Harvey, Irma, and the Implications of High-Risk Gambling

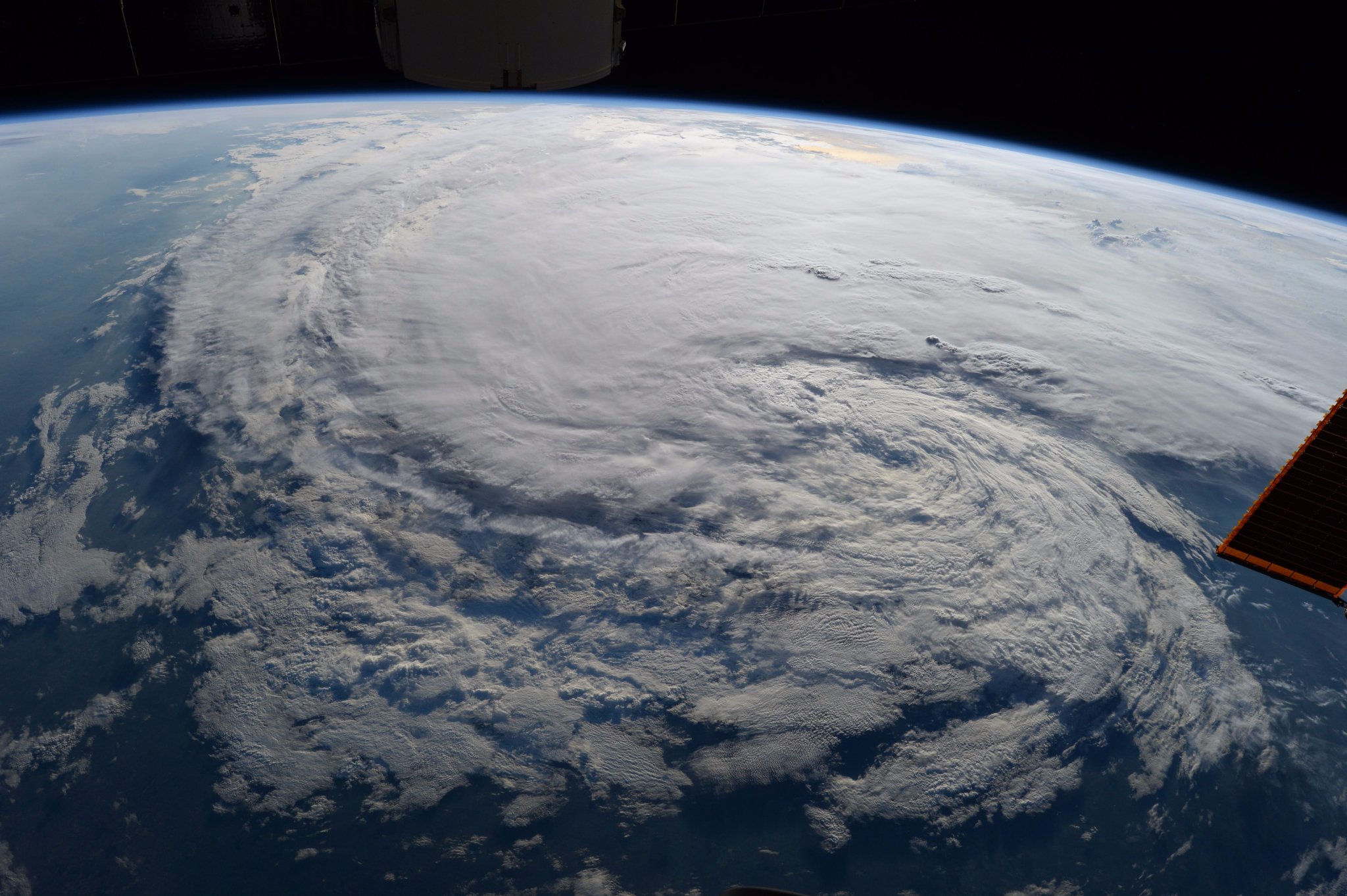

Hurricane Harvey captured by NASA, August 2017.

