From Assimilation to Acceptance

A journey of self-acceptance in discovering my bi-cultural identity.

“Where are you from?”

Growing up and looking around me, this seemed to be a simple question for most. My classmates would answer quickly “Canada.” Young, naïve and determined to fit in, I went along with it.

“I’m Canadian.”

“But where are you really from?”

And that’s when things get difficult.

When faced with the challenge of figuring out who you are, society nor the state has made it easy for a second-generation immigrant. Whether it’s the state you were born and raised in or the ancestral home determining your ethnic heritage, claims to either are quickly dismissed.

Originally, my family hails from India – specifically, the northern state of Punjab. Both my mother and father as well as their parent were born there, but ultimately settled in Canada. Which led to me. I was born here – on a presumably sunny July morning in Montréal’s Jewish General Hospital as the first Canadian in the family.

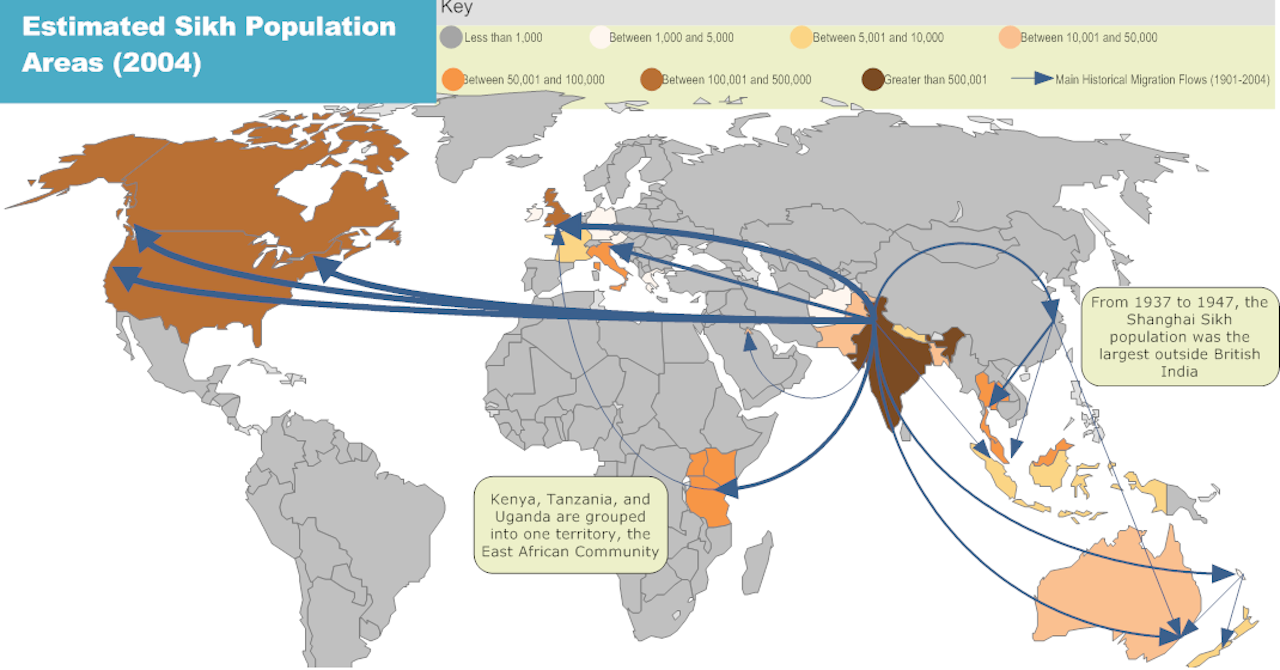

Yet, while growing up, the question of who I am and where I belong became increasingly tiring. I was told we are Sikh Punjabis, from the numerically minority ‘Saini’ caste. A small community in comparison to other castes, we’re known as landowners and farmers descending from Rajput warriors who took up agriculture in the face of Mughal conquerors. Labels had been thrown at me from all different directions. Indian. Punjabi. Sikh. Saini. Canadian. Immigrant.

“Who am I?”

My first qualm was with the word immigrant. Immigrant is defined as “a person who comes to live permanently in a foreign country.” Statistics Canada defines each generation as either first, second or third. First generation immigrants are posited as foreign born, naturalized citizens whereas second gens are defined as those “born in Canada [with] at least one parent born outside [the state].”

I’d find myself contemplating; ‘If an immigrant is someone who hails as a foreigner, are we not all foreigners compared to the indigenous communities that originally hail from Canada? What makes me so different from the others?’

My thoughts were swiftly silenced as I observed my peers and attempted to fit in. Although multiculturalism is celebrated in Canada, I knew the more I hid my identity the better off I’d be. The more “normal” I’d seem. Diwali celebrations and cultural education at my elementary school meant nothing to me. PB & J sandwiches and orange slices after soccer practice solidified my status as an ordinary kid in the BC Lower Mainland.

Still, I knew in their eyes I would always be the “other.” An idea that cemented in my mind when my teachers advised shortening my name on resumés and applications. “Dil is easier” than Dildeep Kaur. More doors would open for me. More opportunities. A modern-day version of assimilation. A rejection of not just my ancestral culture and heritage, but even my name.

“Why are you so white?”

