How Education and Statues are Changing the Comfort Women Narrative

How statues and history interconnect for comfort women and marginalized communities

TW: Sexual assault, rape, slavery.

In the contexts of war and conflict, sexual slavery is never absent. For Japan, the country’s imperial past — consisting largely of war and territorial conquest — has hindered positive relationships with neighbouring countries in East and Southeast Asia. In particular, the abuse and sexual assault of “comfort women,” mainly from Korea, but also from China, Philippines, Indonesia, and other countries of Southeast Asia, continues to threaten diplomatic ties, sometimes resulting in severe economic consequences. At a time when most survivors are deceased and the few remaining survivors average 90 years of age, why do these issues generate friction presently?

In the post-colonial context, various levels of the Japanese government have promoted a whitewashed history curriculum about its imperial past, while diplomatically advocating the removal of monuments that refer to it. These measures perpetuate the silencing of sexual assault survivors by trivializing their experiences and encouraging societal forgetfulness, often resulting in inter-generational trauma. Although statues and memorials commemorating these survivors are crucial landmarks for advocacy groups, they constantly face threats of removal due to arguments that they discourage diplomacy and trust between nations. Contemporary anti-colonial and human rights movements, like Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Indigenous sovereignty movements, emphasize the significance of statues and memorials as either tools or obstacles for combatting intergenerational trauma and encouraging responsible acts of accountability. While the uprooting of monuments depicting oppressive, colonial figures is a mechanism for undermining white supremacy for such movements, comfort women statues are necessary for disrupting revisionist histories of Japanese colonialism, and must therefore be safeguarded to promote collective healing.

The history of the Ianfu

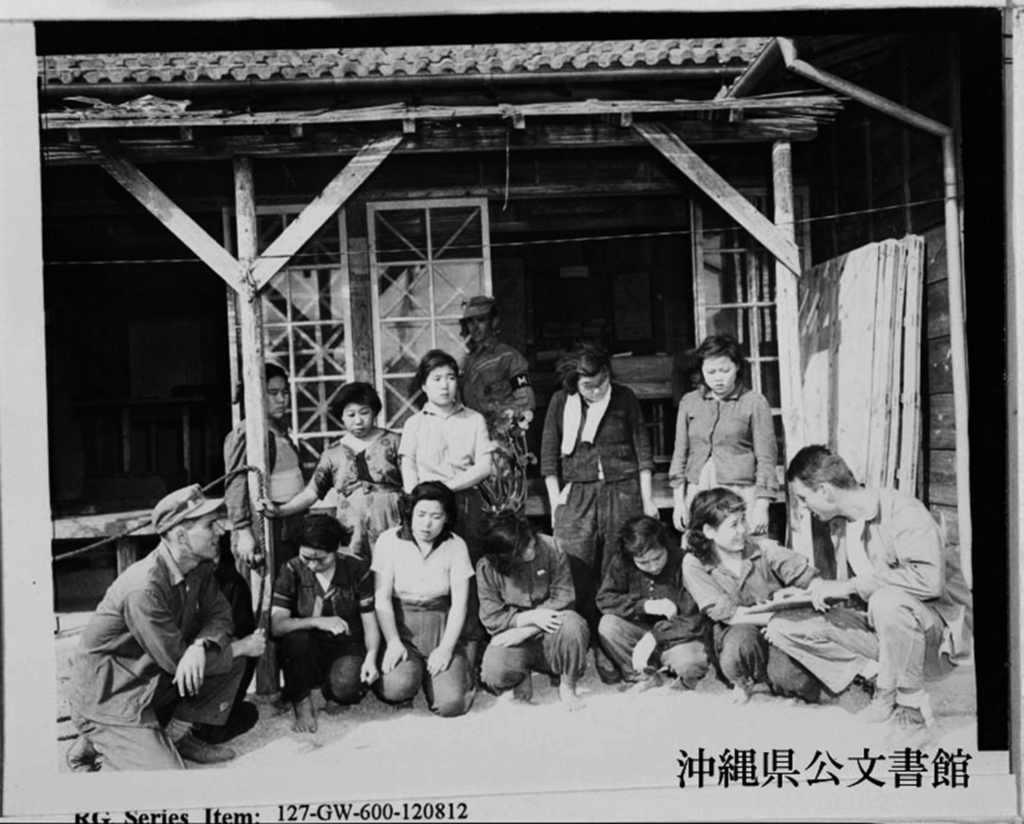

The term “comfort women” refers to more than 200,000 women who served as sex slaves for the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II. Translated from the Japanese ianfu (慰安婦), the title was a euphemism for “sex worker,” that purposefully overlooked the nature of sexual slavery and reinforced the objectification of women. These women were forced, both explicitly and implicitly, to join the military “stations” as large numbers of women were abducted from their homes, sold by their families for money or food, or forced into joining because of starvation. Moreover, many were contained in the “brothels” under the promise of better labour afterward, while some joined under the pretence of becoming a paid nurse for soldiers at army outposts.

