Forgetting Ferdinand Marcos: The Dangers of Historical Revisionism

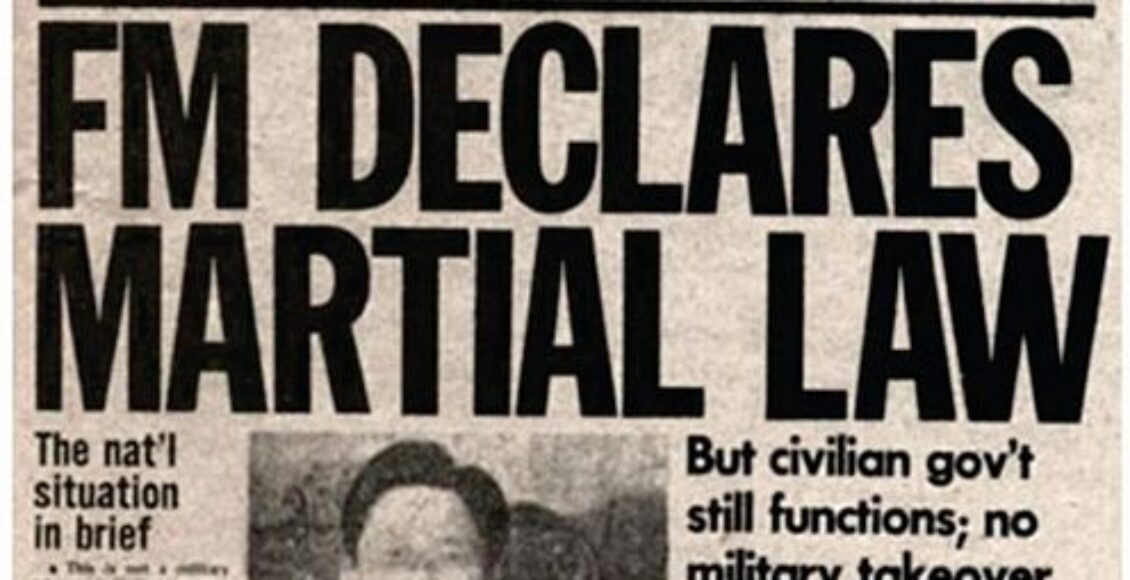

As the end of Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency looms large, campaigning for the next Philippine executive is well under way. Among the candidates is Bongbong Marcos (BBM), son of former president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Though the senior Marcos was democratically elected in 1965 and 1969, he extended his tenure by imposing martial law in 1972, initiating a personalistic dictatorship that became infamous for its unabashed corruption and widespread human rights violations. According to historian Alfred McCoy, an estimated 3,257 were killed, about 35,000 tortured, and roughly 70,000 arrested.

Despite the gruesome realities of the dictatorship, however, revisionist narratives of the Marcos era have emerged and gained traction amongst the Filipino populace. Utilizing their extensive funds, resources, and networks to promote “the glamour and high-profile achievements of the Marcos years,” the family has strategically and deliberately worked towards altering the collective memory of the dictatorship to facilitate a return to power. This historical revisionism romanticizes the Marcos era despite its adverse effects on the country’s human rights, politics, and economy. It frames the People Power Revolution as a coup against Marcos orchestrated by Corazon Aquino, who, in reality, legitimately defeated Marcos in the 1986 snap election. It suggests that propaganda distorts the legacy of Marcos, blatantly obfuscating the truth that abuses of power and human rights characterized the dictatorship. Apologists will also claim that no evidence exists to prove the dictator’s corruption and that the country’s economy prospered throughout his tenure.

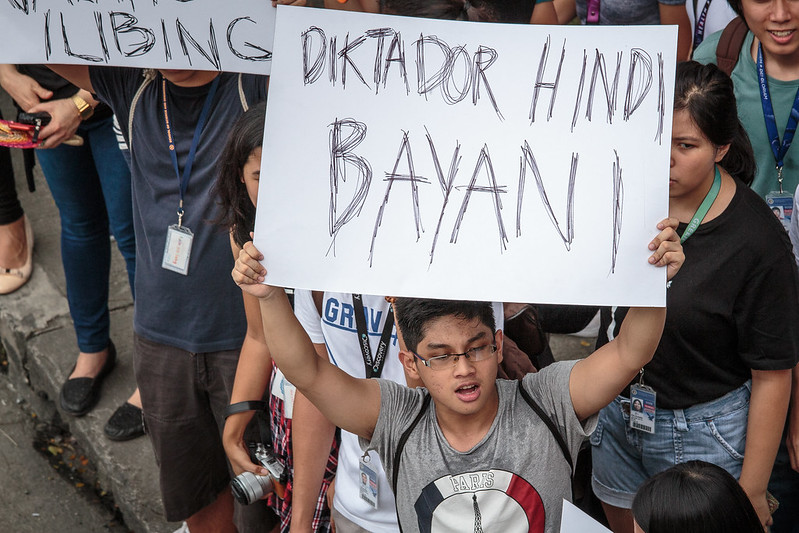

Moreover, they maintain a twisted nostalgia for the law and order that his ruthless repression of dissenters engendered. As McGill University professor Erik Kuhonta notes, the Filipino people have a clear desire for order and a leader who can provide it, exemplified by President Duterte. For his part, BBM describes his parents as “generous philanthropists” who innovated new varieties of rice and developed important infrastructure during what he and his apologists claim was the Philippines’ “Golden Age.” He similarly refuses to acknowledge the atrocities committed during his father’s reign. Meanwhile, the influence of this revisionism has permeated to the Philippine Supreme Court who, in their ruling that permitted Marcos’s burial in the country’s Hero’s Cemetery, described his human rights violations and corruption as “alleged.”

