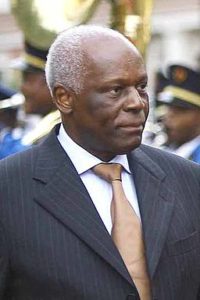

Combating Corruption: The Insidious Influence of Jose dos Santos

The incumbent president of Angola, Joao Lourenco, is no stranger to politics. Born in Portuguese Angola in 1954, he joined the anti-colonial struggle for independence as a member of the MPLA. After the Portuguese ceded Angola in 1975, he traveled to the Soviet Union and became educated in anti-colonial and socialist teachings. Upon his return to Angola, he quickly rose through the ranks of the MPLA’s elite. His different roles included governor of Moxico (Angola’s largest province), deputy speaker of the National Assembly, and, most recently, Secretary of Defense. Lourenco’s political ambition did not go unnoticed by Jose dos Santos, who claimed Lourenco to be his successor for the Angolan presidency.

Despite the fact that the majority of Angolans voted for the MPLA, as has been the case in every election, the party lost seats in the National Assembly to UNITA and other minority parties. The message is clear: Angolans are looking for real change. Lourenco marketed himself as the candidate that would ensure accountability for the government: he promised to end the cronyism and corruption that have resulted in the Angolan government “losing” US$4.2 billion between 1997-2002, roughly equivalent to the amount spent on humanitarian aid in the same amount of time.

However, the question of Lourenco’s ability to enact lasting change is compounded by the fact that dos Santos maintains a lasting control over state affairs and the economy. Prior to retiring, dos Santos ensured that his interests would be met in spite of the new government: he signed a decree freezing military, security, and intelligence appointments until 2025. This ensures that his allies and friends will maintain influence over the government and military affairs; Lourenco is powerless to stop him. To further guarantee protection from prosecution, dos Santos has appointed himself President of the Republic Emiritus Honorary. This impunity, which will also be enjoyed by dos Santos’ family and friends, raises the question of whether the concept of ‘government accountability’ will see fruition.

Another sphere of influence for dos Santos and his family is the economy. Jose dos Santos appointed his daughter, Isabel dos Santos, to the head of Sonangol, the state-owned oil company. She also maintains a 25% stake in Unitel–the country’s largest mobile service provider–and 42% of Banco BIC, Angola’s largest private bank. Many of dos Santos’ children, cousins, and friends have benefitted from their connection to the former president; this allows them to earn money from the state and maintains dos Santos’ influence over various sectors of the state. There actions are known as “neo-patrimonialism“, in which state resources are used to secure loyalty. Neo-patrimonialism is endemic to corruption since those benefiting from this patron-client relationship are often reluctant to side against their patron. In this case, many of the dos Santos stalwarts remain in office and will continue to influence the economy to the benefit of their former benefactor. Furthermore, in the absence of these neo-patrimonial benefits, they are unlikely to support any anti-corruption policies that may limit their profits.

Despite Joao Lourenco’s claims that Jose dos Santos would wield no influence in his presidency, the fact remains that dos Santos’ cult of personality continues to have considerable control over the state, military, and economy. The presence of dos Santos loyalists in influential governmental positions also ensures remnants of the old order.

In the last four decades, corruption, nepotism, and neo-patrimonialism have been the form of social trust networks for the Angolan government. For Lourenco to successfully achieve his task of stabilizing the government, he will have to undergo substantial reforms of the political and economic institutions of Angola. This will include increasing transparency and accountability to allow citizens to rebuild faith in the government.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi