From British Myth to Canadian White Saviorism

Who were the ‘Black Loyalists’?

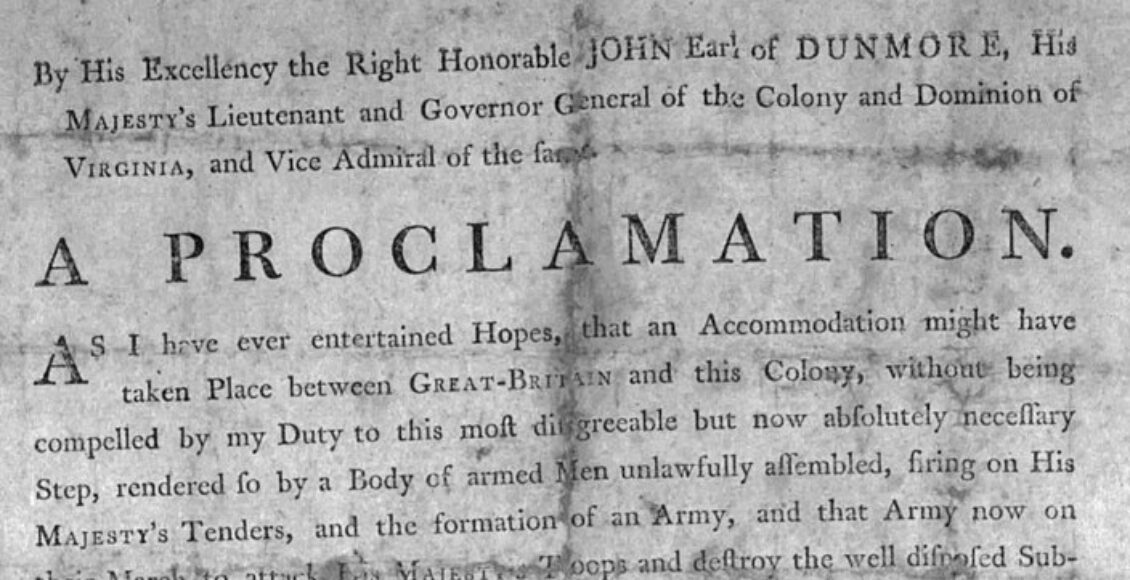

On June 30, 1779, General Henry Clinton issued his Philipsburg Proclamation, expanding on Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775 and promising freedom to all enslaved people who escaped from their Patriot enslavers to fight on the side of the British during the US Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Thousands of enslaved individuals fled their American enslavers throughout the Revolutionary War to seek freedom behind British lines, many to Canada. Those who did so were labelled as ‘Black Loyalists,’ remaining “loyal” to the British Crown. The term ‘Black Loyalists’ is a calculated label that falsely implies a positive relationship between them and White Loyalists while ignoring the independent motives and experiences of the Black Loyalists during the war. Seeking to establish themselves as abolitionists and morally superior to the US, the British claimed that their offer of emancipation was derived from pure intentions. History, on the other hand, suggests otherwise.

Loyal to freedom, not the Crown

Although Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775 was the first mass emancipation of enslaved peoples in history, Gary Nash, author of The Unknown American Revolution, argues it should be regarded as “an announcement of military strategy rather than a pronouncement of abolitionist principles.” Looking back, it is evident that British motives were not founded on the desire to respect human rights. In the proclamation, they were careful not to extend their offer of freedom to those enslaved by British Loyalists. Today, framing the experience of Black Loyalists as an act of loyalty to the Crown is belittling to their struggles and intellect. It is important to emphasize that these individuals were not blind to the ulterior motives of the British. The Black Loyalists held agency in their decision, sacrificing their community, wives, and even children for the promise of nominal freedom. The decision to fight on the side of the British was a strategic “alliance of convenience,” as the Crown was their enemy’s enemy, and thus their friend.

Why is this myth so dangerous?

Perpetuating ‘the Black Loyalists myth,’ as legal scholar Barry Cahill calls it, is dangerous “since the main constitutive element of the myth, loyalism, was not relevant to fugitive slaves.” This is not to claim that none of the free African Americans were Loyalists in their devotion to the Crown, but rather that the majority of those enslaved in America defected to the British in search of freedom and not in a show of loyalty to the benevolent Crown. This motivation is evidenced by the words “Liberty to Slaves,” inscribed on the uniforms of those who first joined Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment during the initial wave of emancipation. The title ‘Black Loyalists’ insinuates their similarity to White Loyalists, downplaying the inhumane experience of enslavement as a critical difference between the two; those who were Black had escaped, while those who were white continued to practice. As stated by Cahill, “one cannot right the wrongs of history by turning Black people into honorary whites, fugitive slaves into Loyalists. To do so is to permit the colonization of Black history by white historical myths.” Unfortunately, the colonization of Black history is as much of a part of Canada’s history as it is our present.

A Continual Pattern?

Since the Revolutionary War, Canada has declared independence from the British. Yet, it still maintains the same pattern of historical manipulation in upholding an image of moral superiority relative to the United States, whose involvement in creating and upholding the institution of slavery is undeniable. The British were largely successful in being seen as a champion of the anti-slavery movement, abolishing slavery before the US in 1833. As then colonies under the British Crown, Canadians “boast with an even more positive representation or the convenience of non-representation and thus the apparent lack of involvement,” writes Odgen, Perkins, and Donahue.

