The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia Comes to an End: What Now?

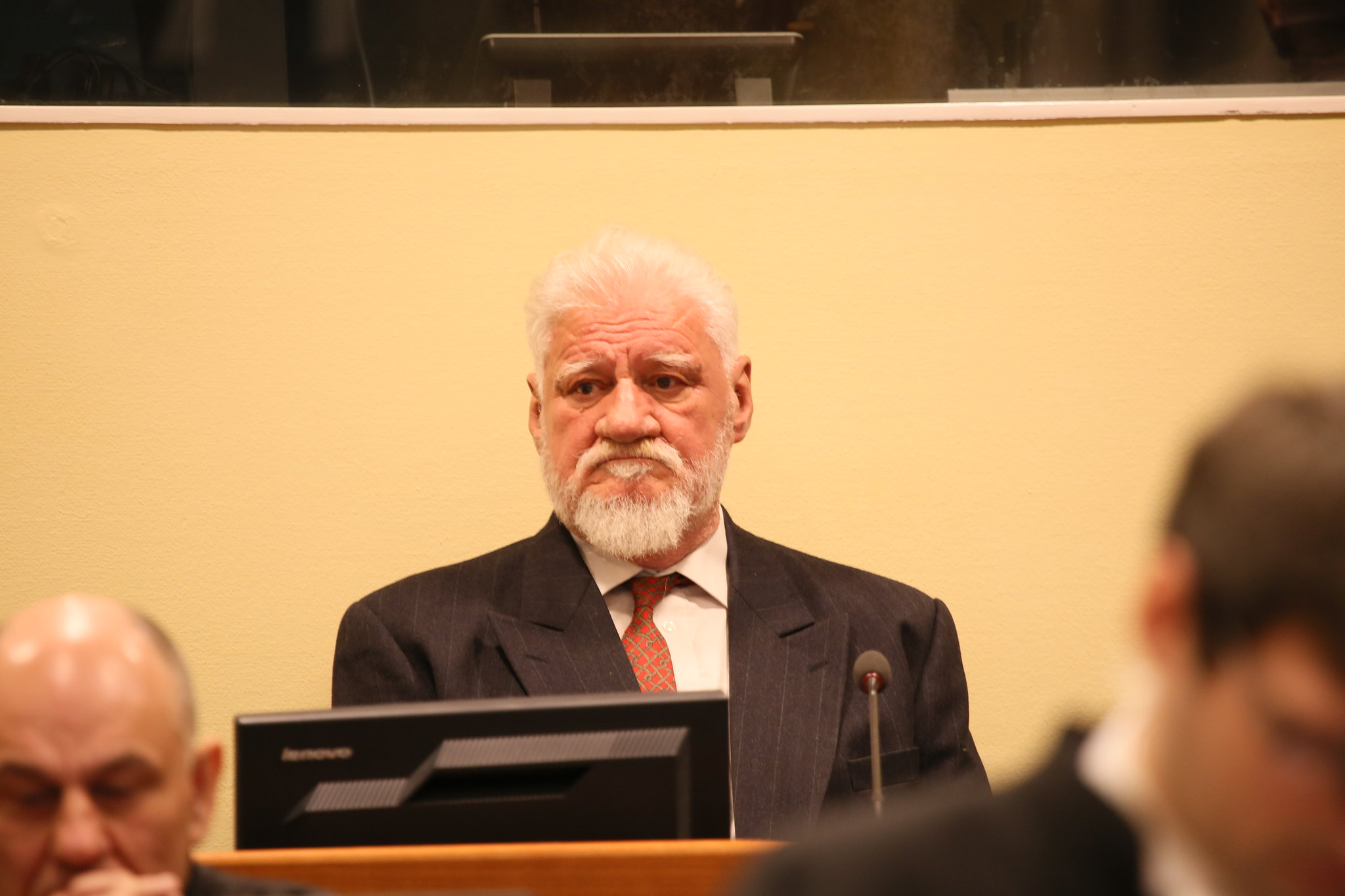

“I just drank poison” — With these words, the twenty-five-year mandate of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) came to an abrupt end. The words, last spoken by former Bosnian Croat General Slobodan Praljak, marked the end of a quarter century of agony, closure, and disappointment for those it was intended to serve. The ICTY’s legacy is not easily discerned. On December 31, 2017, when the court will finally close its doors, the dissolution of Yugoslavia will reach its symbolic ending. What are we left with once the doors of this questionable institution shut tight? If you ask the people it affects the most, their responses will vary from case to case. After twenty-five years of injustice-infused justice, the picture seems no clearer than it was when the court set up in 1993. Certain cases have been duly processed, others let to walk. The internal politics of Bosnia and Herzegovina have long been dictated by the ups and downs of the ICTY. In absence of such a polarizing actor, the country is left with its polarizing legacy. So what now?

With the strike of the final gavel, six Bosnian Croats were sentenced to a total of 111 years for crimes against humanity and joint criminal enterprise. The sentence dealt a blow to the Croatian constitutive minority who now find themselves on the wrong side of history in a country that is ostensibly theirs as well. The convoluted consociational democracy that is Bosnia and Herzegovina is constituted by two political units, the Republika Srpska (RS) and Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), as well as three constitutive peoples: Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs.

