How Does Claiming Asylum in Canada Even Work?

Deciding to seek asylum is complicated, both practically and emotionally. Designing a system to receive asylum seekers that is both compassionate and fair is too. From Europe, to Brazil, to the southern U.S. border and more recently Canada, debates on how to best ensure justice have captured the general public’s — and politicians’ — attention as one side argues for prioritizing order and security and the other for maintaining compassion and openness. These debates vary in their intensity, yet, as confusion is exploited for personal gain and governments fail to admit their shortcomings, they have become more divisive.

Canada, thanks to its geography, is physically isolated from the rest of the world, yet Canadians generally pride themselves on their openness to others, especially those in need. However, at present, Quebec’s new government has pledged to reduce immigration, Ontario under Doug Ford questions whether provinces should financially support refugees, and for the first time in modern Canada, a party questioning multiculturalism has formed. Adding to this, and likely to be an issue in the 2019 Federal Election, has been a notable increase in asylum seekers at the Canadian border.

Driving these responses are questions concerning the fairness of the process, whether the system is managing increased claims, and if Canadian (and Quebecois) values – including acceptance – are at risk. These debates hinge on what happens to asylum seekers during the process, yet little explanation exists of these details, especially at the political level. So, let’s take a look at it, from when the decision is made to seek asylum in Canada, to arrival here, to what happens after the border is crossed.

The Decision Stage

1. An individual leaves their country of origin after concluding that it is unsafe for them or their family. This can be due to persecution, violence, discrimination, natural disasters, or economic hardship.

2. Under the Safe Third Country agreement, they legally must claim asylum in the first “safe” country they come across. Canadian land arrivals always go through the United States, meaning almost all asylum seekers arriving at official land crossings will be denied entry – regardless of the strength of their claim.

3. Many asylum seekers, still feeling unsafe, continue on to Canada, at times joined by those living in the States who now fear deportation. A variety of American policies, including removing domestic abuse and gang violence as grounds for asylum, the revocation of humanitarian work permits for those from dangerous countries, aggressive immigration enforcement – including the separation of families – and questioning the legal status of currently protected individuals intensifies these concerns.

Arriving in Canada

1. Unable to legally claim asylum at official border crossings, crossings occur at unofficial points, most of which have been in Quebec. Once across the border, the government is required by Canadian and international law to process these claims.

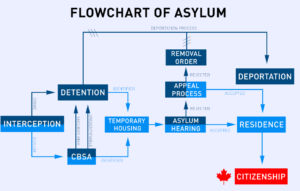

2. Asylum seekers get intercepted by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). If they are found to have drugs or illegal substances they are arrested. The RCMP attempts to verify their identity and determine if they pose a security risk, for instance, if they have a criminal record or are on watchlists pertaining to terrorism or organized crime.

3. Once the asylum seeker states their intentions, the RCMP hands them to the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) for their claim to be processed. In the case of Quebec crossings, they stay at a specifically built camp near the border. During this time the asylum seeker is not considered detained or under arrest because they are free to go back across the border.

4. If the asylum seeker’s identity cannot be quickly confirmed or they are deemed to be a security threat, they are detained by the CBSA and transported to a detention centre. If there are no issues, they are given a date for an asylum hearing and allowed to stay in Canada for the duration of the process.

Post-Arrival (If Detained)

1. In the case of Quebec crossings, the detention centre is a repurposed prison in Laval. Once here, the asylum seeker must have a hearing within 48 hours to confirm their detention. Additional hearings are held a week after their arrival, and then every 30 days. If the detention is justified, they remain in the detention centre until their identity is established, or in the case of security threats until their legally required deportation hearing.

2. While in the detention centre the asylum seeker’s movement and schedules are restricted, if they have to leave the centre for legal or medical appointments they are escorted by CBSA agents and handcuffed for the duration of the visit. If they require hospital admission they are also shackled at the feet.

3. Once the asylum seeker’s identity is verified – which can vary significantly in length – they are released from detention to rejoin the asylum process for those not detained.

Post Arrival (After Detainment or if Not Detained)

1. Asylum seekers are transported to temporary housing with relatives, community groups, or in publically run shelters, while they await an asylum hearing. They are asked whether they intend to stay in Quebec or Ontario, then sent to one of the two. In the case of Quebec, the destination is generally Montreal. In Ontario, it is spread across multiple cities.

2. Once here, asylum seekers receive support from various charities, public groups, and non-governmental organizations. This includes getting their children into schools, occupational training, and legal assistance. During this time, they also receive social assistance support from the provincial and federal governments.

3. An asylum hearing is held where the asylum seeker is asked questions by a board member of the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB). Someone from the CBSA may be present to oppose the claim. The board member, who is not a judge but trained to assess cases, decides whether to reject or accept the claim at the end of the hearing.

4. If the claim is rejected[1], the asylum seeker has 15 days to appeal the case, and the asylum seeker receives a removal order– meaning they must leave the country within a specified timeframe or face arrest, detention, and deportation. An appeal can sometimes be granted on humanitarian or compassionate grounds.

5. If the claim is accepted, the asylum seeker can claim permanent residency.

The system may be long, but it is under pressure from a variety of fronts. Outside of its control are an unpredictable neighbour and the conditions driving people from their home countries in the first place, such as poverty, environmental crisis, and violent conflict. It seems that the increase of asylum seekers – and of public attention – has caught the government by surprise as immigration policy-makers are required to meet the logistical challenges of supporting those who arrive. This pressure has grown as waitlists for asylum hearings and for the deportation process increase, and the widely publicized conditions in American detention centres causes Canadians to look at their own practices.

In many senses, the system still functions. Asylum seekers are processed and municipalities, provincial governments, and regular Canadians – both personally and through NGO’s and charities – have stood up to help. In Montreal alone, the Catholic Church has set up shelters to house asylum seekers and refugees, and NGO’s run a variety of initiatives— from jobs training to help match asylum seekers’ skills to the Canadian market to legal support for those in detention centres. In Ontario, smaller municipalities are hosting asylum seekers so that costs and benefits of new arrivals are spread more evenly. The government has also taken steps to adapt: NGO’s have been consulted on the system’s flaw, a surge of hiring has occurred to handle cases, and the process for work permits has been expedited so that asylum seekers don’t sit idle.

It is difficult to tell whether or not the Canadian system is successfully adapting, especially as it faces an increasing backlog of cases. Some issues, including the cooperation of provincial governments, are outside its control. Others, such as the Safe Third Party country agreement, remain unaddressed, and changes such as the newly created “Minister of Border Security and Organized Crime Reduction” have been met with as much criticism as welcome. Whatever concerns are had, from how well the government is handling change, to the health and safety of the asylum seekers themselves, it is helpful to know how the system works. The system is complicated, however, considering politicians’ willingness to exploit confusion and their unwillingness to admit faults, public awareness is needed. Concerned observers cannot change the system themselves, however, awareness allows calls for justice – or demands for change – to be directed where they matter most.

[1] Attached is the CBSA’s guidelines for removal orders and how to implement them.

This article is part of a wider series on the Canadian Refugee/Asylum System. For an Interview on Canadian Detention Centres see here.

This article was edited by Alec Regino and Zoë Wilkens