Japan’s Uncomfortable Past

A sta

A sta

On October 4th, the city of Osaka in Japan cut ties with its sister-city, San Francisco due to the controversy surrounding a statue depicting three comfort women from China, Korea, and the Philippines. The statue is called “Women’s Column of Strength”, and was erected to memorialize the women and girls who were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army before and during the Second World War.

The controversy surrounding comfort women is not a recent phenomenon – it is believed to date back to the early 20th when the Japanese embarked on conquests in the Pacific. The Japanese, however, vehemently deny this fact and their refusal to accept any kind of blame or responsibility has long-since plagued Japan’s postwar relations with its Asian neighbours, especially with US-Aligned South Korea. The continued strain between Japan and South Korea over the issue of comfort women is problematic considering that Japan and South Korea act as a united Western-oriented bulwark against China’s growing clout in East Asia and without this unified front, China could develop an unparalleled presence over the entire region.

The undermining of Japanese-South Korean relations occurred most recently in September 2018, as South Korean President Moon-Jae-In hinted at the dissolution of an agreement made in 2015, which was intended to be “final and irreversible”. This 2015 agreement was made between Japanese Prime Minister Abe and the conservative South Korean President Park Geun-Hye to settle their interstate historical disputes surrounding comfort women. The agreement was formulated in the context of mutual concerns over China’s growing power in East Asia as well as a growing fear of North Korea’s nuclear ambitions.

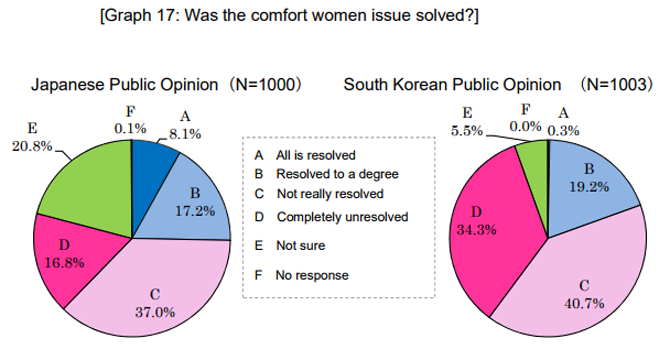

As part of the agreement, the Japanese government apologized for its actions, and contributed $8.9 million dollars to the Reconciliation and Healing Foundation to support its victims, the foundation’s purpose is to distribute funds from the Japanese and South Korean governments to surviving comfort women. In return, South Korea promised to no longer raise the issue of comfort women at international forums, as well as discuss Japan’s grievances at the erection of a statue memorializing comfort women by Korean civil society in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul. However, this agreement was challenged from the onset, as South Korean critics contended that the agreement sold out the dignity of the survivors in return for geopolitical gain. Public opposition to the agreement steadily grew in South Korea, with the erection of yet another statue in 2017 in the port city of Pusan by South Korean artists that was also thought to memorialize comfort women. Although the statue was initially removed by the police, it was reinstated after several weeks later due to tremendous public pressure.

The statue’s reinstatement prompted the withdrawal of Japanese diplomats from South Korea and prompted a three-month diplomatic standoff between Japan and South Korea. Seoul argued that they had fulfilled their end of the bargain by discussing the removal of the statue, but Japan responded by claiming that mere discussions were not enough and that in order to fulfill the agreement the statue needed to be removed. The Japanese diplomats were eventually permitted to return a month before the inauguration of South Korean president Moon Jae-In, and his liberal administration is unlikely to cave to Japanese diplomatic pressure regarding the removal of the comfort women statues.

President Moon’s attitude regarding comfort women was unique from the onset as he became the first South Korean President to use the term “comfort women” in his United Nations speech in 2018. President Moon’s choice to use the controversial term stems from both his opposition to the 2015 agreement as well as his personal convictions regarding the subject, as he has repeatedly called on the Japanese government to “act on the basis of remorse and reconciliation” in order to manage Korean-Japanese relations and, in doing so, acknowledge the historical truth. Thus, President Moon is unlikely to view the Japanese withdrawal of diplomats in 2017 in response to a statue depitcing comfort women as a fair demonstration of Japan’s remorse for the past.

The validity of Japan’s remorse is further questioned when examining the current Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe’s, views on the subject of comfort women. As Prime Minister, Abe is part of the LDP committee for historical investigation – a group which publicly opposes the claim that comfort women were used by the Japanese military during the Second World War. In addition, Prime Minister Abe previously forced the NHK (Japan’s National Broadcasting Company) to omit sections of a documentary about the Second World War which included references to comfort women.

A brief summary of the current controversy surrounding comfort women only scratches the surface of the issue and leaves a critical question unanswered: what can be done about the issue? The United States must take a firmer stance in East Asia, which can be done by seizing a leadership position in the region through the formation of a long overdue Asia-Policy by the Trump administration. This will permit US allies in the region, especially South Korea and Japan, to rally around a unified cause. Additionally, in the past, Washington has been highly vocal in denouncing Prime Minister Abe’s attempts to renounce the Kono Statement, an official recognition by the Japanese government of comfort women. Therefore, going forward, Washington must not only solidify their position in the debate, but also take active efforts to reconcile the differences between South Korea and Japan. Only through reconciliation of the issue can the differences between South Korea and Japan be resolved and only through such a resolution can South Korea and Japan successfully provide a unified front against growing Chinese influence in the region.