Germany’s Refugee Lines and Trying Times

Syrian refugees waiting to be registered In Berlin, Germany (2015)

Syrian refugees waiting to be registered In Berlin, Germany (2015)

In the summer of 2015, German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced a historic and generous refugee policy allowing thousands of asylum seekers into Germany. It is a decision she continues to stand by strongly. However, Merkel cannot help but acknowledge the flaws in the policy, which have already led to losses for her political party, the Christian Democratic Union of Germany, in the 2016 State Elections in Berlin. Although policies such as the nuclear program shut-down and the lack of European Union (EU) structural reforms have stirred up controversy among local Germans and EU members, the Migrant Crisis has by far been the most disputed topic in contemporary European political discourse.

Asylum- and refugee-related policies have faced an array of problems since these problems gained importance. However, the Basic Law of the Republic of Germany (Article 16a) holds that any individual facing political oppression and persecution in their country has the right to seek asylum in Germany. Moreover, if asylum or refugee status is granted, the individual enjoys benefits similar to those of an ordinary citizen, including social insurance and child benefits. German immigration institutions are also designed to make integration and assimilation easier. For instance, language courses are offered and initial allowances are distributed to those with asylum status. According to the testimonies of Syrians now living in Germany, the process of assimilation was fairly manageable before 2015.

It is the scale on which Germany has attempted to absorb the refugees that has created both economic and social pressures, fuelling parties of the far-right in their rise up the political ranks. “We can do it!” has been Merkel’s stance on letting over a million refugees into Germany. Although her attitude epitomizes altruism and displays a commendable humanitarianism, it also stretches the limits of an increasingly skeptical society. In a speech on the 18th of September, Merkel acknowledged that the process of accommodating refugees could have been handled better. For example, the refugee screening and documentation process was conducted haphazardly. However, Merkel has stood her ground by not modifying the open borders policy. This decision has become increasingly unpopular since the series of attacks and violent incidents that struck Germany in July of this year, the most egregious of which involved a teenager of Afghan origin attacking people on a bus with an axe before being shot down by the police. However, reports that indicate crime rates amongst refugees are similar to the German average, and these reports have been published and especially circulated to reduce tensions.

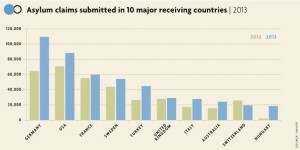

The social divide in Germany seems to be deepening at an alarming rate. Anti-immigration parties have been gaining a lot of momentum recently. One of the right wing parties, the Alternative for Germany (AfD Party), won 25 seats out of 160 in the Berlin State elections after gaining a significantly smaller vote share of 4.7% in the 2013 Federal elections. Conversely, The Left Party in Germany has also enjoyed voter share growth, winning 15.6% in the State elections. The problem with polarisation is that, the more it intensifies, the lower the likelihood that political authorities can reach a consensus. In order to speed up the process of immigration, host countries must have coherent plans that avoid the backlogging of applications.

The reasons for this polarisation are multifaceted. The primary force driving anti-refugee sentiments is the belief that, if the refugees are to be afforded the same welfare benefits as German citizens, there will necessarily be fewer resources allocated to locals. However, according to migration expert Oliver Schmidtke, refugees may end up being a major help to the German economy: a flow of young working-age people helps alleviate some of the problems posed by a greying German population. Schmidtke believes that the relatively stable and profitable performance of the German economy since the 2008 financial crisis renders it uniquely suited to absorb such a refugee flow. According to OECD reports, Germany may especially benefit as a result of labour flexibility. People coming in from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and some eastern European countries have varying levels of education, skills and work experience, and thus integrating labour into the markets may help fortify and spur their long term economic output.

Secondly, Islamophobic attitudes have become increasingly prominent among some Germans. While several locals believe that political oppression should be condemned, many are also very wary of the number of Muslims entering the country. They fear radicalisation within their own borders.

Thirdly, many Germans are worried about a loss of German identity. These Germans claim that allowing refugees into the country increases diversity, an undesirable state of affairs that will ultimately erode German patriotism. Nevertheless, the culture of a warm welcome, or ‘Wilkommenskultur’ undoubtedly persists in Germany. The image of locals welcoming refugees with food, blankets and toys remains a common one, indicating the enduring appeal of left- wing and centre-left parties.

Another layer of analysis of the refugee crisis in Germany is the fact that up until these state elections, there has been no opposition to the refugee policy at the parliamentary level. All parties in the Bundestag effectively consented to mass immigration into Germany. Therefore, there are groups questioning whether the democratic regime genuinely represents the interests of the people, given the relatively equal divide for and against refugees. Furthermore, Germany’s recent growth figures have painted a less rosy picture of the country’s economic future. Some economists argue that due to low industrial demand from foreign markets, Germany finds it difficult to fund more infrastructure to support the refugee influx. Yet others argue that the dip in economic growth is simply a function of short term fluctuations, and that in the long term Germany’s output may increase significantly due to the increase in manpower.

Merkel’s refugee policy was ambitious yet flawed. Germany is currently struggling to accommodate over a million refugees due to the lack of infrastructure, as well as administrative clogs. However, it must be acknowledged that Germany is taking on huge responsibilities to make up for the more ambivalent attitude displayed by other EU members. The double-edged sword nature of this crisis is such that, in several states, including Germany, xenophobia and populism have increased along with refugee flows.

The key to the migrant crisis is widespread participation. Not only must EU countries help host refugees, but so should others who have the resources to support large numbers. In a humanitarian crisis involving such a rampant degrees of political persecution and constant danger to people’s lives, aiding asylum seekers fleeing from their countries’ regimes is a moral imperative. Regulation and registering processes must be conducted in a way that assists individuals ineligible for asylum in obtaining the required documentation, instead of simply allowing them entry either way or just sending them back to where they came from. This policy would need a larger ground staff and a boost in refugee aid to account for the extra time it takes to properly conduct documentation registering. However, this must be combined with a robust screening process to help reduce the effects of scaremongering and address legitimate security concerns. Given the imminence of German Federal elections in 2017 and the ascendancy of right-wing groups, Germany’s refugee policy could yet face significant revisions – if not a complete overhaul.