InSite Vancouver: A Road to Recovery or Back Down the Hole?

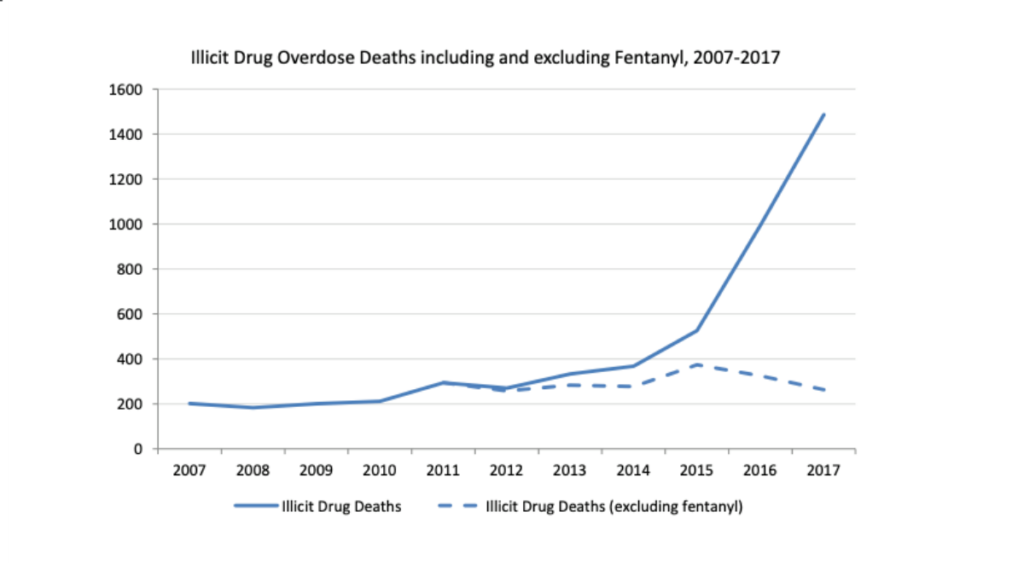

The introduction of fentanyl into the drug supply, which the BC Coroners Service holds responsible for the major spike in overdose deaths, has exacerbated the already prominent drug and poverty issues plaguing Vancouver and British Columbia. In the face of the seemingly ever growing calamity, InSite, the first supervised injection site ever opened in North America, has become a beacon of hope for the city. Promoted as a more humane and progressive response to drug use and addiction, InSite has become a mainstay in Vancouver’s response to its drug crisis, leading other cities, including some in the United States, to follow suit. However, despite the city’s acceptance of the program, deaths continue to mount and the crisis seems to have no end in sight. Its history and effectiveness remain relatively unknown to the general population, begging the questions, what exactly is InSite, and does it actually work?

