How the Far-Right Captured the Young Vote in Poland

Since October 30, thousands of women in Poland have flooded the streets of Warsaw, protesting against the unrepealable Constitutional Tribunal ruling outlawing nearly all abortions. The current government’s resolve to restrict women’s bodily autonomy is only one of many divisive issues in the polarized Polish political sphere. The abortion law reflects a broader rise in support for the traditional, heteronormative, and exclusive “Polish family model” that the ruling, ultra-conservative Law and Justice Party (PiS) promoted in its last campaign. The more curious trend, however, is the capture of the young vote by the PiS and the radical right-wing Konfederacja, indicating that a lack of collective memory among millennials and Gen-Zers has made way for nationalist populism.

The PiS emerged in 2001 as the coalition of a Christian right-wing political party and a conservative centre-right party. The party appeals to its traditional base through conservative social policy stances, such as anti-abortion values and LGBTQ+ intolerance, as well as heavily promoting the traditional family model, all the while using liberal economics to appeal to a wider group of voters. It has struck a chord among young voters in particular through its liberal “Home Plus” program, which addresses the housing crisis for young low-income families.

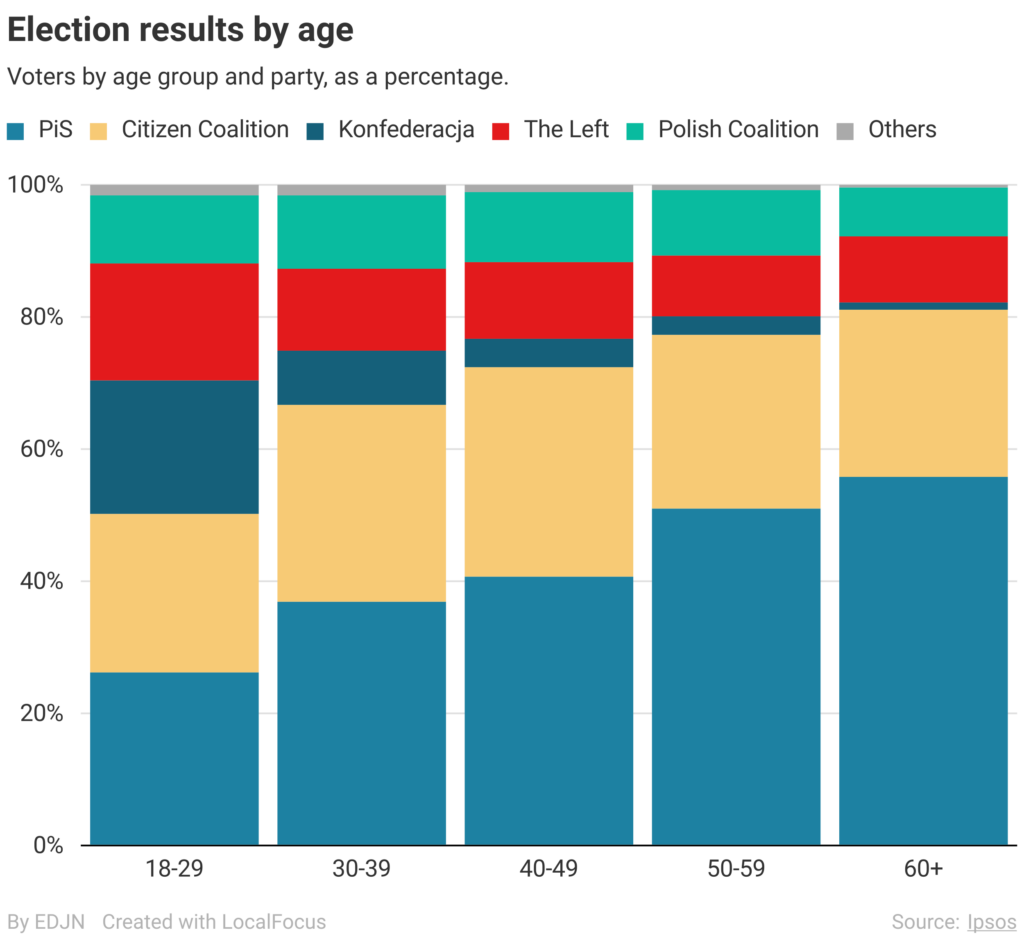

By marrying its conservative ideological push of the Polish family model to the liberal economic policies of the “Home Plus” program, the PiS garnered support across traditional fault lines of gender and age, winning a record percentage of women and young voters in 2019. Not only do the headlining economic policies specifically benefit young people, unprecedented support for the alt-right party, Konfederacja, suggests that anti-LGBTQ and anti-feminist rhetoric is highly successful among voters under 30. For example, Konfederacja, which promised “anti-LGBT legislation” and no state protections to so-called “deviant LGBTQ+ individuals” during pride parades and demonstrations, polled most successfully among 18-29 year olds. Indeed, 20 per cent of young Poles voted for the Konfederacja, more than double the percentage from any other age group. Despite the ideological inconsistencies within the PiS platform, research suggests voters are ideologically inconsistent themselves, and ultimately tend to prioritize their individual economic well-being over collective social progression.