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/36724564692/in/photostream/

Hurricane Harvey captured by NASA, August 2017.

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/36724564692/in/photostream/

It’s September 10th in Florida. Evacuations have taken place, reporters are feverishly on their feet, Irma is about to hit. Floridians brace themselves as best as they can for disaster. The hurricane has already destroyed multiple islands in the Atlantic Ocean and is not going to spare their state. Others across the world are likewise fearful, but not because their livelihoods are at stake. They’ve made a bet on the catastrophe, in the form of catastrophe bonds, and are afraid of losing sizeable amounts of money.

Catastrophe bonds, often referred to as “cat bonds,” are a financial product sold by insurance companies. The bonds are designed to grow insurance companies’ emergency funds in the case of a wide-scale disaster to minimize losses incurred if it strikes. Cat bonds expire after a set period of time, usually three to five years. Investors, typically large corporate groups, get their initial investment back after the bond expires, but only if no cataclysm occurs.

What makes cat bonds an increasingly popular type of investment are the potentially immense yields at stake. Yearly returns on investment that investors receive are around 8.5%, compared to around 5% with more traditional government or corporate bonds. Another attractive factor is that cat bonds are part of the “uncorrelated asset class”, which means that they aren’t linked in any way to other financial markets, such as the Dow Jones. Markets could crash, but cat bonds’ value wouldn’t budge.

The inaccuracy of predicting natural disasters, however, makes cat bonds a particularly risk-heavy investment, which experts in climatology and financial markets have attempted to denounce for over a decade. A wide-scale, unpredicted natural disaster could make investors lose colossal sums of money all at once, thus creating a financial vacuum in the global economy. This, undoubtedly, would cause a significant market crash with proportions akin to those of the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis.

The surge in demand for cat bonds is part of a wider high-risk gambling trend which, ironically, emerged after the 2007 crisis and subsequent global recession. The most lucrative cat bond markets are geared towards wealthy industrialized countries, particularly the United States. In the U.S., generally few households are insured in case of a natural catastrophe, even in hurricane-prone coastal Florida, where only 45% of them are. The proportion of people afflicted by climate-related catastrophes in the United States has moreover steadily increased since the beginning of the century, with more than two million people having settled in high-risk areas in Florida since 2005, for instance.

Ethically speaking, the value of the cat bond market thus ranks poorly, since purchasing a cat bond is, in essence, betting on the probability that millions of persons’ livelihoods will or won’t be compromised. This moral divide is only set to become deeper as time goes by and the frequency and gravity of natural disasters inevitably rise due to climate change. Scientists around the world have repeatedly demonstrated that recent hurricanes’ unusually strong intensities, including those of Harvey and Irma, are directly linked to climate change. In the U.S., the political imbroglio surrounding the issue of climate change only serves to add fuel to the fire, since the Trump administration’s indifference to the environment downplays risk, further encouraging disconnected behavior on the part of financial actors in the cat bond market. The market’s size is currently at an all-time high of $30 billion and is projected to keep growing exponentially as a consequence.

The cat bond market therefore urgently needs regulation of its structure to avoid a financial debacle. There are, for example, no objective or uniform criteria to determine whether insurance companies may tap into investor money to alleviate costs associated with a catastrophe. In the case of hurricane Harvey, investors were allowed to keep the entirety of their initial cat bond investments because flooding isn’t covered by that type of bond. This entails that governmental agencies like the E.P.A., as well as insurance companies, presently have to provide substantial funding to usher Texas back into normality, while continuing to pay investors the 8.5% return on their initial investment.

Catastrophe bonds’ opportunistic nature may appear cynical to many, and that’s because it is. Betting on misery is not a foreign concept to financial markets. The questionable existence of subprime mortgages or, more recently, that of terrorism bonds, come to mind. Even more appalling than investor insensitivity is the ease with which they repeatedly slide back into destructive, age-old habits – and how well they get away with it, every time.