Global Giving and the Contradictions of Elite Philanthropy

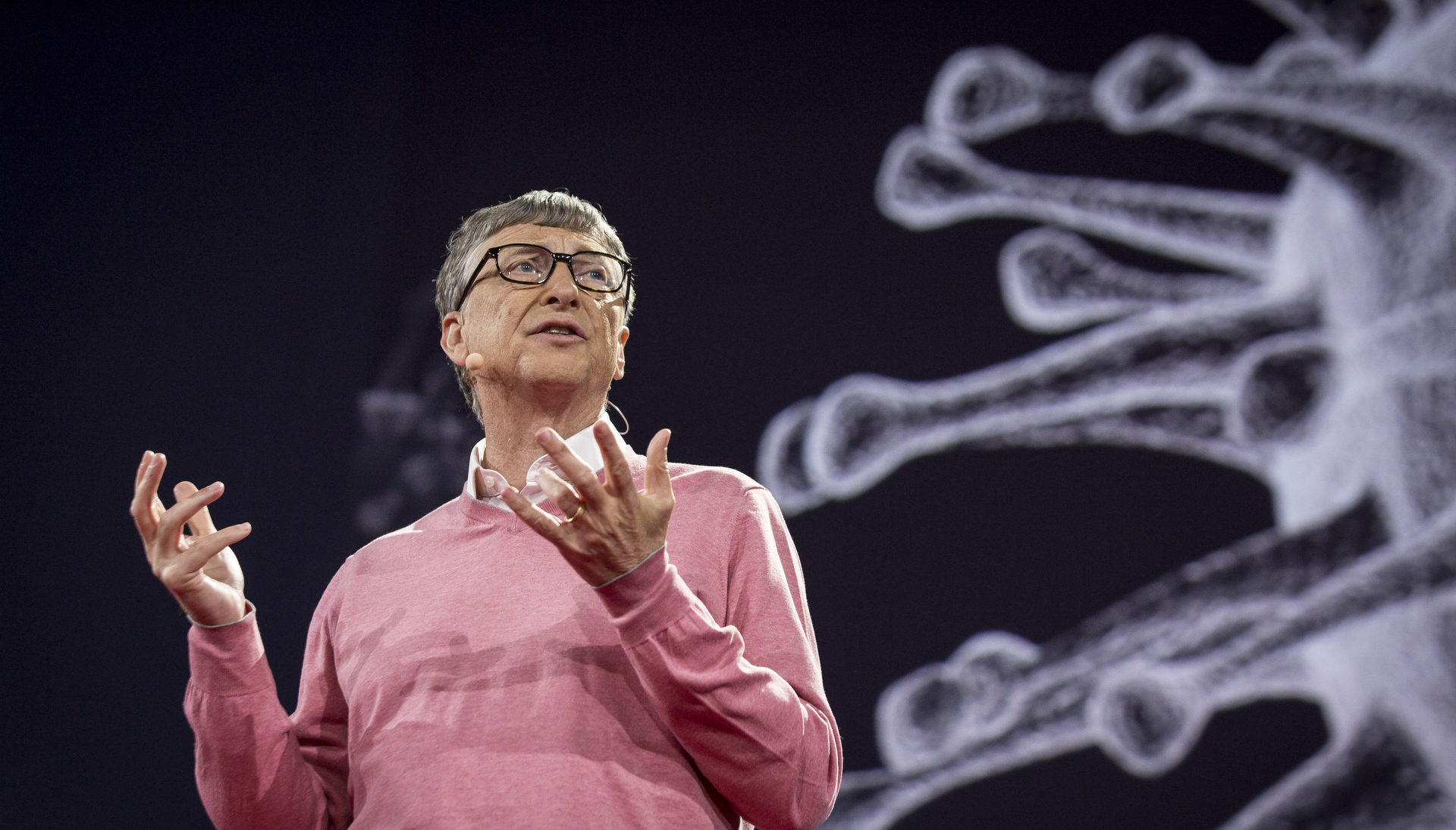

Bill Gates speaks at TED2015 - Truth and Dare, TED University, March 16-20, 2015, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Bill Gates speaks at TED2015 - Truth and Dare, TED University, March 16-20, 2015, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos made headlines when he and his wife, Mackenzie Bezos, donated $33 million to finance the education of 1,000 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients. Bezos’ contribution certainly appears praiseworthy, especially since DACA has been transformed into a political bargaining chip among Democrats and Republicans alike. Indeed, the Bezos have been lauded for “[setting] themselves apart from many other philanthropists” by “[wading] into activism” – presumably the kind of activism that challenges the views of President Donald Trump.

