Is Colombian Peace under Threat?

Photo provided by the author.

Photo provided by the author.

In 2016, Colombia made headlines when President Juan Manuel Santos accepted the historic Peace Agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)—one of the most notorious leftist guerrilla groups. This historic deal brought an official end to Colombia’s 60-year civil war and placed the burden of peace on the Colombian state, which now includes FARC as an official party.

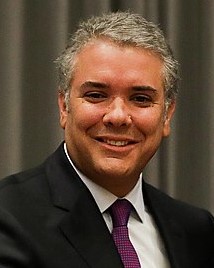

At the beginning of March 2019, Colombia’s peace agreement made headlines again when President Iván Duque Márquez announced a plan to reform the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP)—a non-partisan, transitional court established to try all participants of the conflict independent of their affiliation. Duque issued a presidential veto that targets 6 out of the 159 articles of the statutory law governing these panels. This action is notable because it not only attempts to alter a law that has already been approved by the Constitutional Court, but also because it specifically targets FARC and other ‘non-governmental’ groups while subtly reducing the risk of prosecution for ‘state’ actors.

A Dangerous Game

Despite the seemingly small number of changes his veto calls for, the simple act of overriding this law—which is seen as the backbone of the Peace Agreement internationally—has ignited tensions between the executive and judicial branches of the Colombian government. In 2016, following the Havana Negotiations, the Constitutional Court approved all 159 articles. Allowing this veto would set a dangerous precedent of undermining the judicial branch while further emboldening the executive branch. Many Colombians fear that this veto will not only jeopardize the already-slow process but also see it as an overreach of executive power that questions the very rule of law.

Executive power is already a complex issue in Colombia, and Latin America more generally, due to a long history of this branch overstepping its limits and consolidating power that belongs to other branches. The recent situation in Venezuela is a prime example of this phenomena, in which Maduro has rejected the National Assembly’s constitutional intervention and assumption of executive power. This overreach in relation to the Colombian Peace Process is even more controversial since the executive branch accepted the peace agreement back in 2016, despite it losing by a slim margin of 49.8 percent yes to 50.2 percent no in a national referendum.

If the veto proceeds, all 159 articles will lose their status as statutory, which is what gives these panels their authority. While Duque justified this veto as a means of fulfilling a campaign promise to impose harsher punishments on FARC and other guerrilla leaders, many Colombians—despite sympathizing with this sentiment—feel that the very act of vetoing jeopardizes the integrity of the deal and the legitimacy of the state’s function. This veto would slow the process of justice and “undermine the same accountability it [the state] has the stated purpose of promoting” according to UN human rights chief in Colombia, Alberto Brunori.

Peace and Politics

Aside from institutional tensions, Duque’s veto questions the role of the state and its ability to serve as a neutral party in implementing the Peace Agreement. As a conservative and the leader of a centre-right government, many perceive this veto as an attack against the ‘left-wing’ JEP panels. Despite his stated purpose of reforming the tribunals, his partisan-driven motives question the state’s ability to act as a neutral leader. The approval of the veto will set a dangerous precedent allowing each new regime to propose changes to the Peace Agreement, which is meant to act as a long-term transition plan that transcends party politics and specific regimes. For the agreement to be considered valid, there need to be certain safeguards that prevent individual regimes from making changes based on partisan agendas. If changes are to be made, the parties must follow detailed and previously agreed upon processes that are open to all actors—not just the ‘state.’

A State for All

This, however, raises another important issue: the input of Colombians who should have a say in the process. Thus far, they have been alienated by the state as it has consistently overridden their democratic response. There is no doubt that the presence of political and personal views complicates the peace process, but when dealing with such an influential actor—who is also a participant in the conflict—the complexity of the situation is magnified.

In Colombia, the state is a function of the people and thus should be able to make changes that reflect the dynamic desires of the people. More broadly, this conflict can be traced back to a negligent state who ignored the plight of its rural and lower-class citizens in the first place. While this reality makes the state’s role in the peace process controversial, the state is the only logical actor that can guarantee an enduring peace, but it is simultaneously the backbone of order in the country and the root of its conflict. An enduring resolution thus depends on rebuilding the relationship between the state and the people it represents.

The state must serve as a function of all people, including FARC and other guerrilla groups, as they are Colombian too. To further isolate them would only perpetuate tensions and likely lead to a return to violence. In this sense, the state must take on a moderate role that Duque’s antagonist veto contradicts.

This veto would undo the fragile yet fair solutions that address the ambiguous role of the state. One of his reforms would eliminate a provision preventing cases involving members of the state’s armed forces to be tried in the state’s regular courts. This change would favor ‘state’ actors while disproportionately targeting FARC and other guerrilla groups. all of which would likely reduce the prosecution of state actors. Another reform would eliminate a practical provision instructing the tribunals to focus on those ‘most’ responsible, such as those in command.

This practical provision though has actually already been met with criticism from those in favour of the tribunals, specifically the victims. Currently, the systematic approach in identifying and prosecuting those in positions of authority means that they do not necessarily try individual cases. Social activist Yolanda Perea Mosquera understands and even agrees with the logic and utility of this approach, but as a survivor of sexual assault herself—being only 11 when it occurred—she also highlights the need for individuals to share their stories.

Recognition for Reconciliation

Beyond a restoration of order, an enduring peace requires the recognition and reintegration of individual victims who have been abandoned and prosecuted by all sides involved. They, more so than others, feel an overwhelming sense of isolation from both the state and Colombians more generally, which the systematic approach of the tribunals only reinforces.

In terms of healing and reconciliation, their stories must not only be recognized but incorporated into the narrative of this conflict so as not to fall outside of a history that they should define. There is both a collective and individual process of healing. Victims must not only be heard but also validated, which is difficult when dealing with a conflict as large and long-term conflict as Colombia’s.

More generally, Colombians need a sense of closure, which will only come from restoring a sense of justice that these tribunals have begun to address.

What Now?

The veto is contingent on its approval by both houses in parliament, but Duque’s government does not have control of either house. However, neither does his opposition. The veto has led to heated debate in parliament and was ultimately rejected, but the damage had already been done. The entire ordeal has called into question the validity of the peace proceedings in Colombia, specifically highlighting the controversial role of the state and thus threatening its ability to rebuild trust with all Colombians.