INTERPOL: targeting international criminals, terrorists, and…activists?

On October 17, 2017, Russian officials put out a request for cooperation from the international community to locate and arrest William F. Browder by placing him on Interpol’s watch list. His crime? Maybe nothing more than lobbying.

Mr. Browder, CEO of Hermitage Capital Management, had worked in Russia for a decade when his vocal criticism of corruption and the challenges facing the Russian economy ran afoul of President Vladimir Putin, who had Mr. Browder’s visa revoked and had him deported. From his offices in London, Mr. Browder continued to criticize Putin and investigate police actions against his company with the help of his Moscow-based lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky. Mr. Magnitsky ended up spending almost a year in a Russian jail, where he died in November 2009. Reports after his death showed he died of “acute heart failure and toxic shock, caused by untreated pancreatitis,” but further investigations showed signs of severe beatings, and perhaps even torture.

Spurred by the questionable circumstances of his lawyer’s death, Mr. Browder has gone on to be a vocal activist and Putin critic, and led the US Congress to pass the Magnitsky Act, which sanctions the individuals involved in Mr. Magnitsky’s death, and now the passage of Canada’s very similar Bill S-226. One day before S-226, however, Mr. Browder popped up on an Interpol watch list through a diffusion notice and with a provisional ‘red notice.’

This has brought a long-standing controversy over Interpol’s notices and alerts system back into the public eye. Interpol, the International Criminal Police Organization, was founded to facilitate cooperation between police forces in different countries in order to overcome information barriers and target specifically transnational crimes such as trafficking, money laundering, and terrorism. The international notices and alerts system is a key facet of their information-sharing strategy. Eight different colour-coded notices can be sent out by the Secretariat, from a yellow notice about missing persons to the special light blue UNSC-Interpol notice.

