From Bad to Worse: Reproductive Rights in America

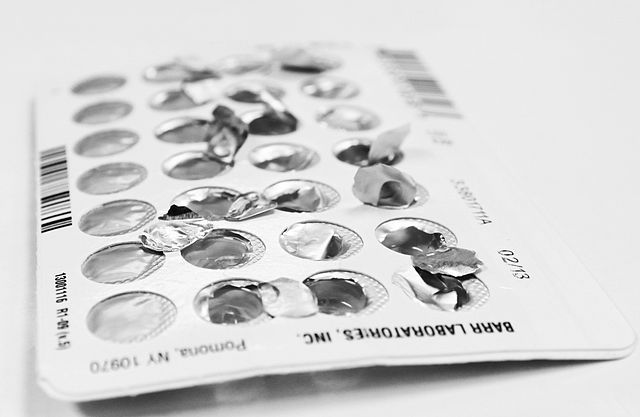

Despite accusations of sexual assault by several women and a historic in-court testimony from one of the accusers, President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee was confirmed on October 6th. The hearings for Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation have been unspeakably draining in their own right for survivors everywhere. To make things worse, Kavanaugh’s accession to the Supreme Court could spell significant danger to reproductive rights in America. As a conservative judge, Kavanaugh’s nomination has left many anti-choice groups like Texas Right to life excited for “the beginning of the end for Roe V. Wade,” the landmark Supreme Court ruling that made banning abortion unconstitutional. At one of the confirmation hearings, Kavanaugh even incorrectly referred to birth control pills as abortion-inducing.

In the days and weeks prior to Kavanaugh’s confirmation, many reproductive rights activists sounded the alarm over the risks posed by Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court. “If Kavanaugh is [selected for] the Supreme Court – Roe v. Wade is absolutely at risk,” says Ohio-based abortion rights activist, Mason Hickman, whom MIR interviewed. Even before Kavanaugh had been confirmed, Hickman said we had “every reason to be called to action right now.” Hickman is the Communications and Digital Media intern at Planned Parenthood Votes Ohio, the Sexual Education chair for the Planned Parenthood student group at Ohio State, and is also a volunteer clinic escort at a Planned Parenthood surgical center in Columbus, Ohio. He has been involved in reproductive rights advocacy in Ohio for three years and is also a recipient of their services.

Kavanaugh’s stance on reproductive rights and his future work on the Supreme Court aside, the state of reproductive rights in the United States is already dire, especially in states that typically vote Republican. In fact, access to reproductive care has deteriorated in recent years. Between 2010 and 2016, states passed 338 new abortion restrictions. These 338 new restrictions account for nearly 30% of the 1,142 abortion restrictions enacted by states since the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade. Currently, five U.S. States are down to only one abortion clinic: Missouri, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

The more conservative states in America are not the only ones that have restricted access to abortion. In recent years, even in states known for being moderate, such as Ohio, the far right has been able to dominate the political conversation on reproductive health-care. This has had significant ramifications for the rhetoric and ultimate policy surrounding reproductive rights within the state.

“We have had John Kasich as our governor since 2010,” says Hickman, suggesting the impact of long-term Republicanism on reproductive rights. “Under Roe v. Wade in America, states are allowed to implement further restrictions on abortion services as they see fit as long as they are not causing an ‘undue burden’ to the patient – undue burden is vaguely defined. Since taking office, [Kasich] has signed nearly 20 anti-abortion measures into law. So, while abortion is still legal statewide – obtaining one is [increasingly] difficult.”

One such anti-abortion restriction in effect in Ohio is the 24-hour consent law, which requires patients to wait a full day after meeting with a licensed physician before receiving an abortion. “[This law] creates a huge barrier for low-income individuals trying to access services who may not have the resources needed for this. The 24-hour mandatory waiting period does not consider that many patients are traveling from hundreds of miles away, may not have childcare during this time, may not be able to afford lodging while they wait for the procedure, and may not be able to take time off work for more than a day. With all of these costs considered, it is important to remember the patient is also paying for the abortion – so we’re talking hundreds of dollars already. Due to this, accessing and receiving an abortion could cost well over a thousand dollars once you arrive home. This is not a possibility for many low-income individuals who still deserve access to services,” explains Hickman.

Another such issue in the state of Ohio, and many other states, is that government funding for reproductive healthcare is not always allocated to clinics that prioritize legitimate reproductive healthcare. Rather, the money often goes towards funding places like so-called “Crisis Pregnancy Centers”(CPCs), which typically refuse to offer information to patients regarding abortion services.

“Crisis Pregnancy Centers are dangerous because they are not licensed to provide medical services,” says Hickman. “They give the appearance of a medical facility, but their main goal is to attack patients with anti-abortion and anti-choice rhetoric. They have been known to withhold medical information from patients, which is incredibly harmful and misleading. The best way to help people protect their health is to give them the tools they need to make responsible choices for themselves, and CPC’s do not do that.”

Because many of these centers are placed close to actual Planned Parenthood Clinics and have similar sounding names, many people risk going to them believing that they will be able to access STI testing, birth control, or an abortion. Instead, these clinics are often deceptive. In one academic study, researchers posed as persons needing reproductive healthcare, and called over 100 crisis pregnancy centers and visited fifty-five centers in the state of Ohio. They found that CPCs were consistently misleading in what they told prospective and in-person visitors. In their phone calls, sixty percent of CPCs did not specify that they were not medical facilities. Although all CPCs during the study called were asked about an abortion referral, only one offered the service. In person, the CPCs overestimated the risks of miscarriage or other adverse health effects an abortion patient could endure post-procedure. Moreover, when in-person researchers had a negative pregnancy test at the facilities, they were not provided contraceptive services. Instead, centre personnel often recommended abstinence only, or said that contraception was ineffective or even caused abortion.

Although CPCs do not provide the medical care their patients are often seeking, they still receive funding from the state of Ohio.

When asked about what else is often left out of the conversation on reproductive healthcare, Hickman explained that “when talking about reproductive justice, we constantly forget about the right to choose. While having access to abortion services is important, it is just as important that the people of Ohio have adequate resources for raising a child. This means supporting paid family leave, giving schools adequate funding, hav[ing] accessible public transportation and [creating] affordable housing. Having an abortion can only be liberating when it is a choice that someone makes – not a final resort because they do not have the resources to carry a wanted-pregnancy to term. Support people who want to carry a child to term and raise it just as much as you would someone who wants to get an abortion.”

Hickman also emphasizes the need to keep in contact with one’s representatives, and to vote. He also discussed other direct actions one can take to protect reproductive rights in Ohio and elsewhere: “If you support reproductive rights [and] you’re just as horrified for the future as the rest of us are – sign up to volunteer with a local pro-choice organization. Canvass with organizations so you can connect with voters and let them know what is on the line, [and] donate to these organizations so that they can continue their work.”

Conservatives hold significant power at the state level across the United States, even in “moderate” states such as Ohio. As such, they have been able to dominate both rhetoric and policy on reproductive healthcare. While Kavanaugh’s confirmation adds yet another layer to this issue, access to reproductive care has been at risk in America for a long time.

Edited by Catharina O’Donnell.