House of (Credit) Cards: Disjuncture between Public Opinion and Policy

On March 23rd, McGill University Principal Suzanne Fortier issued a statement that shocked many within the McGill community. Through an email to university faculty and students, Principal Fortier relayed the Board of Governors’ decision to not divest from corporations tied to fossil fuels.

On March 23rd, McGill University Principal Suzanne Fortier issued a statement that shocked many within the McGill community. Through an email to university faculty and students, Principal Fortier relayed the Board of Governors’ decision to not divest from corporations tied to fossil fuels.

The statement has left many students and faculty puzzled. The fundamental puzzle to these individuals, particularly those part of Divest McGill (the student group spearheading the move to divestment), revolves around a basic question not unfamiliar to political scientists studying representative democracy: How is it that a legislative or administrative body can choose to ignore massive popular activism for a certain cause and still claim to be representative? This question, as it turns out, runs to the core of a central discussion among scholars of American politics today. It has scholars asking the question: How is it that many policies, despite massive popular support in favor of them, fail to become law or never even reach Capitol Hill?

The answer to this question lies in the American government’s special relationship with special interest groups. It can be said that the powerful influence of different interest groups in the United States fuels this disjuncture between public opinion and policy.

The problem at hand is more widespread than some acknowledge it to be. Proposals ranging from gun control to LGBTQ rights have numerously failed to become law in Washington despite visible popular support.1 2 3

Washington’s failure to recognize popular demand for environmental reform in particular has become an alarming routine in American politics. Almost every major piece of environmental legislation proposed in past U.S. Congresses have faced serious uphill battles from their onsets, despite major public support. According to a Pew poll conducted in 2014, 64% of U.S. adults favored setting stricter emissions limits on power plants to address climate change, with only 31% opposing.4 From the same survey we learn that in 2009, 85% of U.S. adults believed climate change was occurring and that in 2014, 60% of U.S. adults said that alternative energy sources “should be [a] more important priority for addressing America’s energy supply” over expanding the exploration and production of fossil fuels.

And yet, when we look at major environmental protection and climate change abatement policies in the United States, successes are few and far between. During the 111th session from 2009 to 2011, Obama and both the Democrat-controlled houses of Congress had their best chance at passing meaningful climate policies. In the end, no major bill in the ranks of the Clean Air Act (1965) or Clean Water Act (1965) regarding climate change was passed during the 110th, 111th, and 112th Congresses, despite campaign promises of a stronger focus on combating climate change.5

This was not for lack of trying on President Obama or the Congressional Democrats’ part. During the 111th Congress, several bills were introduced to address global climate change. Most notably there was the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009, often referred to as the Waxman-Markey bill, which proposed a cap and trade system as well as a multitude of other provisions, such as requiring retail electricity suppliers to meet 20% of their demand through renewable electricity among others. This Waxman-Markey bill passed the House with a vote of 219 to 212, but it was never brought to the floor of the Senate for a vote.6

Failure to pass a major climate change bill underscores the puzzling relationship between public opinion and public policy in the United States. Why did the bill fail when Democrats controlled both houses of Congress, the President had been voted in on his campaign including environmental protection, and the supermajority of American adults called for restricting carbon emissions from power plants?

As aforementioned, the United States’ political affinity to interest groups, their lobbying, and campaign finance laws create this puzzling divergence between what the masses want enacted and what the government actually enacts. Interest groups and campaign finance organizations’ overhanded influence in policy-making, thus, endanger American principles of democracy. The impact of special interest groups on Congress outweighs the government’s consideration for public opinion, as is empirically evident in the analysis of the Waxman-Markey bill.

As Kim et al. point out in their in-depth analysis of lobbying for and against the Waxman-Markey bill, this particular piece of environmental legislation was the ninth most lobbied bill among all American federal legislation — and rightfully so. Millions of dollars were at stake for either side, which heightened competition among lobbyists. The financial and influential arsenals of those with stakes in fossil fuels greatly prevailed over those claiming to represent the American people. One study found that, in general, for every $1 spent on lobbying by labor unions and public-interest groups in the U.S., larger corporations and their associations spent $34.7 It’s not hard to see how this financial disadvantage of 1:34 in favor of corporations over the public contributes to the squashing of bills supported by the general public.

In the case of the Waxman-Markey bill, that’s exactly what happened. In the end, lobbying efforts against the bill won over the proposition. Among the lobbyists was the American Coalition for Clean Coal Energy (ACCCE), which “spent almost $15 million in lobbying activities in the years 2009-2010, mostly to undermine climate legislation.”8 The final blow to the bill was delivered when opponents organized themselves under the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, protesting the Waxman-Markey cap system was a “terrible option” and strongly urging Congressmen to reject it (Kim et al.).9

