#Fedidwgugl: The Dangers of Pragmatic Centrism and Coalition-Building in Germany

This Sunday, 24 September 2017, about 61.5 million German voters will elect a new Bundestag. Many expect the incumbent Christian Democratic Party (CDU/CSU) Chancellor, Angela Merkel, to win a historic fourth term in power. Merkel’s three terms in office since 2005 have been inherently characterized by coalition governments – two of which were ‘grand coalitions’ contracted with the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD), and one with the classically liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP). In the relatively quiet lead-up to the federal elections, it seems that the Christian Democrats will need to engage for a fourth time in coalition-building to secure leadership in government. A renewal of the governing CDU/CSU-SPD coalition seems unlikely, however, as Social Democrats tire of their junior position in government. By contrast, a CDU/CSU-FDP coalition seems increasingly likely, while a CDU/CSU-FDP-Greens alliance could be another option, should the conservative and liberal seats not suffice to form a majority in the Bundestag. With only days to go before the federal election, coalition-building seems inevitable – and with it, the continued instrumentalization and fragmentation of the German political landscape. The myth of German exceptionalism can only do so much to prevent the rise of illiberalism in the margins.

Coalition-building is inevitable. Most polls concur in predicting that six political parties will attain the 5% threshold allowing them to sit in the Bundestag – the CDU/CSU, the SPD, the Left (Die Linke), the Greens (die Grünen), are likely to be joined by the Free Democrats (FDP) and the Alternative for Germany (AfD). The polls also predict a comfortable victory (about 37%) for incumbent Chancellor and Christian Democrat Angela Merkel. Merkel’s main contestant is Martin Schulz, a Social Democrat (SPD, centre-left) and former President of the European Parliament. Despite a remarkable surge in support in the first months of 2017, the SPD candidate has since fallen back in the polls (22%), in what is considered to be one of the worst Social Democrat campaigns in years.

Although the conservatives will continue to dominate German federal politics, they will need to engage in coalition-building to secure their position in parliament, as they have thrice done since 2005. In large part, the inevitability of coalition-building in Germany is rooted in its mixed-member proportional representation system. The CDU-CSU will need to choose between two winning coalition-building options: it can either renew the incumbent ‘black-red’ coalition (CDU/CSU-SPD), likely securing over 60% of seats in the Bundestag, or forge the first three-way coalition with a ‘black-yellow-green’ or ‘Jamaica’ coalition (CDU/CSU-FDP-Grünen), likely securing over 55% of seats.

It should, however, be noted that a number of Social Democrats – including Matthias Miersch and Dietmar Nietan – have expressed strong feelings against returning as a junior partner in Merkel’s ruling grand coalition. The overall sentiment is that the SPD was “really used by Merkel” and that it would do better in opposition. Should Martin Schulz put the grand coalition to a vote in the SPD, as he has promised and as had been done in 2013, a renewal of the CSU/CDU-SPD ‘black-red’ coalition would become highly unlikely.

By contrast, the ‘Jamaica’ coalition has gained significant traction in the weeks leading up to the elections. Free Democrat leader Christian Lindner and Green co-chairs Katrin Göring-Eckardt and Cem Özdemir are largely expected to become highly sought-after kingmakers in the aftermath of Sunday’s elections, as both parties vie for third-place in the electoral race. The programmes of the CDU/CSU and FDP are usually assumed to be compatible, although some marked differences remain (in particular as regards Eurozone reform). FDP Leader Christian Lindner clearly opposes deeper fiscal integration and burden-sharing, strives for tougher fiscal rules, and would like to see Greece ousted from the Eurozone. These views stand in stark contrast with Ms. Merkel’s, who reticently shared her favourable opinion of French President Emmanuel Macron’s plans for further cross-border integration, which include the adoption of a common Eurozone budget. Nevertheless, it should not be omitted that the successes of Ms. Merkel’s second government (2009-2013) were based on a ‘black-yellow’ alliance with the FDP, thus granting legitimacy to the renewal of such a coalition in the near future.