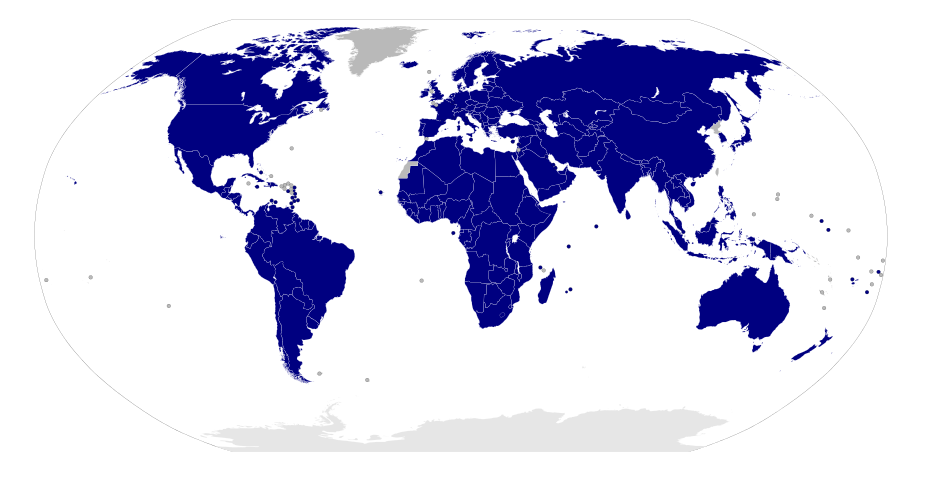

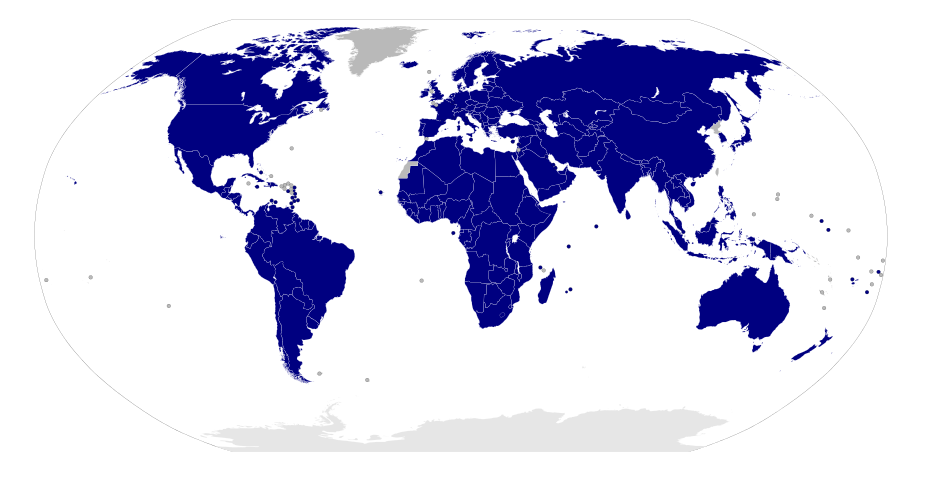

Interpol’s alert and diffusion systems have been criticized by governments and civil society organizations as a tool for countries to locate, harass, and force the extradition of individuals for purely political purposes. Critics point to the fact that every UN member state except North Korea is a member of Interpol with equal standing, which means that alerts by countries with strong rule of law are treated the same as alerts from known human rights violators.

The most notorious alert, of course, is the red notice. These notices request the location and arrest of wanted individuals so that they can be extradited and tried. Contrary to popular belief, red notices are not international arrest warrants – no member state is required to comply with any Interpol notice – but they are widely and effectively used to apprehend dangerous criminals around the world. Diffusions are also widely used as an informal request for the location or arrest of an individual, often while waiting for the approval of a red notice. The number of notices issued is on the rise due to the implementation of an electronic system, from fewer than 2000 being issued in 2011 to almost 20,000 in 2016, and the system is not without controversy.

This most recent alert was not the first time Mr. Browder has been targeted through Interpol’s institutions – it is the fifth. Notably, in 2013, Russia issued a red notice through Interpol after Mr. Browder’s conviction for tax fraud, in absentia; this notice was subsequently rescinded because of its political motive, and an attempt to file a red notice in August 2017 was denied.

Mr. Browder is not alone in being unfairly targeted. Kyle Parker, a policy director for the US Helsinki Commission, describes countries using it as “a way to extend their arm to harass opponents – political or economic.”

For instance, Michelle Betz, a US-Canadian journalist, had a red notice put out on her in 2011 by Egypt for “operating an NGO without a license.” She had been planning to train journalists in Cairo for the International Centre for Journalism and believes the request was made to intimidate her. Meanwhile, Azer Samadov fled Azerbaijan as a political refugee after receiving threats and harassment from the police force due to his involvement in opposition to the president. Despite his refugee status, he has been detained multiple times due to an Interpol red notice – issued by the very country he fled.

One of the most dangerous criminals targeted by Interpol? New Brunswick potato farmer Henk Tepper. He spent over a year in Lebanese jail after being apprehended based on an Interpol red notice while on a trade mission. Algeria had accused him of exporting rotten potatoes.

Interpol recognizes the potential for abuse of the notice and diffusion system and has review and complaint procedures in place to prevent these instances of illegitimate red notices. All red notices are subject to initial review by Interpol staff based on open source research and can be flagged for the legal section’s further investigation.

In the event an individual does not believe they should be on the watch list, they can make a complaint to the Commission for the Control of INTERPOL’s Files (CCF), an “independent, impartial body” that is in charge of requests for access and corrections. The CCF can review red notices and other notices in more detail and determines whether or not they are in keeping with Interpol’s constitution, which states that the organization is “strictly forbidden for the organization to undertake any intervention or activities of a political, military, religious or racial character.”

In addition, member countries are not obliged to act on a red notice. Countries such as Canada and the US do not automatically implement foreign arrest warrants. However, many countries still do – the US Interpol office estimates that a third of countries treat a red notice as a valid arrest warrant.

Even with the review system and complaint procedure through the CCF in place, states are still able to take advantage of Interpol’s notices system. Interpol mission is primarily to aid police cooperation, but without an independent investigative ability of its own and with a small budget, and it can be easy for things to slip by the initial review.

