Faltering but Firm: Why China’s Grip on Myanmar Isn’t Going Anywhere Just Yet

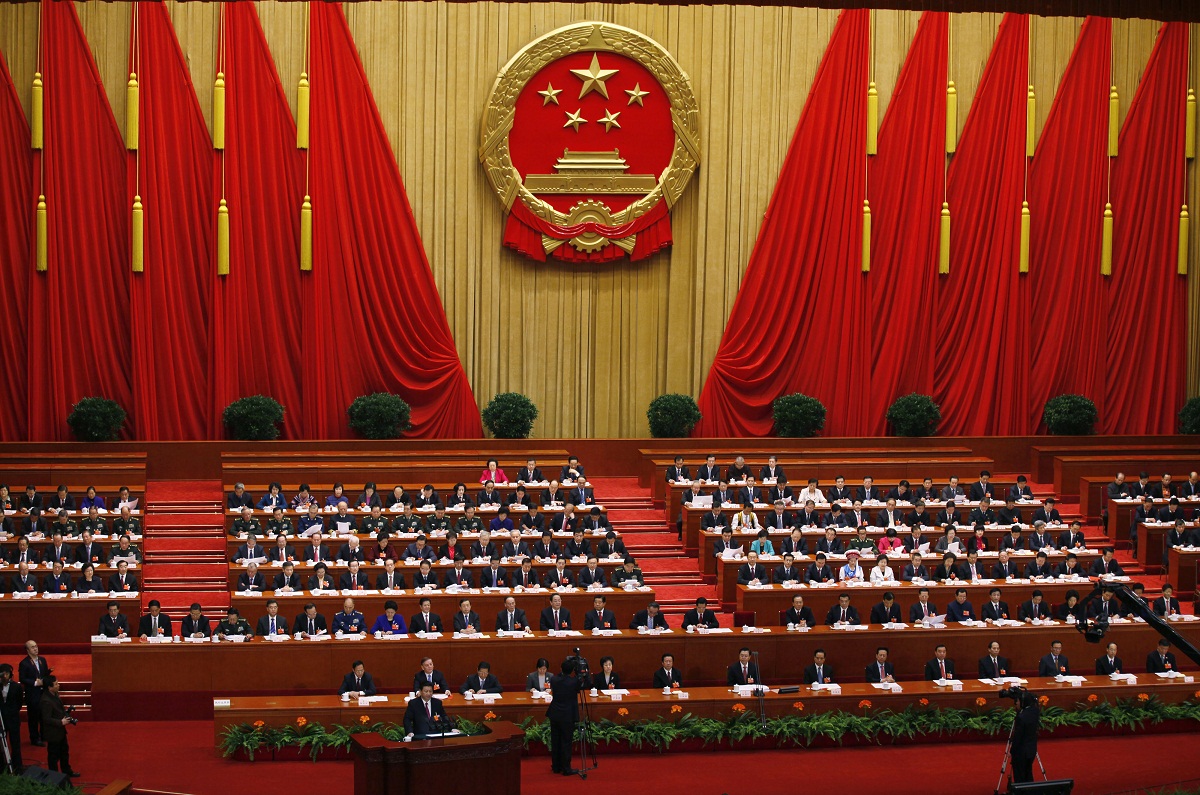

Beijing will keep a close eye on the developments in Myanmar https://flic.kr/p/fVe9oG

Beijing will keep a close eye on the developments in Myanmar https://flic.kr/p/fVe9oG

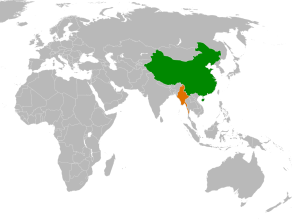

Aung San Suu Kyi’s recent diplomatic trip to Beijing at the end of August should put to rest Chinese fears of losing influence in Myanmar. Recent developments in the past year have seemingly signified that Myanmar was beginning to look at breaking away from their friendly relations with Beijing. However, a successful visit with Suu Ki, the leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD) and the de facto leader of Myanmar, means that for now, China can feel reassured.

