George Washington, Gerrymandering, and the Galactic Senate

Over the past year, we at the McGill International Review have done our very best to give you insightful analysis about the world as it exists today, from repression and democracy in Hong Kong to the legacy of those “disappeared” by the Argentinean junta of the 1980s. We’ve covered everything from French laïcité to banking scandals, and from the Zika virus to Russian expansionism.

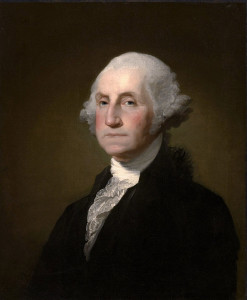

This article is not going to be anything like that. Rather, come with me as I explain to you what George Washington, the European Union, and the Galactic Senate from Star Wars can tell us about why the American political system is in seemingly-permanent deadlock. Bear with me.

In a farewell address that anyone who attended an American high school will no doubt be at least passingly familiar with and which was just recently featured in the Broadway hit Hamilton, George Washington, the first president of the United States, warned against political parties in strident terms:

“The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism… Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.”

If that sounds awfully familiar to you, it’s because you, like millions of other American voters, see a Congress so politically paralyzed that it is incapable of carrying out one of the things it is expressly ordered to do by the Constitution or, indeed, anything at all other than attempting to repeal a single law over fifty times. You, like George Washington, would be forgiven in concluding that it is the parties themselves that are the cause of this gridlock. If only there were no parties, the thinking goes, maybe Congress might actually get meaningful policy implemented. Our elected representatives would think about the issues of the day in substantive terms, make their own moral judgments, and ultimately act in the best interests of the country – what one might call the Mr. Smith Goes to Washington school of American political thought.

So what might a political order without political parties actually look like? Would you believe me if I said the Galactic Senate from Star Wars? Prior to its dissolution by the Galactic Empire, the Senate comprised the representatives of thousands of systems. Each of these had their own ecologies and systems of local government, ranging from elective-monarchist Disneyland to desert backwater to a planet that is literally one giant city. The interests of these individual planets alone could not possibly be more different, let alone the interests of the hundreds of species and droids that inhabit them. And yet, not a single political party or trans-planetary interest group to be found.

Star Wars canon has it that the Republic succumbed to corruption and fear, allowing the rise of the Empire. Really, it was corrupt from day one. Let’s consider why. Suppose you’re a newly-minted representative of a small rural constituency like, say, Iowa Dantooine. The Chancellor decides that he wants a few million credits for an infrastructure project in the Core Worlds. The problem is, he needs the votes of Senators from other parts of the Galaxy, as well – which is to say, your vote. You have no particular reason to vote the Chancellor’s way unless he sweetens the pot. Say, doesn’t Dantooine have a lot of bantha herders? Why not give those poor hardworking small businessmen a subsidy? The local economy has an uptick, you keep your seat in the next election, and just like that, a politics of quid-pro-quo is born. Porkbarrel spending is not a quirk of the system. It is the system. All you, Senator from Dantooine, have to concern yourself with, is your next reelection.

But surely the voters could vote you out once they see you’re corrupt, you say. Well, they could, but they won’t. You see, Senator, it’s only corruption when another constituency does it. The Senate may have a lower approval rating than your average communicable disease, but you’re One of the Good Guys, especially now that you have Big Bantha on your side, throwing millions of credits into inspiring re-election ads. Everyone from Alderaan to Yavin IV might think you’re corrupt, but they don’t get a vote, your constituents do, and in the absence of trans-planetary linkage mechanisms like political parties, there’s not really anyone who can keep you from office. In that sense, the Galactic Senate more closely resembles the real-world European Council, composed of the heads of state or government of the European Union’s constituent states, than the European Parliament, which is directly elected. The flaws of such a system are obvious, and contribute to criticisms of the EU as undemocratic. You may not like Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, but he has a seat on the Council just like everyone else because of how Hungarians voted, even if the manner in which he was elected was itself wildly undemocratic.

What’s worse, that’s the best case scenario. The redeeming quality of the Galactic Senate is that it is at least ambiguously parliamentary, meaning that the executive is inextricably bound to the legislature. If the Chancellor loses the support of the Senate, he can (and does) lose his position to a vote of no confidence. But suppose the executive isn’t bound to the legislature, as is the case in monarchies and presidential republics alike. The executive, being a vast network of resources and institutions centered behind a single individual, will find it all too easy to nudge, cajole, threaten, and bribe its way to invincible legislative majorities, reducing the legislature to nothing more than a rubber stamp. Don’t believe me? Ask Morocco. There’s a very good reason monarchies prefer fragmented parliaments whenever they can get them. There is also miles of distance between Barack Obama (or Hillary Clinton, or Ted Cruz) and King Mohamed VI of Morocco, but the art of writing and amending constitutions demands we take nothing for granted.

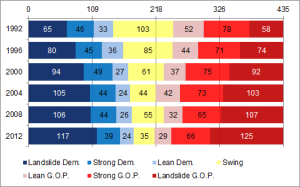

Which brings us back to the United States. This is all not to say that parties are a perfect mechanism: they aren’t. Parties can develop interests of their own, can gerrymander electoral districts in their favor, and establish local political fiefdoms like the one I just described above. In fact, in the United States, that is exactly what they have done – 38% of all US Congresspersons represent “safe” districts, that is to say districts that consistently elect the candidate from a single party. In a two-party system, it can be easy to see why; the parties do not compete, but cooperate. Each benefits from having the boogeyman of the other to rally the base behind, and neither benefits from actual legislative cooperation. Case in point: congressional Republicans have done nothing but obstruct Democratic proposals and have reaped win after win after win in the process. Because of how Americans elect their representatives, the two-party system is here to stay, thanks to something called Duverger’s Law. In layman’s terms: if there’s only one winner per district, and that winner is who gets the most votes, a two-party system will inevitably follow.

So is America damned if they do, damned if they don’t? Are Americans stuck with a political system either with parties and thus partisan deadlock, or a system without parties that undermines the purpose of the legislature itself? Not quite. Political parties may be inevitable, but a political system that does not take them into account isn’t. Voting systems based on proportional representation, for instance, get around the problem of gerrymandering either by compensating for district seats with at-large ones or by abolishing them altogether. But that means embracing political parties, not pretending like they’re going to go away.

Or, of course, we could just declare an Empire and be done with the lot of it. That always goes well, right?