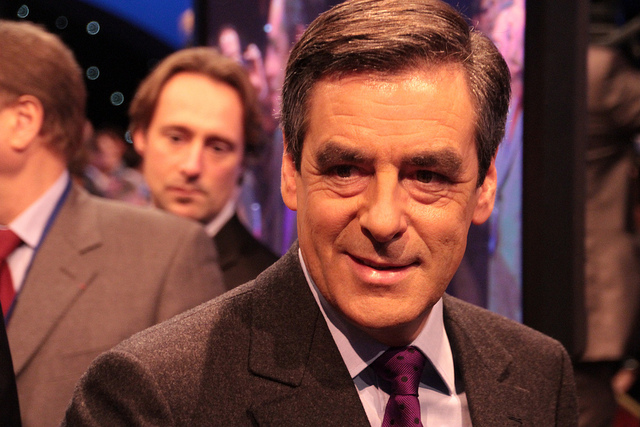

François Fillon: Another Le Pen? Another Trump? Hardly.

Last November the entire political scene was left absolutely stunned as the electorate made itself heard and revealed itself to be more welcoming of strident right-wing policies than polls had been showing beforehand. François Fillon came out of nowhere to largely defeat his rivals in the French conservative primary, dispatching Alain Juppé, the centrist and front-runner, by over 30 points in the runoff.

This came mere weeks after Donald Trump’s own surprise victory, and naturally some commentators sought to connect the two phenomena, painting Fillon as just another Trump, who “mainstream[ed] a far-right platform in yet another of the world’s nuclear powers” (a reference to the UK’s Brexit vote in addition to Trump), no better than nationalist French candidate Marine Le Pen.

This is fundamentally a misread of Fillon’s programme, which is radical but not dangerous or populist, and of the reasons for his appeal. Putting him on the same level as Le Pen and Trump is not just wrong but also reckless, considering the reputation that already exists in some circles of “liberal elites” screaming “racist” at anyone who disagrees with them.

Fillon’s victory was the result of a very late post-debate surge. Until the first debate, polls consistently had him in fourth place in the primary. Therefore, examining his performance in the debates, and looking at which issues he emphasized more or less than the other candidates is a good way of understanding why French voters decided to abandon their original candidates and instead, back him en masse. This exercise reveals clearly that it was what he called his “extremely precise project” for the economy, and not identity or security issues, that is the main component of Fillonisme.

“Extremely precise” is indeed a reasonably accurate description for his programme. He would get rid of France’s 35-hour workweek, including in the public sector, a move that would allow him to slash 500,000 government jobs. Labour laws would be liberalized, the retirement age would rise to 65, social insurance charges would be reduced to boost investment (compensated by a rise in the sales tax), welfare benefits would be merged, and further savings would result from reducing the number of parliamentarians and simplifying France’s millefeuille administrative structure. The ultimate goal is €100 billion less in government spending, which would leave public spending at around 50% of GDP, still higher than in the vast majority of developed countries. This is why the frequent comparisons between Fillon and Margaret Thatcher, while appreciated by Fillon himself, can be slightly exaggerated.

These measures are intended to boost an economy where unemployment has remained above 10% since 2012. Additionally, economic growth remains sluggish and government debt is approaching 100% of GDP despite significant rates of taxation. The reasoning goes that Germany and other northern European countries have already undertaken these sorts of reforms and consequently have healthier economies that can still sustain generous welfare states.

In other words, Fillon is not blaming some feeling of France’s “decline” on foreigners or Brussels, but rather on a peculiar configuration of French policies and institutions that could be fixed through economic policy, and his record, come re-election time, can be judged according to objective, numerical analysis. No part of the above sentence is true of Trump, or consistent with any form of populism. Not only is that not problematic, but it might even be actively good because clearly the sense of decline and insecurity is already out there among the French public and, before Fillon’s constructive policies, had only Le Pen’s angry and identity-based candidacy to turn to. Fillon’s presence has a possibility of taking away votes from her this election, but also if his economic shock therapy bears fruit, reducing the need for a right-nationalist party of grievance in the future.

Another major indicator of far-right populism are one’s views on Europe. The idea of “taking back control” from some corrupt elite (most caricaturally phrased as “draining the swamp”) is the bread and butter of populist rhetoric, which is why all “far-right” parties have also been Eurosceptic. This rhetoric is missing entirely from Fillon’s discourse, and not because the debates didn’t offer a platform for such issues (they allowed primary candidate Jean-Frédéric Poisson to make his views on the EU very clear), but simply because Fillon largely believes what many conservatives across the continent do: that Europe needs a few tweaks, especially in its economic powers, but that neither a federalist leap nor a Le Pen-style “Frexit” are good ideas.

Another aspect of “far-right” groups is crafting a strongman image who maintains law and order and punishes deviants – an especially emotive debate in France following the terrorist attacks of Paris and Nice. There were plenty of conservative candidates who responded to this need. Bruno Le Maire and former President Nicolas Sarkozy, both of whom spent most of the campaign ahead of Fillon in the polls, spoke extensively and menacingly of the need to preserve French identity and democracy from the encroachments of “political Islam.” Former party chairman Jean-François Copé made the massive and immediate hire of 50,000 more security officials the centrepiece of his campaign, arguably the only memorable thing he said. All three, to varying degrees, supported the establishment of a parallel judicial system for suspected terrorists. Subsequently, all three lost to the man who defended his decision, as Prime Minister, to fire 10,000 security officials as part of post-recession budget-cutting.

To be clear, Fillon did also publish a book just before the campaign titled Vanquishing Islamic Totalitarianism and, in the final debate, rejected multiculturalism as a model for France (immigrants are welcome, he said, but should assimilate). But these positions were, again, hardly the most radical in the primary (and certainly don’t resemble populist cries of “the country’s full” or “immigrants are taking natives’ jobs”), and so wouldn’t explain why so many voters switched to him from other candidates. He also did not focus on this issue nearly as much as other candidates did, or as he did his economic plan – in addition to watching the debates, glancing at Fillon’s and Le Pen’s platforms illustrate how differently they prioritize issues.

Then, there is his very Catholic-informed worldview that some have seized upon as evidence of reactionary conservatism. This ignores the fact that, as he has carefully pointed out, those personal beliefs do not mean he would roll back homosexual couples’ right to marry and adopt children, or women’s right to abortion. To some, the very fact that he and his worldview appeal to some of the same social-conservative, nationalistic citizens as Le Pen is a crime in itself, as if those citizens do not deserve to feel represented in a democracy such as France. No, what does matter is the content of the actual policies on offer, and here too, Fillon, who largely separates personal beliefs from political platform, is hardly “far right”.

This article is not an endorsement. To say that his programme is not dangerous is not to say that it’s the best one on offer. (The independent candidate Emmanuel Macron, for example, seems to be better at balancing the need for economic reform with an attention toward social justice, though he is yet to publish a comprehensive platform.) Rather, this is a call for calm. Fillon is not “mainstreaming a far-right platform”, but is rather a typical conservative politician who carefully constructed a platform, full of concrete proposals, within the realm of standard ideological disagreement. If he wins, after his presidential term, the French economy would likely look different (and, with any luck, better), but French democracy would continue to be conducted with more or less the same procedures as before – something that sadly cannot be said of Trump’s America or Brexit Britain.

The most likely scenario is that the runoff round pits Fillon against actually xenophobic, anti-Brussels wall-builder Marine Le Pen. They are not two sides of the same coin. The choice should be obvious.