Filing a complaint with the CCF, meanwhile, can be time-consuming and extremely difficult. The CCF also has a relatively small capacity for complaints. In addition – and more concerningly – there is no way to appeal a CCF decision in any existing court, as it is not integrated into national or international court systems. Mr. Parker elaborates: “It’s not like fighting a criminal charge…[notices] can be more effective than the judicial system – with none of the safeguards.”

And even with initial and follow-up CCF reviews, the line between ‘legitimate’ motives and ‘political’ motives can be difficult to define. Consider the diffusion put out by Tunisia for ex-dictator Zine el Abidine Ben Ali and his wife after the Arab Spring in 2011. Could this be for legitimate criminal charges? Certainly, but it was also probably highly political in nature, with the new government going after the preceding regime.

The effects of being put on this watch list are not insignificant. Although red notices are not legally binding and do not result in an automatic extradition, the watch list is still highly regarded and will often result in detainment while traveling or visa denial. For instance, in Mr. Browder’s most recent case, his US visa was revoked not even 24 hours after the diffusion notice was put out and he was temporarily unable to fly to the States. Lutfullo Shamsutdinov, a human rights activist from Uzbekistan, was granted asylum in the US, but a red notice issued by Uzbekistan meant an extra five year wait for his green card approval. He was persecuted for reporting on a government massacre. In addition, most notices are posted publicly on Interpol’s website, which can be potentially ruinous for individuals’ reputations.

There are other ways states can misuse the Interpol alerts system. More ‘innocuous’ notices, such as blue notices requesting information on an individual, can also be used as a harassment technique by states. The Interpol’s other databases can also be abused. Two weeks after the attempted coup in Turkey, the government of Recep Erdogan canceled almost 75,000 passports, resulting in their entry in Interpol’s Stolen and Lost Travel Documents database. This database flags potentially invalid travel documents and could result in the denial of entry, boarding, or even the seizure of the document, potentially putting Turkish opposition members and activists in danger.

Almost a decade of criticism of Interpol’s alerts system has been able to push the organization towards reform. In 2014, a revised policy on refugees was adopted. Member nations are now encouraged to inform the central administration when individuals are granted refugee status, and all notices on refugees are flagged for review and generally not accepted if issued by the country they are fleeing. And in 2016, the CCF’s decisions on complaints became officially binding on Interpol’s administration and secretariat (before they were non-binding but generally followed) and the establishment of a clear timeline for the review process.

Nonetheless, these misleading and harassing notices and diffusions have continued. The Center for Peace Studies in Zagreb has published a number of suggested reforms. These include officially enshrining the right (if not the obligation) of a third party to trigger the review of a notice suspected of being politically-motivated and increasing the Secretariat and CCF’s institutional capacity to perform more timely and in-depth review of cases. But with rising numbers of red notice requests and shrinking budgets, this is unlikely to occur.

Overall, various organizations’ suggestions focus on transparency in the reporting and decision-making process. But Interpol’s actions are all made in order to maintain and promote police cooperation. This requires Interpol to maintain the buy-in of almost 200 independent police forces – and therefore not target or marginalize any state, minimizing its powers to enforce policies. Sanctioning nations that abuse the alerts system could risk driving them out of Interpol, creating criminal havens and reducing the effectiveness of the organization’s information sharing and cooperation. This might benefit people who are unfairly targeted by alerts but will also have broader implications on Interpol’s ability to catch some of the world’s most dangerous criminals and transnational crime networks that destroy lives every day.

For his part, Mr. Browder’s experiences with Interpol seem to be coming to a close. The US quickly reissued his visa, the diffusion notice has been canceled by Interpol, and Mr. Browder has reported that Interpol will no longer allow Russia to target him with notices. But he is just one person who has high-profile international allies and important resources. Without serious reform, Interpol’s watch lists risk becoming repressive regimes’ next most useful tool in tracking down and silencing dissent.

Julia Yingling is an Honours Political Science student at McGill University, studying Middle Eastern and international politics, security, and geography.

Edited by Pauline Werner