Developments in Myanmar over the past year have been increasingly worrisome for Chinese leaders. The election in November of last year within Myanmar was the largest shift the country has seen in some time. It marked the end of the long-standing military control – under the guise of the State Peace and Development Council – that was largely stimulated by Chinese support. The convincing victory of the NLD has spurred a shift in ideology for Myanmar. This was the first time a democratic group had been elected in a fairly free election since the failed attempts to do so in 1990.

This was an ideological shift that China was not keen to let spread across the border. In addition, despite constitutional laws barring Suu Kyi from officially ruling in Myanmar and the military still holding 25% of the parliamentary seats, the NLD did not fail to act quickly to address the problems that plagued the country. Addressing these problems once again brought the relationship between Myanmar and China to the forefront.

In 2011, Myanmar suspended the work on the joint $3.6 billion USD evaluated Myistone dam project between the country and China. While environmental concerns were given as the official explanation, many believed it was a move for Myanmar to distance themselves from their neighbours. As the NLD began their time in office, protests erupted across the country to ensure that the project remained dormant. In the weeks preceding Suu Kyi’s visit to Beijing, the dam further remained as a point of discussion, with many pleading for their representative not to cave to Chinese demands. The growing anti-Beijing sentiment amongst the Burmese citizens was just another cause for concern for the Eastern power.

These growing concerns for China meant that reconsolidating the strong bond between Myanmar and China was of vital importance during Suu Kyi’s diplomatic visit. The fact that her world tour would eventually lead her to Washington only reaffirmed the sense of urgency within the Beijing camp. Therefore, when both sides finalized the five-day trip by highlighting their commitment to the long-standing “fraternal friendship” between the two countries, China had very knowingly made a big step in consolidating their influence within the region.

This stamp of approval raises questions for Myanmar. For while maintaining peaceful international relations with China may seem like the pragmatic course of action for Suu Kyi, it puts the country in the crosshairs of not only its own domestic base, but also its fellow Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members due to the growing concerns over the South China Sea. Yet, Myanmar has too much to lose by alienating China, and the NLD will need to focus on consolidating democracy in a country with a largely nonexistent democratic history. Maintaining the status quo within their foreign policy will in part allow them to turn their attention to more pressing domestic concerns.

Thus, despite the subsequent and apparent success of Suu Kyi’s trip to Washington in the middle of September, it does not look like the West will pull Myanmar out of the Chinese sphere of influence just yet. While Obama’s commitments to strengthen relations by increasing capital flow and ending the national emergency classification of the country may assist in creating a line of communication between the West and Myanmar, there is still a lot of ground to cover and China simply has too much of a head start. Of course, Myanmar can accept support from both great powers, but it will still have to give preferential treatment to Chinese demands.

There are also realist policies at play that will further aid Chinese attempts to maintain their current relationship with Myanmar. With Chinese support and arms being provided to local militia groups like the United Wa State Army it means that the Chinese have a very real stake in the ongoing attempts to quell ethnic divisions within Myanmar. It provides China a level of control that the United States cannot hope to match.

This is also without taking into account the geopolitical benefit that China has in terms of geographic and economic ties with their southwest neighbours. This is a country that accounted for nearly all the foreign stimulus in Myanmar while the military junta still held power. While the Southeast Asian country was shunned by the international community, citing human rights violations amongst other concerns, China continued to circulate capital across the border. Self-interest driven or not, this remains a huge benefit for China and a crucial involvement for the Myanmar economy. While the promise from Obama to lift sanctions against Myanmar, and other countries like Norway and Switzerland hoping to assist with the internal peace talks, Western involvement cannot hope to match the dependancy Myanmar has on China.

Regardless of the growing democratic wave within the country, the renewed sense of optimism, and the anti-Chinese movements from the Burmese people, Myanmar is not likely to distance themselves from Beijing in favour of Washington. The recent discussions between the two Asian states seems to have confirmed as much. While the factors that threaten to separate the two continue to exist there will always be a question mark over the relationship. If Myanmar can consolidate peace within its borders and turn its attention to its international commitments there may be an expiry date on its Chinese dependency. In the interim however, China can rest easy knowing they won’t soon lose Myanmar from their tight political grip.