But Mr. Bezos’ supposed act of generosity begins to dwindle when we consider the fact that, as of January 20, 2018, he possesses a net worth of over $108 billion, making him the richest man on earth. The $33 million Bezos donated to DREAMers represents a meager 0.03% of the billionaire’s twelve-digit net worth.

This kind of philanthropy is noteworthy because as wealth inequality increases, those benefitting from the disparity often feel pressure to give back large parts of the wealth they have accumulated. In most cases, these billionaires are hailed for their generosity. But there would seem to be a contradiction inherent in a system of economic inequality and gilded giving. What kind of purposes does this philanthropy serve?

A Chocolate Philanthropic Laxative

A general trend can be observed when thinking about elite philanthropy: as wealth concentrates itself in fewer hands, there appears a rise in instances of philanthropic gestures by the world’s wealthiest people. As Bishop and Green have noted, “golden ages of wealth creation give rise to golden ages of giving.” [1] Philanthropic generosity would then seem to act as a “release valve” to correct the “worst excesses” of a system of massive wealth inequality. [2] The interesting thing about this inequality is that it exacerbates the very problems that wealthy philanthropists are so eager to solve. Higher economic inequality is correlated with a lower life expectancy, lower rates of education, and higher rates of poverty.

There is a cognitive dissonance in the notion that the purveyors of inequality can also be the messiahs of wealth redistribution. This has not gone unnoticed. To illustrate this point, philosopher Slavoj Žižek uses the example of an advertisement for a chocolate laxative: the thing that causes constipation (chocolate) is marketed as its cure (the laxative). [3] In the same vein, billionaire philanthropy is meant to project an image of “a system that exploits but still cares, wreaks social havoc but really worries, institutes a Wild-West entrepreneurialism but also a welfare state.” [4]

Elite philanthropy embodies the contradictory nature of the chocolate laxative, especially given the fact that the wealthy are seeking to remedy inequity with the very wealth they have accumulated as a result of unequal economic structures. Socioeconomic trends reflect the contradiction. A January 2018 report from Oxfam found that 82% of all wealth created in 2017 went to the richest 1% of the globe. A similar study by Oxfam in 2017 found that the eight richest men on earth have the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of the globe. The growth in inequality is staggering, especially when one considers that the philanthropy practiced by the ultra-wealthy is supposed to resolve issues of inequality. Nevertheless, the rich have managed to get richer.

Getting Creative

Perhaps the most high-profile philanthropist of the present day is Bill Gates. Now the second-richest man on earth, with a net worth of $92.3 billion, Gates rose to philanthropic fame with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a private foundation established by Gates and his wife, Melinda, in 2000. Gates has sunk approximately $50 billion of his own wealth into the foundation as of 2017.

The Gates Foundation operates on the primary guideline that “all lives have equal value.” It is this founding principle that motivates the Gateses to tackle global issues of “extreme poverty and poor health in developing countries, and the failures of America’s education system.” Gates himself believes that most of the world’s ills have attainable solutions, but that there is no economic incentive to meet the needs of the world’s poorest and most disadvantaged people. Because poor people do not have the ability to pay for goods and services they need to survive and live fulfilling lives, there is no incentive for any rational profit-seeker to offer those goods and services.

This assessment is not a structural problem for Gates. The fact that the current system of resource allocation is massively under-serving huge swaths of the global population does not mean it is beyond hope: Global issues of poverty, healthcare, and education can be appropriately solved by working within global financial markets in order to fix their inefficiencies.

To this end, Gates employs what he calls “creative capitalism.” Creative capitalism encompasses a process of harnessing market forces such that wealthy individuals, corporations, and NGOs can meet the needs of the world’s poorest while still turning the profits or gaining the recognition necessary to incentivize these groups to do so. [5] As Gates argues, “the genius of capitalism lies in its ability to make self-interest serve the wider interest.”

From Gates’ perspective, the only way to innovate in charitable spheres and progress on issues of inequality is to give the world’s wealthiest an economic incentive to give their money away. It is not surprising, then, that The Gates Foundation has been at the forefront of efforts to facilitate private-public partnerships between corporations and governments in the Global South. These efforts include encouraging corporate farming and working with big agribusinesses to push corporate biotechnology on several countries in Africa.

Movers and Shapers

Despite the opportunities for “creativity” latent within elite philanthropy, Gates explains that his main motivator to be charitable comes from personal satisfaction: “the most fulfilling thing [he has] ever done.” Regardless of the personal motivations of these elites, the philanthropic process presents the added benefit of being able to significantly shape and influence public policies to their own ends.