My mother would ask me. My siblings were not as hostile as I was towards our culture, religion and heritage. I on the other hand, continued to erase any markings of my ancestry hoping it would work. Hoping to fit in.

Fast-forward to 2008. My first memorable trip to India at the age of eleven. Having visited once prior at the age of four, I really wasn’t sure what I was in for.

What I really didn’t expect was children yelling “Foreigners! Foreigners!” while running alongside the car my uncle had picked us up in. In India, everyone immediately labelled us as Canadian. Not just me, the aforementioned “white” one of the family but my sisters and mother too.

Envious at our impeccable English and social freedoms my cousins aspired to escape as my parents had. The longer we stayed the more I understood. As girls, we weren’t allowed to leave the house alone. Not even to the end of the block to buy sweets. Yet, I didn’t like being told I had an accent when I spoke in my mother tongue. Nor did I appreciate the gaggle of men staring at our foreign attire and fair skin. But after rejecting all aspects of my heritage, what else should I have expected?

Colonial legacies run rampant throughout India. Fair skin is coveted, and foreigners admired. Being treated as a foreigner isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But for me, it just meant more confusion surrounding my identity. On top of that, India is one of many countries that don’t allow dual citizenship. For many Indians, those who leave and relinquish their right to an Indian passport are foreigners. Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) is a term commonly thrown around to define those who work out of the state but remain Indian citizens. Even in this category I couldn’t find any claims to who I was.

So, here I am. Sipping my chai, blasting music on my iPod, trying to figure out who I am supposed to be.

In Canada, it was obvious I was seen as the other. Someone who visibly did not belong despite internally assimilating to the ‘ordinary’ way of life.

And in India, I was seen as an outsider. Someone with little claim to the culture and tradition they all held so dearly.

The rejection I felt from each end of my identity continued to grow inside me. And I continued to ignore it.

“I am me.”

That is, until college. Wide-eyed and books in hand, I was eager to learn. What I didn’t realize was alongside higher education, I’d be learning a lot more about myself. It was only at McGill where I looked around me and realized there can be harmony and duality within cultures and claims to identity. All around me I saw a variety of combinations which motivated me to take what was mine and use it to create who I am. Who I really wanted to be.

What I finally realized, was the value of my dual-identity that I had forever seen as a disadvantage. This disadvantage, although relevant in Canadian society, had been ultimately embellished in my own mind. On one hand, I had this beautiful and elaborate culture, tradition and history to enjoy throughout my life. And on the other hand, I had the social superiority and opportunity of someone living without labels and markers determining who I am.

Evidently, in a caste-class-gender-religion dominated social system such as that of India, I could have easily been silenced. I’d have little rights in a state dominated by Hindu males in social and political settings. In a nation of 1.2 billion people, there are six census recognized religions yet 79.80% of the population is Hindu leaving the minorities to fend for themselves. This is not relatively new. India has engaged in the maltreatment of minorities for ages.

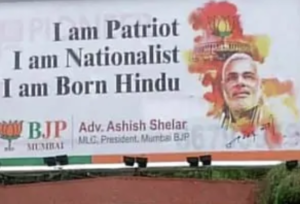

The very idea of the Partition itself is an example. Alongside Post-Partition struggles leading to massacres of Sikhs and Muslims across Punjab, there’s numerous instances of marginalization. Despite the clear prohibition of discrimination enshrined in the Indian constitution, Hindu nationalism has reached new heights in claiming cultural superiority. Currently, the reigning BJP government is asserting Hindu dominance by challenging multicultural narratives. By claiming modern day Hindus descend from the first inhabitants of India, the BJP is rewriting the national identity of India and ignoring a large portion of the nation’s history and people.

Castes result in further segregation and abuse. The caste system arose in ancient India to determine familial obligations. Some families were levelled as priests or holy figures, others as military affiliates, some tradesmen and so on. At the time, the system made sense in aiding population control and maintenance of society. But with modernity on the rise, and new careers in the mix caste classification is shifting. Laws against caste discrimination as well as affirmative action laws for low-caste government positions have been implemented. Despite that, castes are resilient and remain difficult to abolish. Simply someone’s last name determines their place in society. To this day, inter-caste marriages although publicly encouraged can result in murders and honour killings. The caste system in India remains prevalent and problematic with no solution visible in the near future.

But with my Canadian passport in hand, alongside the opportunities I had growing up, I have the ability and power to challenge these notions and take a stance. Indian society sees foreigners as beyond their categorizations, a legacy still in place after 200 years of British colonization. From skin-lightening fairness creams to foreign policy legislation, colonial legacies are alive and continue to thrive in modern day India. As a result, an obsession with foreign citizenship and NRIs breaks past the domestic classifications in India.

Foreigners are inherently seen as superior. Due to this superiority, voices that would commonly be dismissed refuse to be silenced. For example, a female, Saini Sikh Punjabi born, raised and living in India would be commonly ignored in pursuits of social activism. But as an Indo-Canadian woman with minority background claims I can use those facets to my advantage. The awareness that comes with my ancestral background and the power present in my national identity results in my refusal to be silenced. It allows me to pursue a platform against maltreatment of minorities with internal knowledge of the situation and external advantages of heightened social status.

I am above the classifications of Indian society and I am beyond the legal labeling in census Canada, because

I am both.

I am Indo-Canadian. And proud.

Edited by Sarie Khalid