The practice and exploitation of sexual slavery are not unique to imperial or colonial regimes; other historically “good” countries have also perpetuated social instability via sexual slavery. For example, following the Vietnam and Korean Wars, the influx of abandoned, half-American “GI babies” reflects the lasting effect of sexual slavery, evidenced by the reckless abandonment of human life. Many of these babies, who were left by mothers who experienced rape, extreme poverty, and trauma, were then adopted by families in the United States and other European countries — the irony of this is not lost. The commodification of mixed-race Vietnamese and Korean war babies in the US begot extreme cases wherein orphanages tricked families into giving up their babies for compensation, then them up for adoption without the mother’s consent. Today, orphanages remain a key destination for voluntourists, thereby perpetuating these effects beyond the war-affected generation.

Curriculum and statues as anti-colonial weapons

Whether through education or memorialization, historical education is a key component in determining if oppression will continue, or if there is fertile ground for reconciliation and progress. Just as sexual slavery keeps populations under control, the normalization of sexual slavery in historical education successfully keeps dissent at bay by invalidating survivors’ pain. This constant invalidation leads to intergenerational trauma and systemic oppression, felt by victims and descendants. This trauma is compounded by lacklustre or nonexistent attempts at retribution, causing persistent rifts in the relationship between nations and peoples.

Former colonies and survivors continue to challenge past war crimes, shifting dynamics and geopolitics within the region as a result. For example, after a Korean Supreme Court ordered two Japanese companies compensate Korean forced labourers for wartime labour, a massive South Korean boycott movement of Japanese products motivated Japan’s removal of Korea as a whitelisted trade partner. During the height of tensions in August 2019, a poll conducted by the Asian Institute for Policy Studies revealed that Koreans had an “all-time low” public view of Japan and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at 1.1 out of a possible 10 favorability points.

Unresolved or under-addressed wartime history is a point of contention for other former colonies as well. For centuries, education has been at the crux of many disputes between colonial countries. Retelling history is a momentous process for affected groups because it allows them to re-illustrate colonial narratives and empower themselves. In 1982, the Japanese Ministry of Education requested whitewashed accounts of Japanese colonial history, replacing terms like “invasion” with “advancement.” In response, Chinese and Korean civil society paired with their respective governments to push for the “Neighbouring Country Clause,” mandating that Japanese history textbooks “show understanding in their treatment of historical events involving neighbouring Asian countries.” Similarly, when a group of far-right Japanese nationalists published a textbook blaming the war and occupation on colonized peoples in 2001, Korean grassroots organizations linked the incident to a larger societal problem in need of redress: the silencing of historically marginalized groups.

Another important method used to challenge the status quo involves memorializing survivors with statues. Statues are not only memorials, but a way to re-tell history from an anti-colonial perspective. For instance, the Japanese embassy in Hong Kong requested that Chinese and Korean comfort women statues in front of the embassy be removed. In South Korea, a private park unveiled a statue collection featuring a comfort woman sitting on a bench accompanied by a man bowing before her. Given the country’s traumatic history with sexual slavery and colonialism, many assumed it was a memorial honouring the survivors’ strength and resilience, as well as a painful reminder of the need to hold perpetrating governments accountable. Such statues are not uncommon; other examples include a golden statue of a comfort woman sitting in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul, and a “statue of peace” depicting Korean comfort women in San Francisco. However, each statue elicited significant pushback from the Japanese government. One of the main arguments made against such statues claims that they are counter-progressive to achieving peace and trust between the countries. Case in point, the mayor of Osaka terminated San Francisco and Osaka’s sister city relationship after the memorial was erected, claiming it was “historically inaccurate,” while the statue of the young girl in front of the Japanese embassy in Korea incited diplomatic threats. This most recent statue is no exception: PM Abe’s government interpreted the bowing man to be Abe himself, and threatened diplomatic retaliation in return.

BLM and other anti-colonial movements have empowered Black, Indigenous, and other people of color worldwide to replace and remove statues of celebrated slaveowners and pro-slavery lawmakers. The significance of replacing a colonial statue is neatly summed up in a sign placed on a vandalized statue of Egerton Ryerson in Toronto, reading “tear down monuments that represent slavery, colonialism and violence”… and replace them with empowering ones that reflect the survivors. Colonized countries voice their versions of history in various ways, but one of the most important — and controversial — ways is through statues and monuments. Because statues are “as much conceptual as they are material,” they allow viewers to find themselves in the portrayal. So, replacing or erecting new statues personalizes campaigns to rewrite history for many groups, as is the case with the comfort women statues.

Retributions are still being demanded, and anti-colonial movements remain a powerful force to this day. However, many activists are now turning towards education as their first line of defence — even the curriculum taught in foreign countries is a target of change. And though numerous attempts of reconciliation have been made in the past to absolve such tensions, the controversial stance towards statues and the discomfort with direct confrontation presents a wider problem of attempting to encourage forgetfulness and forgiveness in light of historical injustices.

The relationship between statues, comfort women, and other anti-colonial movements is clear. As the global political climate of international relations continues to shift, post-colonial narratives are increasingly open to amplifying the voices of survivors’ descendants and affected populations. With this in mind, we must then ask ourselves: will compensation in any form truly help absolve intergenerational trauma and allow for stronger relations? And if so, how much is enough? Just as issues relating to comfort women have permeated inter-state views — extending to sanctions and broken alliances — if anti-colonial movements are ignored, marginalized voices will continue to be silenced.

Featured image: “Peace statue comfort woman statue 위안부 소녀상 평화의 소녀상 (3)” is Public Domain via Flickr.

Edited by Emma Frattasio