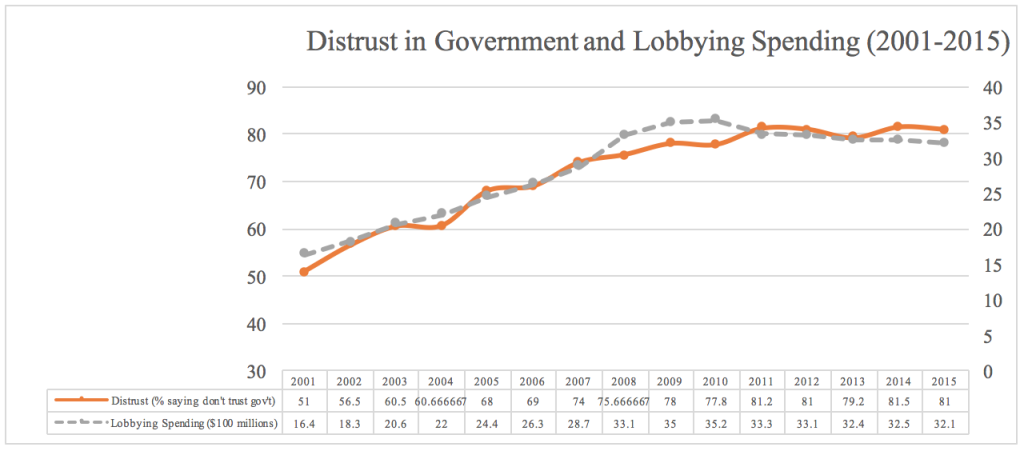

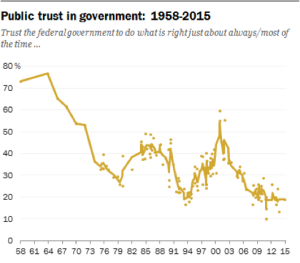

Examples of failed bills like the Waxman-Markey outline how lobbying is one of the strongest driving forces in American politics in the 21st century. It no longer seems that members of Congress can independently and unequivocally represent the wishes of their constituents. And this is reflected in public polls. In 2015, one poll finds, 74% of surveyed U.S. adults agreed with the statement: “most elected officials don’t care what people like me think.”10 It isn’t a far leap to say that this increased negative perspective of elected officials translates into overall distrust in the American federal government, as represented by the fact that only 19% of American adults say they trust the government in Washington at least “most of the time.”11

This distrust of Washington has serious implications for the quality of democracy in the United States. Voter turnout, an already at-risk political institution in the United States, is bound to take hits from distrust and apathy towards the government. As voter turnout decreases, accountability of elected officials to their constituents is even further diminished as legitimacy derives less from democratic votes and more from large campaign finance donations, as permitted by Citizens United. Public skepticism of the government and incongruity of Congress’ policies with public opinion will perpetuate in a cycle, and if left untreated, will eat away at American democratic legitimacy.

Overall, the unique power of interest groups in the United States to influence policy at the cost of the public’s wishes has serious implications for American democracy, namely the injuring of democratic values such as government “by the people” and, subsequently, “for the people”.

With regards to the current climate debate at McGill, this conclusion tells us much about the Divest McGill movement and the accountability of administrators at McGill to their students. The rift between administration and students at McGill is a product of decisions made by individuals who have chosen to listen to the few instead of the many. One consequence of short-term decisions that contradict massive popular support is unsustainability: how much longer will concerns held by thousands of university students be ignored by their administration? Using the same line of logic: how long will the American people’s concerns about climate change be pushed to the side by policymakers in favor of corporate interests and campaign donations? The answer to both of these questions: hopefully not long.

To get this ball rolling on preventing their preferences from being constantly silenced, the McGill community and the American public must demand their respective governing bodies to allow more direct consultation on policies that affect them. As we have seen, however, popular support does not necessarily always translate into policy. Thus, the ultimate challenge is to break the cycle of being silenced.

Works Cited

1 Polling Report. “Guns.” Polling Report. Polling Report, Inc., n.d. Web. 06 Apr. 2016.

2 http://www.responsiblelending.org/other-consumer-loans/consumer-financial-protection-bureau/research-analysis/CFPB-poll-2-writeup-v3.pdf

3 http://www.pewforum.org/2015/07/29/graphics-slideshow-changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/

4 http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/07/01/chapter-2-climate-change-and-energy-issues/

5 Kim, Sung Eun, Johannes Urpelainen, and Joonseok Yang. “Electric Utilities and American Climate Policy: Lobbying by Expected Winners and Losers.” Journal of Public Policy (2015): 1-25. Cambridge Journals. Web. 06 Apr. 2016.

6 http://clerk.house.gov/evs/2009/roll477.xml#NV

7 Drutman, Lee. “How Corporate Lobbyists Conquered American Democracy.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 20 Apr. 2015. Web. 06 Apr. 2016.

8 Kim, Sung Eun, Johannes Urpelainen, and Joonseok Yang. “Electric Utilities and American Climate Policy: Lobbying by Expected Winners and Losers.” Journal of Public Policy (2015): 1-25. Cambridge Journals. Web. 06 Apr. 2016.

9 Ibid.

10 http://www.people-press.org/2015/11/23/6-perceptions-of-elected-officials-and-the-role-of-money-in-politics/

11 http://www.people-press.org/2015/11/23/1-trust-in-government-1958-2015/

12 The Center for Responsive Politics. “Lobbying.” Open Secrets. The Center for Responsive Politics, 22 Jan. 2016. Web. 06 Apr. 2016.

13 Pew Research Center. “Public Trust in Government: 1958-2015.” Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Pew Research Center, 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 06 Apr. 2016.

Image at the courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons. Modified to fit.