Graphic showing Poland’s 2019 election results by age. “Election results by age” by EDJNet is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

While the liberal economic policy and conservative ideological push of the PiS would not intuitively mesh for policymakers, what links them is a set of authoritarian tendencies that threaten democracy in Poland. For much of its existence, the modern Polish state has been under authoritarian rule — and this history sets a precarious precedent not only for democratic backsliding, but also for a persistent openness to authoritarianism within its political sphere.

During the interwar period, Poland was ruled by the Sanacja, which claimed power in 1926 after a coup d’état led by Józef Piłsudski. Under the Sanacja, an odd coalition of left, right, and centre parties, whose main goals were allegedly eliminating corruption and minimizing inflation, the parliamentary democracy model was dismantled. Despite their self-proclaimed non-partisan, non-political nature, their rule entailed government-controlled media, a narrative of nationalistic healing, and the elimination of opposition parties — eerily similar to the current Law and Justice Party’s undemocratic reforms. Even with the Round Table Accords of 1989, which enshrined the principles of separate powers, right-wing parties have consistently challenged the concept’s relevance. The PiS is no exception, having explicitly rejected the Round Table Accords and called for consolidated executive power in order to improve Polish national unity.

Since 2016, the PiS has begun to consolidate its power by controlling media and degrading the independence of its judicial branch. For instance, in 2016, the PiS installed Jacek Kurski, a high-ranking politician within the party, to be the chairman of a leading public television station, the TVP. Since then, dozens of reports from current and former TVP journalists and executives have noted the media company’s purposeful neglect of PiS scandals and an affinity for airing pro-PiS voices. Furthermore, in 2017, the PiS attempted to purge half of Poland Supreme Court justices by introducing a law that would lower the mandated retirement age; when this failed, it took over the National Council of the Judiciary, a body solely responsible for appointing Supreme Court justices, and outlawed complaints by judges against this new process. Subsequently, in 2019, the party was criticised by several European Union officials for disregarding the rule of law, degrading the independence of Poland’s judiciary, and expanding government control of the media to silence the opposition.

Clear parallels can be drawn between Poland’s history of authoritarianism and its current government. As shown by the overwhelming support from young voters for the PiS and Konfederacja, there is a lack of collective memory about Poland’s time under an authoritarian regime. Critically, the missing memory of Poland’s brushes with authoritarianism has led to a young electorate that is unaware of the pernicious extent of the PiS’s threat to democratic values. The re-written narrative by the PiS that communism was only defeated by strong authoritarian regimes has led to an electorate unfearful of restrictions on media and unaware of the impact of degrading separate powers. In contrast to the older generation, which can recall the long battle for democracy, young voters take democratic rights as a given, and have consequently taken an interest in the nationalistic rhetoric of the PiS which promises to prioritize their interests.

But it might not be too late for progressives to win over the young electorate. The PiS won by a far narrower margin in October 2019 than it did in previous years and lost control of the Senate, which means slower policy implementation. Left-wing parties have been able to regain some power through collaboration, voting on policy issues as a unified bloc, and clarifying the narrative of the left as focused on rebuilding democratic institutions. Additionally, the European Union’s critiques of the party’s disregard for the rule of law and democratic institutions have increased momentum for the opposition to more aggressively pursue pushback against the PiS’s threats to democracy. For now, not all is lost: the restrictive laws on abortion are being delayed by mass pro-choice protests and the party’s grip on mainstream media channels is slipping as opposition parties have found the support of private media companies. Most crucially, the government’s attempts to silence protesters has awoken much of the Polish electorate to the authoritarian tendencies of their current ruling party. With the continued organized collaboration of the left, perhaps the young electorate can be persuaded to vote for democracy ahead of their immediate interests in the next election.

Featured image: “Nationalist anti-gay protesters during the Equality March in Kraków” by Silar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Edited by Juliana Riverin and Sara Parker