Italy’s Crisis: Weak Government and Political Fragmentation in the Second Republic

Italian politics is anything but stable. What's going on?

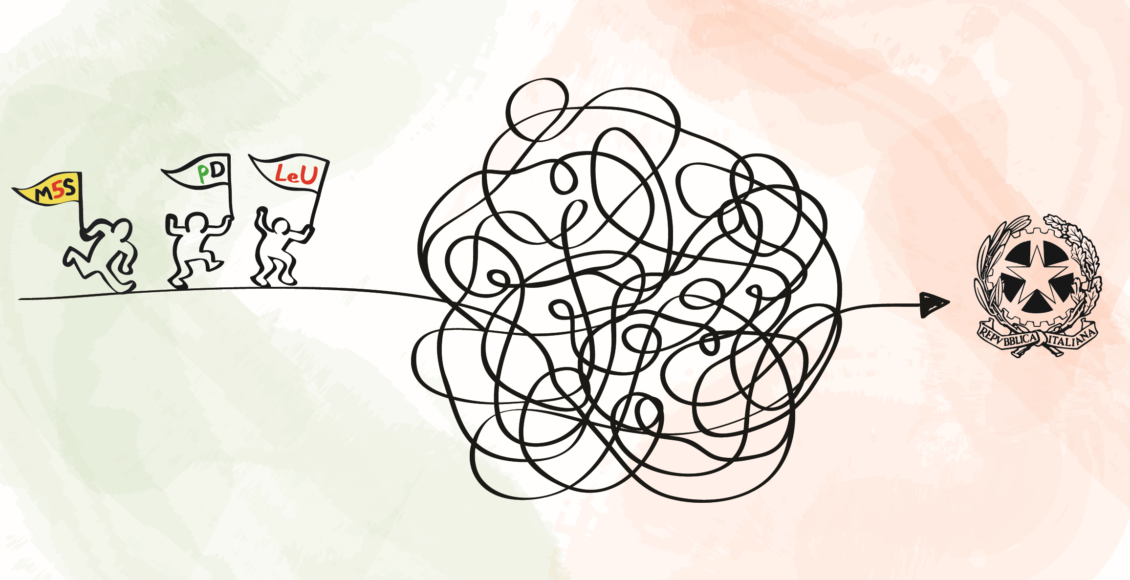

Third time’s the charm—or perhaps, should we say the seventh? For the seventh time in the last ten years, September 5th saw Italy form a new government, led by the big-tent Five Star Movement (Ms5), the country’s current largest party. Joining the MS5 in coalition is the centre-left Democratic Party (PD), a one-time political main staple that has now shrunk to a measly third place. With the former virulently anti-establishment and the latter as establishment as they come, this shaky alliance has come to be known as the “giallo-rosso,” based on the respective colours of the parties involved. Superintending the monumental task of leading a government composed of diametrically opposed parties is Giuseppe Conte, the Prime Minister. Conte, a political independent, first rose to become head of government in 2018 under the Ms5-Lega Nord (LN) alliance, which lasted just over a year before collapsing amid political infighting. However, the second Conte government may prove even feebler than the first, as ex-PD Prime Minister Matteo Renzi (2014-16) split his former party just weeks after the giallo-rosso was formed, establishing a new centrist party that siphoned 26 seats off the government.

With this in mind, it is extremely doubtful that this already troubled coalition will survive a full year, let alone persist until the mandatory general election of 2023, but this is far from unusual in Italian politics. Short-lived coalition governments characterized by volatility are commonplace. Since the end of World War II, the nation has undergone 66 different governments, with the average lasting just over 13 months. How has Italy, the birthplace of Renaissance values including civil society and citizen engagement, become the sick man of Europe, politically speaking?

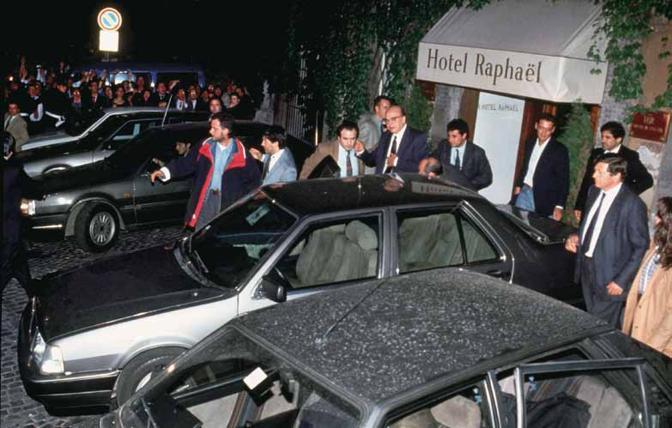

In order to ascertain the illness plaguing the Italian political system, we must jump back to the end of the 20th century. From 1946 until 1994, Italy was a dominant-party state. The Christian Democrats (DC) won every single election, aided by its clientelistic relationship with the Catholic Church, major Italian industries (such as FIAT Automobiles, one of the DC’s major donors), and other benefactors who sought to keep out the number-two Italian Communist Party at any cost. Although governments and the cabinet leaders who led them were frequently reorganized, the DC was never dislodged from power for almost 50 years. And in an instant, it all came crashing down. In the early 1990s, the Tangentopoli scandal saw the Italian courts expose decades of corruption between DC politicians and their benefactors through widely publicized trials over TV and newspapers that scandalized the disgusted voter body. Endless resignations followed in addition to some arrests, and there was even the occasional suicide. With the nation in total political disarray, a referendum was called in 1993 to reorganize the structure of government, laying the political framework for the Italian “Second Republic” of the 21st century. Hell is full of good intentions, for it was the fear of further corruption arising from long-term dominant-party rule that led Italians to refashion their entire political system—creating the problems of today.

