Hariri’s Mosaic

Divide in a unity government

https://bit.ly/2IhGEGd

https://bit.ly/2IhGEGd

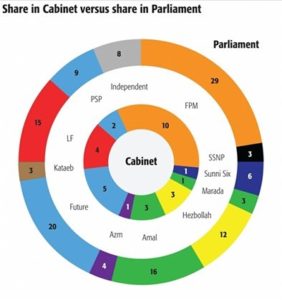

Nothing exemplifies Lebanese politics more than the fact that it took 254 days for a prime minister to form a cabinet. The endless complexity of the confessional system makes consensus seem impossible, and yet that is exactly what Sunni Prime Minister Hariri is attempting to do. His government is a united coalition formed by most of the parties in the Lebanese parliament. It includes members from the two divided factions, the March 8 and March 14 movements, and features a record number of women in a country largely opposed to women holding significant seats in government. Against all odds, Hariri is making a progressive achievement of multi-partisan governance. However, Hariri’s greatest challenge will be to keep this seemingly utopian cabinet united in the face of diverse internal interests and external threats. Through every issue and policy decision, he will have to choose between his Sunni Muslim base in the Future Movement (FM) and the different members of his coalition. Combine this with outside pressure growing on the issues of Israel, Syria, and Hezbollah, and his tenure might be short lived.

The new government was finally formed on the 31st of January 2019. Notable members include the health minister Jamil Jaback, an independent cardiologist with strong ties to Hezbollah. De jure under the command of Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah, Jaback’s appointment sparks fear of ministerial funds going to terrorist activities. The environment minister Fadi Jreissati, a member of President Aoun’s Freedom and Patriotic Movement (FPM) is also of interest. Jreissati is both a CEO of a major real estate company and the head of the Lebanese National Energy Association (LNEA). He has yet to show any intent of resignation from either institution, and he is in a position to use this conflict of interest to promote his own corporate projects to the possible detriment of the environment.

The concerns here lie with the increasing conflicts of interest and with the near veto power of the president’s party, the FPM, in cabinet. In a country notorious for sectarian clientelism, Hezbollah will almost certainly exploit its gains. Furthermore, President Aoun’s pro Syrian FPM has control over The Ministries of Defense, Justice, Economy and Trade, Energy and Water, the Displaced, Foreign Affairs, and the Environment. Government funds will be taken away from the wellbeing of all citizens and instead be directed toward the health of these parties’ bases. In the case of Hezbollah, it may even directly fund militant activity. This is further exacerbated by the pro-Syrian March 8th bloc’s control of parliament, within which Hezbollah is a significant member. With these gains, we may see a further pivot of Lebanon toward Syria, and by extension Iran. Prime minister Hariri, himself a member of the anti-Syrian March 14th block, will have little power to oppose such a chokehold from above through the president and below through his cabinet.

Abroad, Hariri faces two issues of contention. The first lies in Syria. With Hezbollah’s continued involvement in Syria, and with more than a million refugees within Lebanese borders causing social and economic unrest, the government might face pressure to comply with the Syrian government and accelerate the return of mostly reluctant refugees to a continually violent country.

On top of all that, there’s Israel to contend with. The continued threat of Hezbollah in Syria, the discovery of their tunnels in the south of Lebanon, their increasing influence in government, and the rising disputes over offshore oil reserves may lead to the reignition of conflict between the IDF and Hezbollah in the near future. With Israel carrying out overt raids on Iranian positions in Syria, and with a battle-hardened and armed Hezbollah ready for their next war with Israel, both sides seem emboldened to become more active in the region.

Yet, with all of these concerns over geopolitics, and despite the immense delay in its appointment, the cabinet has taken off to a flying start domestically. Within days the government achieved a consensus on their policy statement towards parliament, allowing them to win a strong mandate with the confidence of 111 of 117 MP’s on the 15th of Febuary. Through a process that usually takes upwards of thirty days, this rapid decision-making signals a relatively strong coalition underneath Hariri. With the vote secured the government can proceed towards implementing vast economic reforms and begin to plan for the next great hurdle: The budget.

Hariri vows to unlock the 11B$ in grants and soft loans pledged in the “Conférence économique pour le development, par les réformes et avec les entreprises” (CEDRE), which he plans to do through a 5% reduction in the government’s deficit over the next 5 years. This austerity involves a reduction of the 2$ billion in energy subsidies in a country which can only cover half its energy at peak demand. Such austerity measures will not be popular, possibly leading to civil unrest similar to events in Egypt and Sudan when they introduced austerity measures on essential needs.

Saad Hariri leads a mosaic of a government, laid on a background of debt and foreign conflict. He has sought to create a unity government where division of powers between opposing religious sects and their respective parties are enshrined in the constitution. This dream stands against all odds. His cabinet is on the path to transforming a state starved of basic domestic functions. Yet, despite surprising most in terms of its short-term efficiency, his cabinet faces multiple challenges that will threaten its cohesiveness, and this fragile work of art might quickly fall apart.

Edited by Gracie Webb