When enslavement is discussed in Canada, it is often conducted from a moral high ground, relying on the country’s role in the 1800s as a ‘safe haven’ for those seeking to escape enslavement in the US via the Underground Railroad. To this day, institutions clutch tightly to the myth that Canada’s ties to the practice of slavery begin and end with the Underground Railroad: “The story of the Underground Railroad is a positive moment in Canadian history, worthy of commemoration,” writes The Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

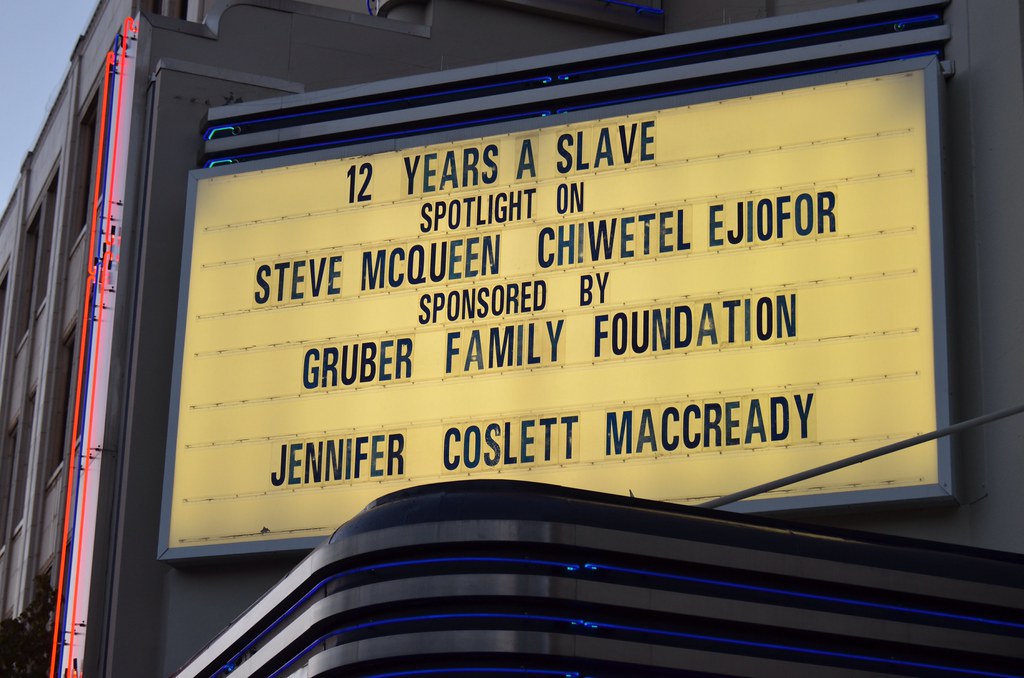

In all forms of media, the ‘good guy’ vs. ‘bad guy’ dichotomy is again drawn between the “anti-slavery Northern and the pro-slavery Southern US American,” according to Bernáth, author of Black Slavery in Canada. When Canadians appear in such media, they are often cast in the ‘white saviour’ role and so too by public perception. Films about the Underground Railroad feature Canadians as white abolitionists who help enslaved peoples escape, perpetuating the narrative of white Canadians as indispensable saviours that enslaved peoples must rely on to succeed. In Race to Freedom, Michael Riley plays Dr. Alexander Ross, a Canadian whose only characteristic is saving enslaved individuals. Similarly, in 12 Years a Slave, Brad Pitt plays Samuel Bass, a Canadian man who sacrifices his safety to help ‘free’ those enslaved.

The narratives in these works indicate a general perception on the part of Canada and its citizens that their role as abolitionists is absolute. However, this is only a fragment of the truth. Such fallacies permit favourable gaps, affording the Canadian government and its non-Black citizens the luxury of avoiding accountability for their direct participation in the enslavement of Africans. Just like the US, Canada too was founded on the backs of enslaved Africans. Beginning in the early 17th century, French colonial settlers in New France practiced chattel slavery, treating people as personal property that could be bought, sold, traded, and inherited. New France viewed the enslavement of African and Indigenous peoples as an instrument to fuel its colonial economic aspirations of mirroring the Caribbean’s institution of slavery. “The best way to remedy the situation would be to have Negro slaves,” wrote Jean-Baptiste Lagny to the French King Louis XIV in a formal request to import enslaved Africans due to a lack of economic progress at the time. The purchasing and selling of enslaved peoples were not only widely practiced by European settler colonialists in New France but were later codified within the law. On April 13, 1709, co-Intendant of New France Jacques Raudot solidified the legality of slavery, issuing an ordinance declaring, “all the Panis and Negroes who have been bought, and who shall be bought hereafter, shall be fully owned as property by those who have purchased them as their slaves.” This codification of slavery justified free labour and rationalized the deprivation of autonomy over a human being’s own actions, words, environment, and body, transferring absolute control to another (Code Noir 1685 and 1724). This right was preserved throughout the British occupation until 1834, when slavery was abolished in Canada.

Nevertheless, according to Black Canadians, this nominal freedom did not grant them equality overnight. Discrimination – legal, political, social, and economic – continues today. With knowledge of Canada’s fallacies and their detrimental effects, it is vital to actively work to deconstruct and then counteract them on all levels: state, provincial, and local. Acknowledging and understanding the implications of Canada’s pattern of colonizing Black Canadian history for personal gain and the perpetuation of a benevolent image is the very minimum required to begin reconciling and changing such harmful patterns.

Featured Image: Pictured: A copy of Dunmore’s Proclamation, issued November 7, 1775. Photo by Wes A Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Edited by: Grace Parish