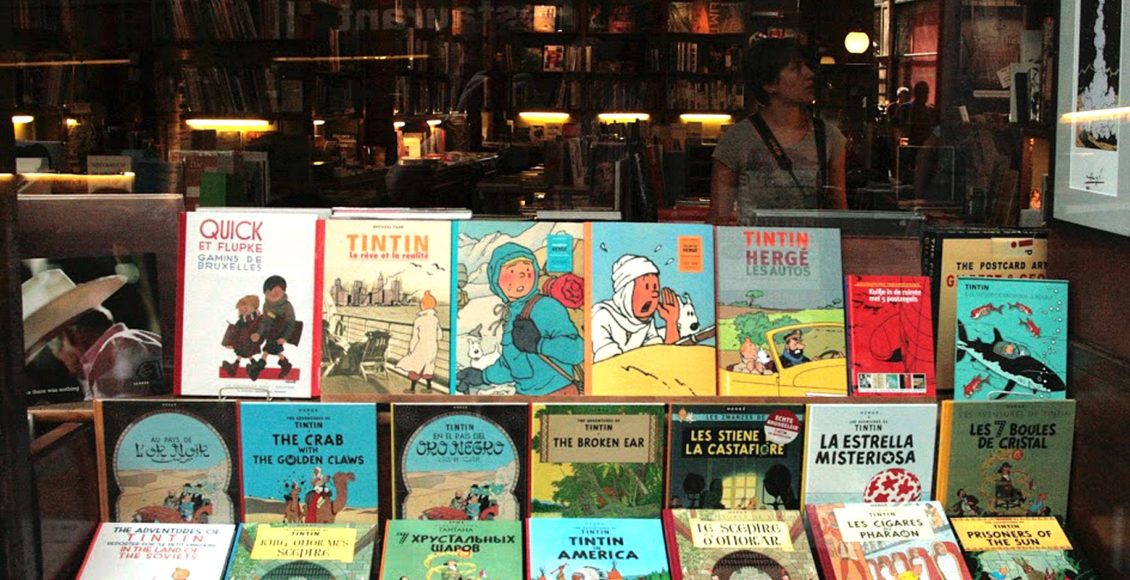

To place a work in its historical context, however, is not to absolve it of social responsibility. We can understand why a work was acceptable at the time of publication, but that doesn’t change the fact that the implications of the work endure long after. “Tintin in the Congo” can still be found in millions of bookstores and libraries worldwide, and recent editions remain largely unchanged from what they were in the 1930s. The only difference now, is the tolerance for such kind of content.

How, then, is this 80 year old comic relevant to our world today?

As our ideas of entertainment evolve, so do our demands of content creators. It’s not that the public has suddenly woken up and decided to consume responsible media; rather, over time, the number of people who’ve started caring about consuming work that isn’t outwardly racist or otherwise problematic, has increased, and “Tintin” isn’t the only work experiencing this phenomenon.

Social media has undoubtedly catalyzed this increase. Information is a lot more accessible now, meaning that people who previously didn’t have the means to educate themselves on experiences outside their social bubble can do so with ease. Furthermore, it’s significantly easier to spread ideas that change the way people think. Some social media movements have even worked to create tangible change outside the digital realm. For example, the #StopFundingHate campaign took to Twitter and Instagram to encourage companies to cut their ties with UK newspapers that were promoting anti-migrant sentiments. Their campaign was successful; massive corporations such as LEGO and the Body Shop disassociated themselves with those newspapers and publicly announced their commitment to bettering themselves. More recently, social media has also popularized the concept of cancel culture. “Cancel culture” refers to the, now-common, practice of publicly calling out an often powerful person or piece of work on problematic behaviour and encouraging others to stop engaging with or supporting it.

While bans and boycotts have been used for centuries, their effectiveness in the “pre-social media” era were not as striking. In 2007, the libraries in Brooklyn, NY banned all copies of “Tintin in the Congo” after a reader complained that they were “racially offensive”. The head librarian added that the books were deemed “inappropriate for children” and, as a result, were placed under lock and key. Despite being one of the clearest examples of blacklisting, this decision garnered little discussion. People generally didn’t seem to care: those who had never read “Tintin” found little reason to start, and those who wanted to read this particular volume could still find it in one of Brooklyn’s hundreds of other bookstores.

Today, the difference in effecting lasting change lies in social media. Not only does it make it easier to spread ideas: it makes it easier to find or cultivate an audience that’s willing to listen to your ideas. And, with the rise of “cancel culture”, this audience is increasingly more willing to boycott not one volume or one episode or one book, but rather, the entire work under scrutiny.

Collectively boycotting a work might sound tempting, but it’s important to acknowledge some of its inefficiencies. For one, it discourages people from trying to work on changing their views; they see no point in trying to adapt their views if they will no longer be consuming the work in questionif they’re always going to be tied down to what they did before. If, for example, we had “cancelled” the Tintin comics, we might never have hadthere wouldn’t have been the opportunity to talk about it and shed light on its social implications. Hergé’s attempt at fixing his past mistakes vis-a-vis “The Black Island”. This spot light and the attention it carries On the other hand, the attention an issue receives– is now be magnified by the reach of social media and can be enough to garner long-lasting change.

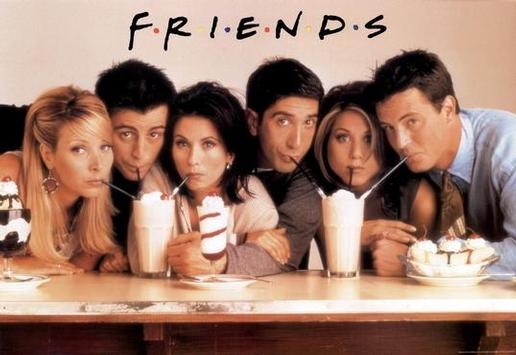

That being said, there’s a difference between “cancelling” individuals who have problematic views and “cancelling” entire works of art (such as books, movies, comics, etc.). While the permeation of harmful opinions is generally limited by the time and energy put into spreading these beliefs, the social effects of entertainment, both temporally and spatially, is essentially timeless. We’re still talking about the social impact of a comic book from the 1930s. We still talk about problematic jokes in our favourite TV shows – think Friends – decades after they came off the air. The truth is, we continue to consume entertainment long after it’s been released, which means that its potential to hurt or misrepresent people far outlives its creators.

Surely, then, we must hold entertainment to the same high standards we do individuals. We – both as a society and as individuals – need to develop the language for addressing these issues; as we all become more socially aware, we can revisit the more problematic aspects of works that might have previously been accepted. As this happens, we need to allow for both the creators of those works to grow and change their future work, and continue to have conversations about how the affected groups feel about the works in question.

I still love the Tintin comics. I own several collector’s edition volumes – though notably not the second one – and read them whenever I need a dose of childhood nostalgia. Through the years, I’ve learned that my love for these comics as a whole not only can, but must, coexist with my criticism of them. The only way I can allow myself to be a fan is by acknowledging the past and engaging in conversations about it as often as I can, and being open minded that other peoples’ experiences might not be the same as mine.

This is an incredibly new problem. We’ve only just started becoming collectively aware of the pervasive racist, sexist, homophobic, or otherwise problematic undertones in the entertainment we’ve loved since we were children. It might be tempting to solve new problems with new solutions, but cancel culture might not be the panacea for all our entertainment ills. Perhaps the solution is even simpler than we anticipated. As we become more socially conscious, it’s essential to learn to love and criticize works in equal measure. To work towards reconciling a problematic past with its amended future, we must bring each other into the conversation, not cancel each other out.

Edited by Shaista Asmi.