The verdict to the “Croatian six” comes at a time of, as per usual, heightened tensions between the three constitutive peoples over constitutional reform and foreign policy. The political apparatus has been stuck in gridlock over a proposed constitutional reform which would enable Croats to fulfill their constitutional right to elect their own representatives. The suggested reform would ensure each ethnic group the ability to elect only from its own constituency. The issue has been a lurking toxicity since 2006 when Željko Komšić became the Croatian Presidential Representative with votes from primarily Bosniak Muslims. Bosniaks — who outnumber Croats by more than three to one — can elect both their own and the Croats’ member of the tripartite presidency. Thus far any attempts to retool the ceasefire constitution (read: Dayton Peace Accords) have been done with great reluctance and often at the intervention of the High Representative, a wartime relic which allows a UN-appointed commissioner to hold quasi-executive powers. Without the proposed electoral reform, the upcoming 2018 elections for Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Upper House will be technically unconstitutional. The Federal Constitutional Court has said it will protect their citizens’ electoral rights, but with the ICTY verdict, it seems unlikely concessions will be made to the Croat minority. Should the legislative bodies not come to a consensus on a new electoral law soon, some fear EU and US intervention might ensue. The European Commission will remain vigilant and monitor hopeful progress.

Several Croat representatives have voiced their concerns with the verdict as they fear the legacy will curb the political equilibrium. History is what the textbooks will read one day. With the “Croatian six” verdict, the legacy of Bosnian Croats switches from one of liberators and defenders to dividers and aggressors. General Praljak’s public act of suicide best portrays the consternation that has met Bosnian Croats. Justice has been served to those seeking it, but they will all be found by more political instability. The ramifications are yet to be seen, but there is no doubt that any progress on constitutional reform hitherto will yet again come to an indefinite halt.

A week before the “Croatian six” verdict, the ICTY sentenced Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladić to a life sentence for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. The former general was found guilty of ten acts of genocide. Amongst the crimes committed by Mladić and his men were the 1,425-day Siege of Sarajevo and the 1995 genocide of 8,373 Bosniaks in Srebrenica. Earlier this year, former Bosnian Serb President Radovan Karadžić received 40 years in jail for the same list of crimes. Both sentences have brought long overdue justice to the thousands affected by Bosnian Serb actions. Those affected can find consolation in the ICTY’s verdicts; however, the verdict will never rebuild their homes, employ their children, or cover their healthcare. So how have the Mladić and Karadžić sentences impacted Bosnia and Herzegovina?

Outside of the confirmation that one side was more guilty for the war than others, there has been little or no change. The billboards in the RS capital of Banja Luka still profess their admiration for the wartime regime with equal fervour. Banja Luka is no more inclined to cooperate with Sarajevo than they were before, nor does Sarajevo have any newfound moral leverage to hold over Banja Luka. If anything the verdict only added fuel to the fire of ethnic tensions as each camp became more entrenched in their thoughts. For Serbs in RS, the verdict was a confirmation that the powers that be are set against them, while for Bosniaks and Croats the ruling was only a paper version of pre-existing opinions. Instead of bringing the country much needed peace and reconciliation, it has had an opposite effect. RS President Milorad Dodik used the Mladić sentence to reiterate his support for the “national hero” and point out the ICTY’s “anti-Serb bias.” For Dodik there is a reason “90 Serbs have been indicted… and on the other side only 9 Bosniaks and 28 Croats.” Unfortunately, reconciliation has become an afterthought in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where nationalist rhetoric goes much further than any actual policy.

It was this said rhetoric that spun the country into another mini-crisis when, in light of the Mladić ruling, Bosniak representative Bakir Izetbegović called for the recognition of Kosovo. The country’s recognition has been a contentious issue in Bosnia and Herzegovina where Bosnian Serbs tow Belgrade’s party line of one united Serbia. In response to Izetbegović’s remarks, Milorad Dodik addressed the nation in an interview for RS television. The Bosnian Serb leader made it clear that should Izetbegović bring Serbia’s territorial integrity into question, Dodik would do the same with Bosnia and Herzegovina’s territorial integrity. Dodik argued that if Bosnia and Herzegovina were to recognize Kosovar independence then RS should hold the right to their own sovereignty as well. This is not the first time Dodik has evoked RS independence.

Last January, Dodik went forward with a referendum on Republika Srpska’s Independence Day. The referendum had been ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and High Representative but was conducted nonetheless. Banja Luka’s evident disregard for the country’s institutions is but a continuation of the very irredentist politics the ICTY stood against when sentencing Karadžić and Mladić. For Dodik and his cronies, the ICTY ruling is nothing but an extended op-ed. Where justice should bring resolution it has bred division.

So where is Bosnia and Herzegovina 20 years after the war and what happens with the country now that war is “behind” them? The ICTY has provided many with minimal comfort and opened the door for those affected by war crimes to seek further justice. Regrettably, the ICTY means very little to many if not most people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. With time the memory of the wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina will fade. Once there are no longer witnesses to correct our historical revision, history becomes not more than words in a book. Future generations will hopefully know these men as war criminals, but in the meantime, they are someone’s hero; a not forgotten emblem of a time when Bosnia and Herzegovina was not a country at peace. When politicized, these emblems can serve a vile purpose for the Machiavellian prince who cares not for international structures and CNN press clippings.

When all is said and done, the ICTY will not stop any group from glorifying their “own” war. In light of this, it is hard to imagine a better tomorrow for the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Unless there is a foundation-shaking change in the status quo, Bosnia and Herzegovina will persist to be the dysfunctional consociational oligarchy it has become. Naturally, no one can expect a couple of court cases to save a country. The underlying issue are the political elites who misuse a vehicle of reconciliation for the purpose of division. Omitting a change of heart, the current trajectory has Bosnia and Herzegovina heading right back to square one. We should all hope cooler heads and/or EU intervention will prevail. It is with great anticipation that we must rely on Brussels to rectify the mistakes they made in Bosnia and Herzegovina the first time and now in Ukraine. Should the country be allowed to descend into violence, we will have all failed our neighbours yet again.

So what now? More of the same.