How Social Media Divides Us

In recent years, social media has both instigated and bore witness to new divisions in our society. Even though octogenarians manage to use it, social media is a complicated digital tool, involving precise and hidden mechanisms that interact behind our telephone’s touchscreens. The occasionally arcane nature of social media platforms and the business models in which they operate leads to political polarization, divisions, and controversies around the world, with some of the most contentious debates occurring in the United States.

The business model

All social media websites and applications, like Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, Instagram, and even LinkedIn, use similar strategies to make a profit. Because social media is free to use, the simple saying “the user is the product” is frequently invoked, albeit with the wrong understanding. More accurately, these platforms sell our attention to their real clients: the advertisers. The more time users spend on the app, the more ads they will see, allowing advertisers to generate revenue, thereby increasing the platform’s profits.

This strategy works. In the fourth quarter of 2019, Facebook generated $21.08 billion in total revenue, most of which came from advertising. This trend is not slowing down either — social ad spending is actually predicted to increase by 20 per cent in 2020. While this business model is not a new development, dating back to the television era, social media provides a much more personalized tool to target users more efficiently. As we interact with Facebook, Instagram, or Youtube, behind-the-screen algorithms gather information on our tastes and preferences to suggest posts or videos that best fit our interests. The personalized nature of social media feeds a large part of why the average person spends up to three hours a day on social media.

Even though 44 per cent of Americans use Facebook as their primary news source, social media companies regularly reject the title and responsibilities of “media companies,” sidestepping their legal obligations to moderate posted content. Consequently, users who typically engage with conspiracy theories are more likely to come across conspiratorial news in their social media feeds. In the case of the Pizzagate conspiracy theory, Facebook’s recommendation engine presented conspiracy-minded users with suggestions to join Pizzagate groups, further spreading the rumour that Bill and Hillary Clinton were running a pedophile ring from the basement of the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria in Washington DC. The conspiracy theory attracted so much attention online that one man ultimately decided to enter the restaurant with a gun and fire at one of the restaurant’s employees.

Political consequences

As events like Pizzagate demonstrate, platforms will show users what they want, no matter the validity of the content. This function is more or less harmless when talking about food or video games, but it becomes much more problematic with topics pertaining to ideological beliefs and politics.

Social media creates what is known as echo chambers. Echo chambers are settings where interactions between like-minded individuals result in the amplification of their mutually held beliefs and preferences. On social media, the users confirm their pre-existing political beliefs by communicating with other users who share their political views. Arguments from the other side of the political spectrum do not appear on the user’s feed, insulating individuals in a personal ideological bubble.

Echo chambers and political polarization also lead to increased political partisanship. With exterior opinions consistently confirming individual beliefs, voters are more prone to vote for a party than an individual while holding “very unfavourable views” of the opposing party. These partisan feelings are especially visible during election years and political debates. For example, in 2016, 92 per cent of Hillary Clinton’s voters believed she had won the second debate, while 61 per cent of Donald Trump’s supporters said the same about their preferred candidate. Both Trump and Clinton supporters rated their candidates more positively, illustrating strong partisan inclinations in both parties.

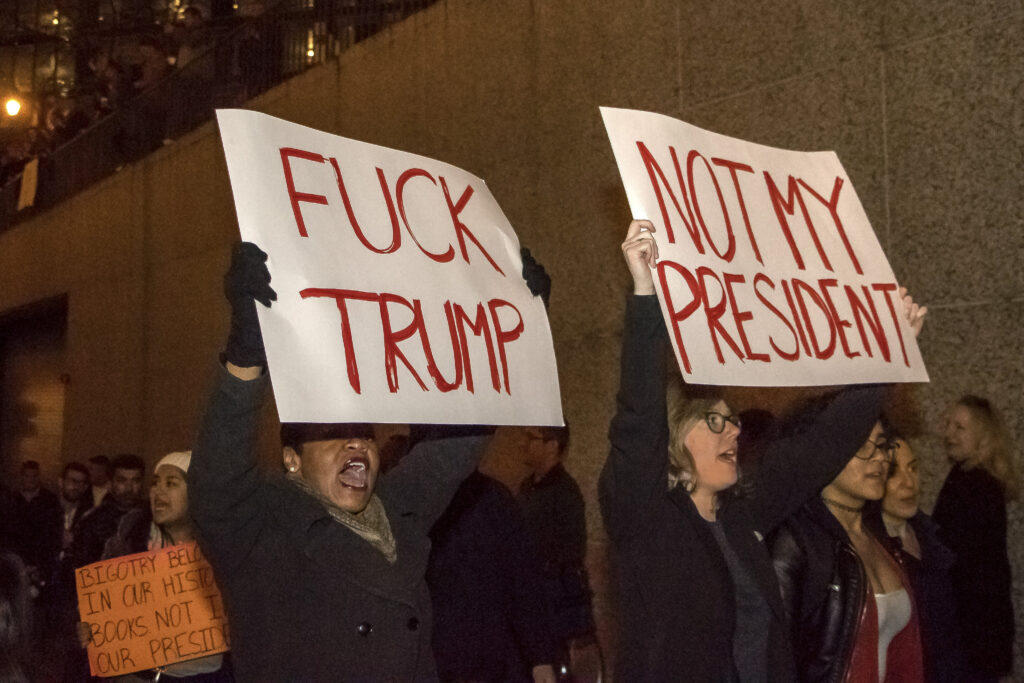

Today, ideological surveys show that political polarization is at a twenty-year high, with Democrats and Republicans more divided than in the past. This cleavage not only signals increasing partisanship but also rising antipathy and hostility towards the opposing party. Anger is now motivating people to vote, reinforcing the phenomenon of “negative partisanship.” This sentiment was especially strong in 2016, wherein most voters held unfavourable views of the opposing party’s candidate, whether it was Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump.

By perpetuating political polarization, negative partisanship is now widely understood and used during elections, entrenching the demonization of political actors with opposing views. Donald Trump is a prime example of this trend, evidence by his abundant use of social media platforms, namely Twitter, to vilify his enemies. Much like political polarization, Trump’s tweets promote and bolster close-mindedness, antipathy, and hatred.

It is not a coincidence people who are on social media are called “users.” Much like drugs, many are addicted to their feeds, likes, and posts. While the consequences are not direct illness or death, social media divides and separates society by spreading conspiracy and contributing to political polarization. If left unchecked, social media users may soon find themselves in rehab.

Featured image: “Like” by afagen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Edited by Luca Brown