Is Algeria Doomed to Its Past?

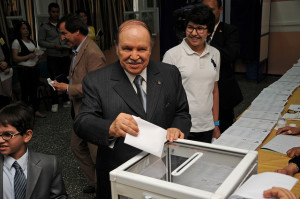

Just before the New Year, a group of Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s close associates demanded to meet with the former FLN revolutionary, as they had not seen him in over a year. Rumors swirled across the capital that a ruling clique headed by Mr. Bouteflika’s brother, Saïd, is making decisions behind the scenes in his name. Or that the military committed a ‘soft coup’ and is now pulling the strings in the country. While it remains unclear who exactly is in charge, the presidency announced and then received approval from the rubber-stamp Algerian Parliament for a set of constitutional amendments. These amendments include a two-term limit on the presidency, recognition of Amazigh (the language of the county’s Berber minority) as an official language, enlargement of parliament’s powers, and the creation of an independent electoral commission. Ironically Algeria had a two-term limit until Mr. Bouteflika abrogated that amendment by seeking a third bid in 2009 and a fourth in 2014, despite his notably poor health.

Mr. Bouteflika, clearly a man of another time, (and maybe with little time left), is an alarming symbol of the immobility of Algerian politics in the face of tremendous regional change. The country has been ruled by the same party, the National Liberation Front (FLN), since it gained independence from France in 1963. And while neighboring Tunisia and Libya threw off the chains of long-term dictatorships in the wave of popular protests in 2011 known as the Arab Spring, no serious protest movement emerged in Algeria. What explains the exception of this a regime? How is it able to maintain legitimacy when its current leader is quite possibly no more than a figurehead, a puppet?

Clearly the revolutionary fervor that spread so rapidly across the Middle East has now dissipated due to the horrific example of Syria, in which a non-violent protest movement has degenerated into a civil war that has claimed the lives of a quarter of a million Syrians and displaced millions more. But at the height of the Arab Spring in 2011, the Algerian regime shared many characteristics with the Ben Ali, Mubarak, and Gaddafi ones that should have made it just as vulnerable.

A potential explanation is that Algeria’s tremendous oil and natural gas reserves, which account for thirty-four percent of its GDP and sixty-five percent of the government’s revenue, allowed it to buy off protestors by providing greater subsidies and more government jobs. Indeed the government does provide tremendous subsidies to its citizens to the total of twenty percent of its GDP annually. Additionally following the outbreak of protests in neighboring Tunisia, the Algerian government “gave out free housing, low-interest loans, and huge bribes” to quell dissent. However this argument is undercut by the fact that Gaddafi’s Libya, which has the largest crude oil reserves in Africa, was unable to suppress the protest movement with a similar combination of side payments.

Another potential explanation is that the economic situation in Algeria was not as dire as in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. This is a plausible enough because the country notably contained inflation between 2000 and 2010, with the average rate amounting to 3.5%, whereas in Egypt inflation was especially rampant. Also Algeria’s international reserves amount to $200 billion, which gave it a considerable fiscal buffer even in this period of historically low oil prices. Notwithstanding these points of economic strength, the country’s unemployment figures suggest that there was ample motivation for protest. For example, Algeria’s youth unemployment has averaged over twenty-five percent since 2000. This is an important figure because it is reflects a similar level of youth unemployment widespread across the Middle East at the outbreak of the Arab Spring. The unemployed youth of Egypt and Tunisia proved essential to the success of the protest movements in each country because their social media savvy made it difficult for the authoritarian regime to suppress their protests and their lack of an established hierarchy made cooptation impossible. It is thus striking that Algeria’s disaffected youth failed to mobilize despite the negligence paid by the regime to their livelihoods.

However this is not to say that dissatisfaction with the regime is absent from the streets, rather it is contained and limited. Ten to twenty thousand small, local riots occur a year in Algeria, but not to beg for democracy. Instead these riots are a form of extracting material concessions from the government in the absence of other methods. In short, dissatisfaction with Algeria’s state-dominated, oil-export driven economy should have made the country ripe for mass protest and yet all that occurred was a series of minor, isolated protests. And while the economic concessions doled out by the regime may have bought it some time, it is unclear why the people remain so passive, despite the almost comical disappearance of their president.

The real key to understanding the current regime’s durability is the historical legacy of Algeria’s ‘Black Decade’. In the late 1980s the Algerian underwent a genuine liberalization of its political system. This allowed for the rise and then impending victory of the Islamic Salvation Party (FIS) in the 1992 parliamentary election, something the country’s military and civilian elite had not foreseen nor desired. This led to the military takeover that in turn prompted a nearly decade-long period of brutal conflict in which atrocities and torture was rampant on both sides. Bouteflika’s presidency was built on reconciliation and piecing the country back together. Although, it is now many years later, this conflict casts a long shadow that is evinced by the populace’s evident acquiescence to the political status quo. It remains to be seen whether the next generation of Algerians that did not live through the ‘black decade’ will also succumb to political apathy despite the apparent remove and ineptitude of the country’s ruling clique.