Though revisionist efforts began in traditional sources such as TV, newspapers, and books, they have permeated the digital space, primarily Facebook and YouTube, platforms that reach 45 per cent of the Philippine populace. With nearly all Filipino internet users having Facebook accounts and one in four consuming their news from the social media site (second only to TV), internet troll farms supporting both President Duterte and the Marcoses can easily reach audiences and promote false narratives. Moreover, a recent BBM interview on YouTube has enjoyed an overwhelmingly supportive comments section, despite being characterized by the Ateneo Martial Law Museum as a blatant attempt at historical revisionism.

Regardless of the convictions of Marcos apologists, their claims and memory of the dictatorship have consistently been disproven. Multiple courts, including the Supreme Courts of both the Philippines and Switzerland, have ruled that the Marcoses stole from the Philippines through fraud and graft. The Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), created by Corazon Aquino in 1986 to repatriate the assets and wealth stolen by the Marcoses and their lackeys, relatives and friends, such as Jose Yao Campos and Antonio Floirendo, Sr., estimated the value of embezzlement anywhere between P253 billion to P506 billion over the course of Marcos’s presidency. However, as of the end of 2020, the PCGG had recovered only P174.2 billion of the stolen gains. Furthermore, although the country’s economy had shown signs of growth in the initial years of the Marcos era, his crony capitalism facilitated corruption and protected inefficient conglomerates headed by the dictator’s friends and family. By the final years of the Marcos dictatorship, GDP growth had become negative, and the Philippines became considered the “Sick Man of Asia.”

Notwithstanding the ease with which critics have refuted the claims of Marcos revisionism, it has remained resilient and prevalent. Relatives and former lackeys retain key political positions, particularly in Marcos’s home province of Ilocos Norte, enabling the propagation of “alternative facts” to constituencies around the country. Moreover, the former dictator retains support from both citizens who benefited from martial law as well as young people who never lived through the terrors that typified Marcos’s reign. In turn, these apologists reconcile the inconsistencies between their beliefs and verified history through the “plasticity” of their memory that constantly adapts to fit whatever narrative is most amenable to their position.

The failures of the elite democracy that returned in 1986, such as unsuccessfully addressing ongoing corruption and inequality, have nurtured disillusionment amongst the populace that lends itself towards a more sympathetic view of the Marcos era. Although the country’s economy had improved under former president Benigno Aquino III, son of Marcos’s successor Corazon Aquino, Philippine society did not perceive this growth as equitable. Moreover, as a member of the traditional elite, Aquino’s inability to overcome these perceptions aggravated the public’s disappointment with the restoration of democracy following the People Power Revolution. The incumbent’s positive view of the former dictator has similarly encouraged and assisted the acceptance of “alternative facts.” Consequently, people are willing to leave the Marcos era in the past and accept a revisionist view of history that offers more comfort and pride. As noted by Lisandro Claudio, professor at Kyoto University, Marcos revisionism has resonated with Filipinos because they don’t feel “respected in the world anymore. They feel they are globally insignificant.”

Given the prominence of these sentiments amongst the Filipino populace, the dangers of Marcos revisionism are clear. Although the vice-president and president are elected separately in the Philippines, the BBM-Sara Duterte ticket nonetheless raises severe concerns about the potential future of Philippine democracy. A skewed memory of the dictatorship not only raises the possibility of this tandem assuming power; it could likewise create a precedent of forgetting atrocities that would enable future generations to forget the human rights abuses and attacks on rule of law that have occurred throughout President Duterte’s drug war and presidency. As Imelda Marcos understands, “perception is real and the truth is not.” In turn, Imelda’s perspective, and, by extension, Marcos revisionism, embodies the Thomas theorem: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” In other words, how we frame and approach a situation creates real, tangible effects. By crafting and propagating a new narrative of the Marcos dictatorship, the family and their apologists have the opportunity to rewrite history and usher in a new era of crony capitalism and abuses of power. Whether it be by forcing apologists to take their beliefs to their logical ends to prove their groundlessness or by finally addressing the societal problems that foster the willingness to accept “alternative facts,” it is clear that refuting Marcos revisionism is essential to protect and sustain Philippine democracy. By permitting these false narratives to fester and swell even further, the country runs the risk of repeating its history and relapsing into another era of authoritarianism.

Featured Image: “FM Declares Martial Law” by the Philippines Daily Express is in the public domain.

Edited by Emily Jones