Nevertheless, the ‘black-yellow’ coalition may not suffice to secure a majority of seats in the Bundestag (for now it is predicted to only garner 49% of seats) – at which point, most expect Ms. Merkel to consider the ‘black-yellow-green’ or ‘Jamaica’ coalition, which would add the Greens to the mix. However, the Christian Democrats seem less easily compatible with the Greens. Differing perspectives on asylum and dual citizenship law, as well as the conservatives’ traditional ties to the automotive industry remain thorny issues. Furthermore, and contrary to the ‘black-yellow’ coalition, Greens-CSU/CDU coalitions have only been witnessed in two of Germany’s Länder (including Schleswig-Holstein since its May 2017 state elections). Nevertheless, Merkel herself has hinted at the desirability of the ‘Jamaica’ coalition in interviews, declaring that “the humane shaping of globalization could be very exciting for the Green Party too.” Christian Democrats might also see a strategic advantage to the ‘Jamaica’ coalition, in that the Greens would offer a balancing act against the brash FDP leader, Christian Lindner, and thus bring stability to the alliance. From the Greens’ perspective, returning to government after 12 years in opposition may also be too tempting an offer to resist.

Instrumentalization, fragmentation, and the rise of illiberal discourse. Coalition-building seems inevitable, as much as its manifold implications for German politics. The implications of the two coalition-building options (‘black-red’ and ‘Jamaica’), though similar, would be amplified if the CSU-CDU forges an unprecedented three-way coalition. In the short-run, one could be fooled into singing the praises of such pragmatism; in the long-run however, its implications should not be dismissed. The long-run implications of pragmatic centrism and coalition-building in Germany are threefold: first, the instrumentalization (as opposed to the institutionalization) of party politics will result in the further fragmentation of the German political landscape. Second, pragmatism and coalition-building will continue to eat away at the quality of German democracy. Third and last, such processes will only provide more and more room for illiberal political contestation in the margins.

First, Ms. Merkel’s pragmatic centrism and coalition-building with, as well as asymmetric demobilization (weakening the opposition’s support-base through the appropriation of those opponents’ platform promises that remain palatable to the majority of one’s party base) of the opposition has and will continue to allow for the instrumentalization of party politics (as opposed to their institutionalization) in Germany. While institutionalized parties – first defined by Samuel Huntington by their autonomy, meaningful coherence, organizational stability, and rootedness in society – best articulate and aggregate interests, and as such, consolidate liberal and substantive democracy, instrumentalized political parties work towards politicians’ strategic manoeuvering rather interest-representation.

There is no denying that fuzzy congestion of the political centre in Germany is bound to damage the substantive and ideological grounding of mainstream political parties. Indeed, the asymmetric demobilization of the opposition does not merely hurt the prospect of a viable centrist alternative to the domineering CDU/CSU. It also threatens to disconnect the CDU/CSU leadership from its more conservative members, as well as to ultimately debase the party from parts of its electorate – let us here be reminded of the right-wing demonstrators shouting “Merkel must go” in Dresden last year. And immigration is not the only subject for internal dissent: for the party’s conservatives, Merkel has swung too far left on key issues such as the ending of conscription in 2011 and her relative openness to gay marriage legalization in June 2017. All in all, nothing illustrates the growing meaninglessness of German party politics better than the sheer illegibility of the #fedidwgugl hashtag, short for Merkel’s bland electoral slogan “Für ein Deutschland, in dem wir gut und gerne leben”(“For a Germany in which we live well and feel good”).

Second, many fear that pragmatism and coalition-building relentlessly eat away at the quality of German democracy. The 2017 electoral campaign has indeed been rather uneventful, to the point that conflict seems to have been deliberately avoided in the single television debate opposing Angela Merkel to Martin Schulz. The prospect of a future collaboration seems to have killed all meaningful debate. The candidates are “trapped in a vicious circle of compromises,” wrote the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Indeed, controversial issues have been significantly played down in Ms. Merkel ‘softly-softly’ campaign, which has clearly put a damper on the lively and challenging debate one would expect in the German liberal democratic setting. The instrumentalization of political parties, by reducing prospects for a viable alternative to the establishment, has also rendered healthy opposition and regular alternation of power unlikely.