Although the major parties in Italy advocated for the status quo to be maintained, with ex-Prime Minister Bettino Craxi even famously advising the electorate to ‘go to the seaside’ and enjoy themselves rather than vote for change, a massive 62.5% of Italians turned out for the referendum. All eight major political reforms to the constitution were accepted by the Italian people. Most importantly, the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house) and the Senate (the upper house) received new electoral systems. In the Chamber, existing seats elected by proportional representation (PR) were joined by several new seats elected by the “first-past-the-post” method, absent in the previous system. In the Senate, PR was abolished entirely. This new system of single-seat constituencies elected by plurality was designed to foster a two-party political system, in order to bar a dominant party from latching onto power for too long, thus preventing the corruption of the First Republic from occurring anew. Similarly, the abolishing of PR in the Senate was designed to elevate the upper house to coequal status with the Chamber of Deputies.

Instead, Italy dashed too far in the opposite direction: power was made more brittle than ever before. Since the referendum, only one government has served a full five-year term. The Porcellum voting law has only made matters even worse. Beginning in 2005, the party that receives the most votes in the Chamber receives a “majority prize” (extra seats), therefore allowing for unusually powerful majorities to form in the lower house. This is the key issue. The 1993 electoral changes in the Senate were designed to make the upper house an equal decision-making body with the Chamber, yet voting laws such as the Porcellum contrastingly allow majorities to be stronger in the Chamber than in the Senate. Unavoidable political gridlock has thus defined the relationship between the two houses of legislature. Despite this, the electorate has proved unwilling to reject equal bicameralism, perhaps in fear of reviving the pervasive corruption of the First Republic. In 2016, PM Renzi’s constitutional referendum, which included a provision abolishing the equal role of Senate and Chamber, was rejected by the people 41-59% and subsequently prompted his own government’s collapse.

This turmoil in the Italian political system can also be analyzed from a different lens. Since the ignoble beginnings of the Second Republic amid corruption and crime, a “culture of crisis” has permeated Italian society. The Tangentopoli crisis, repeatedly rammed down the throats of the average Italian by newspaper and television alike as the “crime of the century,” awoke a sense of apathy in Italians for the government that has never really subsided. The fact remains that the millennial generation and onward experience higher unemployment levels, weaker job security (particularly post-2008), and fewer opportunities to securely start a family, with the Italian birth rate being among the lowest in all Europe. La Crisi should therefore be understood in two parts: half a disgust for politicians and the political sphere itself, and half a fear in young people that they will never be able to live a good life. Populist strongmen like Silvio Berlusconi (three-time Prime Minister) have emerged because of La Crisi, promising to be different than the “average politician” and to care for the overlooked concerns of the disgruntled ordinary Italian. However, his own long and controversial legacy has done nothing but leave Italians even more politically divided than ever before.

There seems to be little hope of a resolution on the horizon for this two-front Italian crisis. The ineptitude of Italy’s political system persists to this day, as does La Crisi among her people. Where will these intertwined issues take the country in the future? In his book The Archipelago: Italy Since 1945, British academic John Foot comments on the current turmoil of the Italian political system, stating that “the failure of the state [may come to be blamed] on the opposition…or on ethnic and racial minorities. If progressive forces fail to impose their own solution, the country will seek salvation in a “divine leader.” Writing in 2017, Foot was unsure if this ‘Caesar’ had yet to appear on the scene. Two years later, I will attempt to furnish two best guesses.

Firstly, this ‘Caesar’ might be the MS5 party as a whole, currently in government. Their emergence in 2018 fits well with Foot’s prediction of state failure being cast at the feet of the nameless “opposition,” as the Five Star Movement is highly anti-globalization, populist, and critical of the forces of the establishment, including both traditional Italian parties and the European Union. Alternatively, this new ‘Caesar’ may be Matteo Salvini, head of the LN. Although he briefly formed a coalition government with the MS5 from 2018-19, Salvini was subsequently sidelined. However, his political career is anything but finished. As of October, Salvini’s LN, a right-wing populist party which has blamed much of Italy’s problems on migrants from the Middle East and Africa, is the most popular party going into the next election, having grown at the expense of the MS5. Perhaps most fitting with Italy’s own classical history, we should utilize Foot’s prediction to evaluate them both as twin ‘Caesars.’ If we equate the MS5 with Ancient Rome’s very own Julius Caesar, a populist forerunner laying the groundwork just short of total political upheaval against a widely unpopular establishment, we should hence envision Salvini and the LN as the parallel of Caesar Augustus, the successor to an ill-fated predecessor who will (likely, in Salvini’s case) actualize tremendous political change going into the future.

Featured image created by Ella Roy.

Edited by Brian McGinn