“I Like to Obey the Law”: Trump and International Humanitarian Law

Speaking to a group of police chiefs in October 2019, President Trump addressed the American presence in Syria, declaring, “we’re keeping the oil—remember that.” As tensions rose in Iran this January, Trump tweeted that his administration had already identified 52 sites significant to Iranian cultural heritage as potential military targets. Both of these comments resulted in immediate backlash from legal experts and were quickly backtracked by senior members of the Trump administration. The comments sparked outrage as they reflected what would be clear violations of international humanitarian law (IHL), also known as the law of armed conflict.

IHL, broadly, is understood as a set of rules that aim to limit the violent impacts of armed conflict. The Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols form the core of IHL. Nearly every state in the world has agreed to be bound by the Geneva Conventions, and many provisions of IHL are now considered to be part of customary international law, which are considered binding on all states.

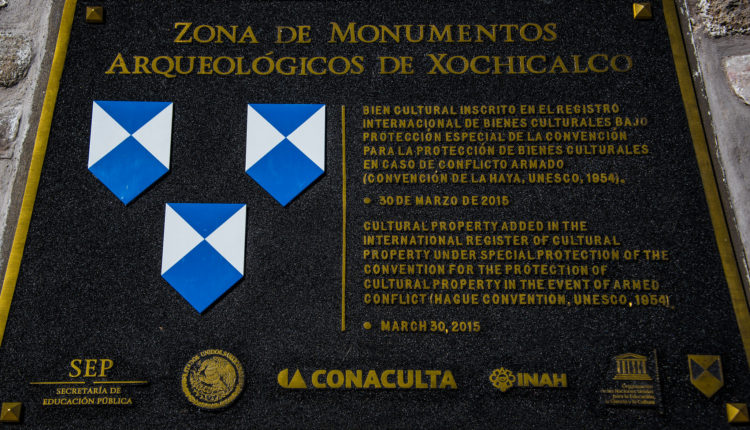

The Conventions and Protocols work to protect all of those who are not taking part in hostilities, or who are no longer participating in hostilities, such as civilians, aid workers, and wounded or sick soldiers. Other agreements also prohibit the use of certain military tactics and weapons, including the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and the 1997 Ottawa Convention on anti-personnel mines.

IHL applies only to instances of armed conflict. It is in effect once a conflict begins, and applies to all parties equally, regardless of who instigated the conflict. IHL does, however, distinguish between international armed conflicts and non-international armed conflicts. A broader range of rules apply to international armed conflicts, which involve two or more states. In non-international armed conflicts, a more limited range of rules apply, as outlined in Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II. While IHL shares many of the same aims with international human rights law, there are important differences in scope of application and the bodies responsible for implementation.

Trump’s comments in relation to “keeping” Syria’s oil and targeting cultural sites in Iran are not the only instances where Trump’s relationship with IHL has been criticized. In 2019, Trump controversially pardoned two army officers accused of war crimes and restored the rank of the third. The legality of the targeting of General Qasem Soleimani under international humanitarian law also continues to be debated.

These two instances were, however, particularly jarring as they reflected actions clearly contrary to IHL. After originally directing US forces to withdraw from Syria, Trump changed course and instructed US forces to secure oil fields in southeastern Syria and mused that the US would be “keeping the oil” in Syria to minimize the cost of the US presence in the country. Experts argued that these actions may be considered pillaging under international law, as prohibited by the Fourth Geneva Convention. James Graham Stewart, a law professor at UBC, argued that if US forces were to secure the oil to protect it for its true owners, these actions may be permissible under international law. However, if US forces were to take the oil without the consent of its rightful owner, this would be a war crime. The oil is considered state-owned property in Syria.

On January 4th, Trump tweeted that the US had identified 52 Iranian sites “some at a very high level & important to Iran & the Iranian culture” as potential targets in escalating tensions with Iran. These actions would have been a war crime under the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. This Convention was adopted in the aftermath of the cultural plundering committed by the Nazis during WWII, and was ratified by the US in 2008.

While Trump ultimately backtracked from his two statements, Trump’s comments reflect contemporary debates surrounding IHL. Following 9/11 many people, especially in the US, questioned the continued relevance of IHL. The Bush administration crafted a new category of “unlawful enemy combatant to apply to members of Al Qaeda and the Taliban, alluding that those who fell within this category fell outside of the law. The Bush administration also led efforts to reverse long-standing prohibitions against actions such as torture, likewise seeking to redefine torture.

Others have questioned the effectiveness of IHL when breaches have frequently occurred. The targeting of cultural sites, for example, has occurred previously in conflicts such as Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, and Syria. Contemporary debates also continue surrounding technologies such as drones, robots, and autonomous weapons, as well as the urbanization of conflict, the rise of asymmetrical warfare (such as between the US and ISIS) and the use of illegal tactics to undermine stronger opponents have led to the continued question of the relevance of these rules to modern conflicts.

While violations of IHL might be frequent, some point to state efforts at concealment, justification, and remorse as evidence of the legitimacy of IHL. Many, including UN humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock, believe that a solution lies in better enforcement efforts. The ICRC has criticized negative discourses surrounding the respect of IHL, arguing that risks creating an environment where violations are considered acceptable. Writing in “International Humanitarian Law: Theory, Practice, Context,” scholar Daniel Thürer argues that IHL has frequently evolved to address modern challenges, albeit often after calamitous events, such as the creation of the Geneva Conventions following the Second World War.

For those who fear the irrelevance of IHL, Trump’s words may offer some mild comfort: “And you know what, if that’s what the law is, I like to obey the law.”

The featured image, “Trump speaking with supporters at a campaign rally at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona” is attributed to Gage Skidmore. This image is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Edited by Elizabeth Hurley