How Data Helped Big Tech Monopolize Modernity

On October 6, 2020, the United States House Judiciary Committee released a report condemning the anticompetitive business practices of Amazon, Apple, Google, and Facebook. The “Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets” is the culmination of a 16-month long investigation into Big Tech companies, and describes how they established monopolies and subsequently abused their market power.

The report also recommends a range of action that would substantially change the technological field, including the introduction of explicit laws to prevent Big Tech from preying on smaller companies and increased funding for antitrust enforcement agencies. Democrats also took it one step further by proposing fundamental restructuring of the four companies to reduce their hold over a variety of technological markets. However, these proposals fail to address the underlying problem: these companies monopolized the digital age by hoarding massive amounts of user data.

Facebook and Amazon collect as much information about their users as possible. They ask for some of it — names, emails, personal photos, home addresses — but they also have the ability to learn about users by gaining access to the devices used to browse their platforms. By having users agree to lengthy Terms of Service riddled with subsections linking data collection to improved user experience, Amazon and Facebook know what Wi-Fi networks their users connect to, where they are, what version of iOS they’re using, and can access all the data collected by other apps on their devices. Furthermore, although Facebook has already been scrutinized for questionable data practices, it continues to create “shadow profiles” of people who are not even on Facebook, based on the information Facebook users have about them on their devices.

Facebook does not collect information about its 2.6 billion users and all their friends because Mark Zuckerberg is nosy; rather, they collect information so they can predict actions. By collecting as much information as possible, Facebook can use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to predict user behaviour. The algorithms are told what users like, then instructed to predict what they may like in the future; as users repeatedly engage with the algorithm, it becomes ‘smarter’ and can make predictions with a higher degree of accuracy. The company then uses these predictions to feed users personalized content that it knows will reflect their preferences with unmatched accuracy. Smaller companies do not have access to this staggering amount of data, and therefore cannot predict user interests as well as Facebook can. Rather than a social media platform, Facebook becomes akin to a friend that knows you better than you know yourself, giving it the power to attract users away from the competition. When predicting behaviour does not work perfectly and other companies start becoming competitive, Facebook simply buys the competitor or copies their interface.

Zuckerberg didn’t invent this data-based business model — Jeff Bezos did. In fact, for all intents and purposes, Amazon is a data company; Bezos has considered user data a commodity since 1997, earlier than just about anyone else. By hoarding it since the inception of his company, Bezos built a consumerist empire that meticulously tailors to consumers’ wants and interests, keeping with his motto of “putting the customer first.” Amazon uses data to predict user behaviour, but also to mitigate the usual risk of selling a product. Normally, business owners can never be entirely sure of the products their future customers will want and how much they are willing to pay — but Amazon does. Because the company has enough information about its users to predict this, it can sell goods with minimal risk and push other companies out of the market for nearly every product imaginable.

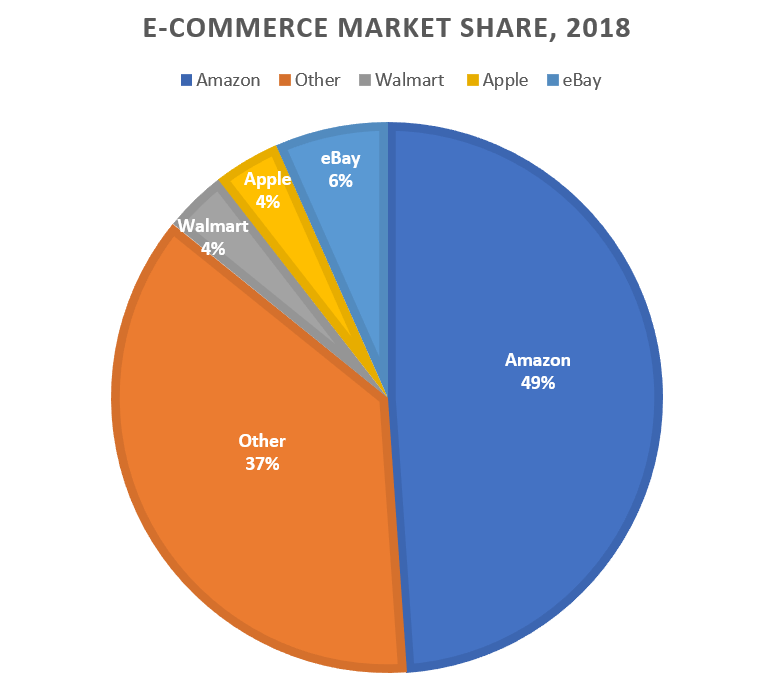

Furthermore, Amazon has the ability to sell at a loss, allowing it to undercut smaller businesses that cannot compete with going bankrupt. Suppliers are aware of this reality, making it nearly impossible for them to refuse an offer to sell their products through Amazon Marketplace — despite knowing that they will not have access to the data stockpiled by the giant. In some cases, if a product by a third-party supplier sells exceedingly well on their platform, Amazon will create a copy of the product, sell it at a loss, and force the original supplier to fold. As a result of this malicious business practice, Amazon holds 49 per cent of the American e-commerce market — seven times the market share controlled by its closest competitor, eBay.

Amazon and Facebook’s power is only set to grow. They have each established a monopoly within their respective markets simply by collecting more data than their competitors, a habit which shows no sign of stopping, blurring the lines of privacy at an alarming rate. Although Zuckerberg and Bezos appear to only be keen on remaining competitive in a notoriously cut-throat technology industry, there is no telling how much further they will go in predicting the behaviour of the masses. Without proper government regulation, there is very little to prevent these companies from watching, predicting, or inspiring our every move. The consequences of this power are dire: the House report directly attributes the erosion of user privacy and the propagation of misinformation on Facebook’s platform to the absence of any real competition, while Amazon’s predatory practices have reduced the e-commerce “market” to the company’s own playground.

While the concentration of these platforms may be convenient for consumers, they are fatal for the once innovative tech industry, and American legislators understand that. By failing to impose stricter data regulation on Big Tech giants like Facebook and Amazon, government officials are displaying a fundamental misunderstanding of these platforms. Personal data has never been worth more, nor so vulnerable. The recommendations outlined by the House report are not enough. The time for a conversation about data rights and limitations is over: we need action.

Featured image by BP Miller, licensed under Unsplash

Edited by Justine Coutu