The Current Crisis

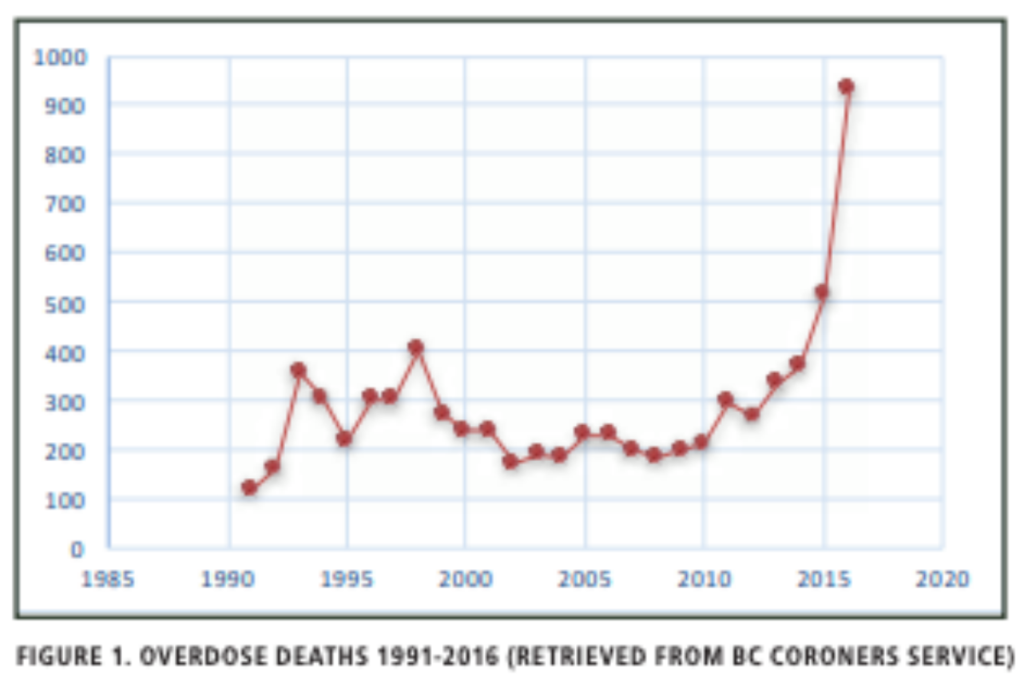

Already burdened with a history of rampant drug abuse, 2018 saw Vancouver set new records in overdose deaths, as the city has struggled to find an effective and timely solution. According to a report from the BC Coroners Service, overdose death rates following 2003, the year of InSite’s inauguration, began to generally increase, though they remained well below the deaths during the 1990’s crisis, which peaked in 1998 at 400. The same report indicates a major spike starting in 2012, though this is the year attributed specifically to the emergence of fentanyl in the drug supply. Following the province’s declaration of a state of Public Health Emergency on April 14, 2016, overdose interventions (treatments of overdoses) skyrocketed from 30 to 240 a month (eight cases a day). Between 2008 and 2018, provincial overdose deaths increased from 183 to 1,489. Vancouver, specifically, saw a significant increase over the decade, experiencing only 38 overdose deaths in 2008, while 382 occurred in 2018. Moreover, Vancouver has consistently led the province in total overdose deaths as well as rates of overdose deaths per 100,000 residents. In an analysis of the locations of Vancouver overdose deaths in 2018, 45% occurred in private residences, 33% in social housing, and not a single person died from an overdose at any of Vancouver’s safe injection sites. With death tolls continuing to rise in the face of InSite’s supposed success, one begins to wonder what effects InSite truly has and whether it goes beyond merely providing a safe space for users.

The History of InSite

The idea of introducing a safe injection facility to Vancouver took root in the early 1990’s, when overdose deaths among injection drug users reached, at the time, record levels. In 1997, PHS Community Services Society decided to take action, organizing a conference in Oppenheimer Park, a centre of poverty in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES). The DTES, itself, has “[become] synonymous with poverty and addiction” as a result of the 1990’s drug crisis and remains the most clear example of Vancouver’s inequality. The conference, Out of Harm’s War, brought speakers from around the globe to present new options for managing drugs, addiction, and crime plaguing the city. Though the conference did not result in any major breakthroughs for PHS, the organization continued to lobby for more progressive responses to the city’s growing drug and poverty problems. In February 2003, PHS planned on creating “Health Quest,” a rented space that would be used as a safe injection site, funded by private donations and operated by volunteers. The project garnered support from all levels of government, leading to the creation of InSite, the first safe injection site in North America, on September 2003. While the site enjoyed government support at its inception, the Conservatives’ arrival as the ruling party led to a major legal battle concerning its future.

The Conservatives’ assumption to power created juxtaposing approaches to handling drug use and addiction. The new federal government, maintaining a more traditional hard-on-drugs stance, stood in direct opposition to the provincial and municipal governments’ attempts to strive for harm reduction strategies. When the issue was taken to court, the BC Supreme Court initially ruled in favour of InSite, but following numerous appeals from the federal government, the case ultimately fell into the hands of Canada’s Supreme Court. Ultimately, all nine Supreme Court Justices ruled against the federal government on the basis “that attempts by the country’s Conservative federal Health Minister to close InSite contravened the country’s Charter of Rights by threatening the lives of injection drug users.” Drug addiction was thus designated as “an illness for which Canadians have a right to treatment.” As a result, InSite has become a mainstay in Vancouver’s attempts to manage addiction and drug use. InSite was viewed as such a success that a second supervised injection site, Powell Street Getaway, was opened in July 2017. The growing crisis has also forced the creation of six pop-up “overdose prevention sites,” smaller scale versions of InSite scattered throughout the DTES and some Vancouver suburbs.

InSite By The Numbers

Though InSite has its share of supporters and critics, the service has become a major part of Vancouver’s DTES. Based on statistics from Vancouver Coastal Health, 3.6 million people have utilized the facility since its inauguration in 2003, with InSite itself estimating roughly 700-800 visits per day. Moreover, it has received 48,798 clinical treatment visits while intervening in 6,440 overdoses without any deaths.

How InSite Works

With a primary goal of preventing deaths, InSite provides its clients a safe space to use drugs under the supervision of nurses and trained staff. Thus far, they have achieved this goal and not a single person has died under the watch of InSite since its opening. While on the premises, users are provided support from staff and clean equipment in order to reduce transmissions of disease and infections.