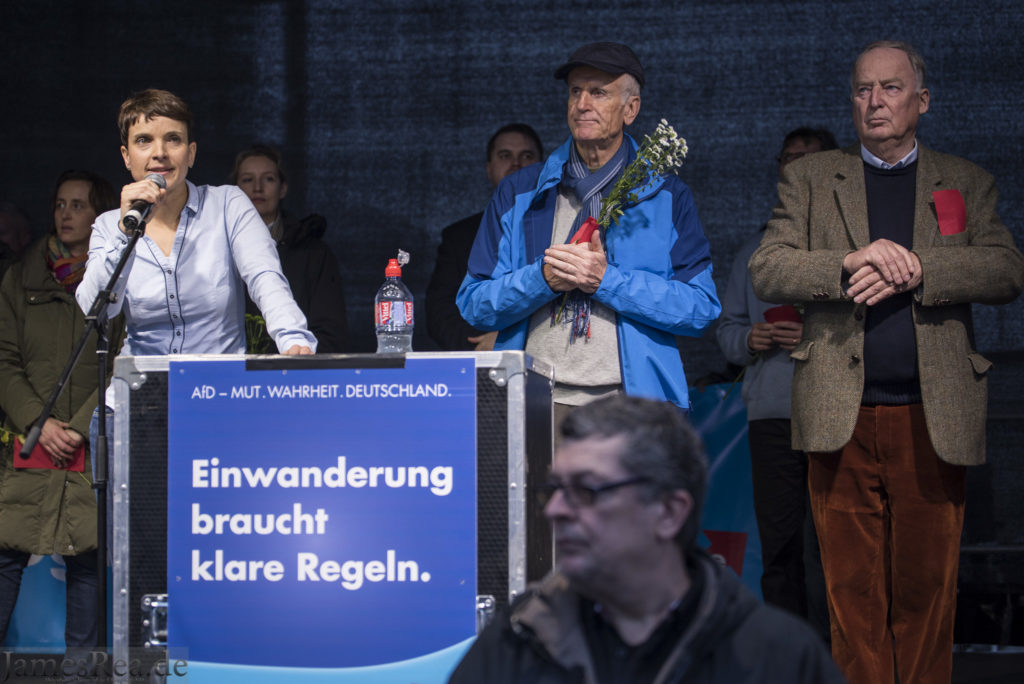

Third and last, the instrumentalization of German party politics has provided room for growing illiberal contestation in the margins. While the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats together held over 90% of the votes in the 1970s, they are predicted to only account for about 60% of the vote next Sunday – significant parts of the German electorate have shifted to the margins. Unsurprisingly, the Alternative for Germany (AfD), a right-wing, anti-immigration, anti-Islam, and nationalist party is expected to win at least 50 of about 630 Bundestag seats, and is most popular in the former East Germany, where voters would rather the federal government bridge the remaining post-reunification gaps rather than integrate refugees. It should be noted that fears of an Austrian-like collapse of the political centre and right-wing surge may be exaggerated – aversion to radical politics remains strong in Germany, where more voters consider themselves centrists (80%) than in any of the other major EU Member States. Nevertheless, the venom of illiberalism – the AfD has repeatedly called for a ban on minarets and burqa, arguing Islam is fundamentally incompatible with the German constitution – could dangerously take root in a post-industrial Germany faced with numerous crises (immigration and Eurozone governance, among others) and an overcrowded political centre.

Against German self-complacency. The instrumentalization and fragmentation of the German political landscape may still be in its early stages. Nevertheless, one should not neglect the destructive implications of pragmatic centrism and coalition-building in the long-term. As tempting as it may be, uniformly painting the German elections as an easy win for liberal and progressive values only dismisses the complexity of the puzzle at hand. The long-term implications of coalition-building for political parties’ institutionalization, as well as for the quality and liberalism of democracy, are not without precedent, as the Austrian case illustrates. The myth of German exceptionalism and its loyal adjuvants, elite pragmatism, and self-complacency, will only do so much.