Early American philanthropists knew this much. A notable portion of the early philanthropic work by wealthy industrialists like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie was designed to temper the anti-capitalist sentiment that was pervasive in some circles during the early twentieth century. For example, Rockefeller founded The General Education Board in 1902, which sought to reshape Black education such that it would be “economically useful and politically harmless.” [6] Similarly, money from Rockefeller, Carnegie and many others went toward the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. In the 1920s, the NAACP served the ideological purpose of neutralizing popular support for the American Communist Party among Black people. [7]

The elites of today have also seen the policy-shaping benefits of doling out billions of dollars in accumulated wealth. A notable arena for this kind of policy-shaping is American public schools. There are several foundations and wealthy individuals that have come out in favor of education privatization. For example, The Walton Family Foundation, established by Walmart founder Sam Walton, is a supporter of charter schools as a replacement for public schools, and offers grants for groups that wish to found their own schools.

Gates has also thrown his hat in the education reform ring. Gates has extolled and invested in charter school development in the past, but is open to the idea of reforming traditional public schools as well. Gates initially believed that classroom size was doing public education the most damage, and spent $2 billion to experiment with 8% of America’s public schools before realizing that classroom size had no noticeable effect on student performance.

Undeterred, Gates shifted focus to teacher effectiveness. The Gates Foundation was central in the development of the Common Core Standards, a set of educational standards laid out by the federal government for each state to adopt in order to standardize the education system. Barack Obama also instituted the Race to the Top (RTTT) program that sought to incentivize public schools to implement reforms in exchange for federal funding, which brought many states to adopt Common Core as part of RTTT’s demand for the implementation of common standards.

Such initiatives were a boon for Gates, as they allowed for a more accurate way of determining teacher effectiveness, since there would be national performance standards against which students would be compared, and to which teachers would be held accountable. This process introduced the application of free market forces to the educative sphere. As Nicole Aschoff explains, the market philosophy indicates that “the product of education (test scores) will be improved when educational production processes (teachers) transform the inputs (students) with more skill and efficiency.” [8]

Aschoff decries the commodification of education by billionaires like Gates because it means that education is “no longer a right, or even potentially a right. It also means that the commodity’s value is now judged primarily on whether it will turn a profit, and the people’s access to the commodity hinges upon their ability to pay for it.” [9]

Missing the Point

Absent from the conversation about education reform is the fact that it is not the quality of teachers negatively impacting student performance in America’s poorest neighborhoods; it is poverty. Studies show that poverty is linked with poor performance in school, and slower brain development, among other things. But this conversation is rarely discussed by billionaires like Gates and Bezos.

Few are discussing the fact that Bezos’ $33 million contribution to 1,000 DACA recipients paints a damning picture of an expensive education system that bars access to millions who cannot afford to go to college. The fact that Gates’ wealth has managed to grow even as he gives billions of it away is seldom questioned. Fewer still are willing to challenge the market logic that facilitates systems of inequality in the first place.

The fact is that a system of increasing wealth inequality plays a large role in explaining why parts of the world remain impoverished, malnourished and in disarray. Those living in poverty do not require more of a market that does not serve their needs, nor do they require the benevolent gestures of a wealthy few. They require governments, social services, and community links that will look out for their best interest.

We must come to grips with the fact that when the kind of wealth that is controlled by the likes of the world’s richest people is kept out of the public sphere, education will naturally suffer. Governments will naturally not be able to provide healthcare, food, and housing to those suffering the most under a system of economic inequality. We should not, then, praise billionaires who find themselves touched by the plight of the people who have nothing and decide to give back. These actions should be expected, and demanded.

If the billions of dollars controlled by the world’s wealthiest people were democratically controlled through a system of taxation and redistribution, there is no telling the kinds of social, political and economic justice that could be achieved. We get nowhere as a society by praising the rich simply because they are rich, nor do we advance by applauding them when they decide to give back. We advance by getting into the driver’s seat and using our power to shape society ourselves.

Edited by Luca Loggia

Feature Image: Bill Gates speaks at TED2015 – Truth and Dare, TED University, March 16-20, 2015, Vancouver Convention Center, Vancouver, Canada. Photo: Bret Hartman/TED. Flickr Creative Commons.

_______________________________________________

[1] Matthew Bishop and Michael Green, Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich Can Save the World (New York : Bloomsbury Press, 2008) 21.

[2] Nicole Aschoff, The New Prophets of Capital (New York, NY: Verso, 2015), 113.

[3] Ilan Kapoor, Celebrity Humanitarianism (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), 62.

[4] Kapoor, Humanitarianism, 62.

[5] Aschoff, Capital, 116.

[6] Joan Roelofs, “Foundations and Collaboration,” Critical Sociology 33 (2007): 481.

[7] Roelofs, “Foundations and Collaboration,” 482.

[8] Aschoff, Capital, 131.

[9] Aschoff, Capital, 127.