However, there is a noticeable lack of care given beyond providing this space. InSite’s website states that “staff can… refer participants directly to OnSite, a… detox and treatment program… located right above the supervised injection site.” While this option is available, allegations have emerged that InSite has failed to provide anything more substantial than providing users a safe space to use drugs. An opinion piece from the National Post alleges that due to InSite’s aim at being “low barrier,” its staff hold back on suggesting rehabilitation and other addiction treatments out of fear of alienating patients and potentially pushing them back to using on the streets. Moreover, it has been claimed that staff have begun requiring stress leaves due to clients failing to utilize the rehabilitation and addiction treatments available to them, putting into question the true extent of InSite’s impact on the resolution of the current drug epidemic. Still, InSite cites numerous studies advocating that the positive benefits go beyond just a safe space: reduced overdose fatalities, improved addiction treatment initiation, and increased savings in public health funds. In a 2008 study on the effects of supervised injection sites, Health Canada found reductions in overdose mortalities, ambulance calls, and transmissions of disease, though its effects on hospitalizations remain unknown. More importantly, it asserts that its benefits are limited by its size constraints. When the University of British Columbia assessed the facility, InSite was associated with improved rates of commencing addiction treatment, decreased injecting at the site itself, and an increase of over 30% in detoxification service usage.

Critiques of InSite

While InSite enjoys an overwhelming amount of support, it is not without its detractors. Dr. Colin Mangham, who worked extensively in drug prevention for 37 years, stated that he was “shocked at how weak” the assessments regarding the successes of InSite turned out to be. Specifically, Mangham criticized InSite’s claims to have reduced fatal overdoses, stating that the results had been subject to interpretation bias: the ones who created the program also conducted its assessment. Joining his skepticism, retired Vancouver Police Department (VPD) inspector John McKay, who was assigned to Vancouver’s DTES, described the heightened police presence in the area around InSite after its opening as “integral” to its reduced overdose rates. Moreover, though InSite claims to have reduced crime in its immediate vicinity, VPD statistics indicate that crime in the DTES as a whole increased between 2002 and 2016. While InSite alleges that it has led to increased treatment for addiction, a 2006 study from the British Medical Journal that analyzed the years before and after InSite’s opening discovered “no substantial decrease in the rate of stopping injected drug use.” According to Tristin Hopper of the National Post, there has been no conclusive, long-term data that affirms InSite’s claim that the service helps drug users quit and begin the path to recovery. Hopper, in particular, questions two studies InSite cites as support for this claim, stating that they only “cover a limited time period, and only document an increase in admissions to detoxification.” To make matters worse, a large percentage of Vancouver DTES drug users rarely utilize safe injection sites, with some deciding to use their drugs right outside InSite’s building.

Looking Forward

While Vancouver health officials continue to support the work of InSite, they do recognize its limitations and the need to go beyond simply a safe space. Still, it would be unfair to fault solely InSite for the upsurge of overdose deaths in recent years. The continued ubiquity of poverty, addiction, drug use, and a host of other problems in Vancouver’s DTES continue to be major barriers to recovery and treatment. It has become almost inevitable to relapse in such an arduous environment. And with the source of drugs continuing to come from the black market, products will be laced with fentanyl. Furthermore, the overprescription of highly effective pain-reducing synthetic opiates has helped amplify the crisis to its current state.

As it stands, the drug crisis remains a mainstay in Vancouver and British Columbia. InSite has stood strong in the face of such a catastrophe, yet without any definitive steps beyond providing a safe space, it becomes valid to ask whether it is simply enabling users without providing a proper path to recovery. While the intentions are surely altruistic, it appears on the surface to be another empty policy enacted by officials to look progressive. It is even worthwhile to question the message sent to the general public that hard drugs remain illegal and stigmatized, yet safe spaces are provided to use those very same substances . With Toronto’s chief medical officer calling for the decriminalization of all drugs, perhaps legalization and the undercutting of the current black market could reduce the amount of impure and dangerous drugs landing in the hands of the population and also lead to proper care and treatment for those battling addiction.

Ultimately, it is clear that InSite, at the capacity it is currently working, is at best a band-aid solution and at worst enabling an epidemic that has plagued Vancouver and British Columbia as a whole for years. If Vancouver and the rest of the province truly do believe in supervised injection sites, major investments in expansion are required to meet the current crisis head on. More importantly, InSite and any other supervised injection sites must place more emphasis upon funnelling users towards rehabilitation and treatment in order to keep them from becoming another statistic.

The Opioid Crisis, along with poverty and homelessness, remains a stain on ‘Beautiful British Columbia.’ For a place that prides itself on beauty and progressive, liberal values, the entire province, and Vancouver in particular, must take substantial steps towards addressing the horrors they currently face. It is clear that the problems, and the drugs that have caused it, will not just fade away. The time for alienating or vilifying addicts and users has passed. Though InSite and supervised injection sites are steps towards progressive and humane solutions to the current crisis, the government and population as a whole must stand in solidarity with those going through their struggles and continue to push for solutions that lift them up and enable their returns from the margins.

Edited by Helena Martin