Labour’s Love Lost: The Party’s Unsure Path Post-Corbyn

This royal throne of kings, this scepter'd isle, this earth of majesty, this seat of Mars—can Labour reclaim it?

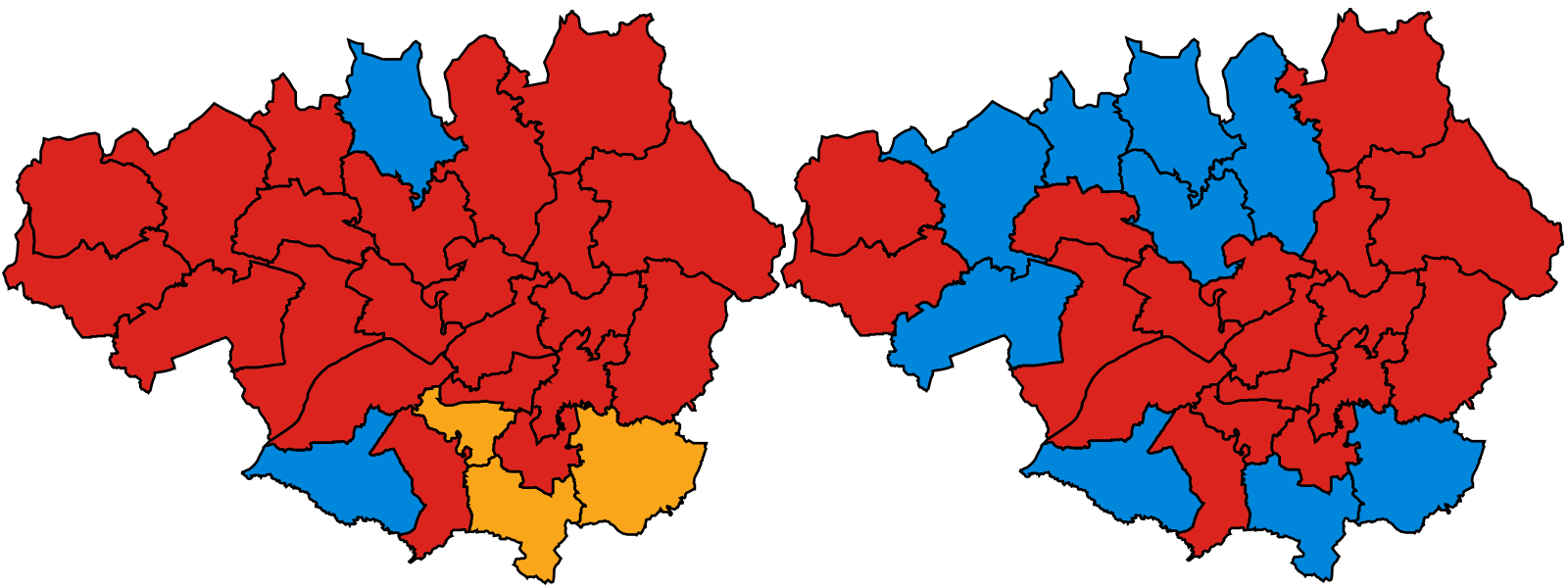

Let’s not mince words—the Labour Party of the United Kingdom lies in tatters. The Conservatives claimed 365 seats and won a landslide victory last December, forming their largest majority in Parliament since 1987. In the process, Labour lost 60 seats as the party’s support crumbled in their once-loyal mainstays of Wales, the Midlands, and the North East. Most notably, former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s previous riding of Sedgefield flipped to the Tories for the first time since 1931; as did Bolsover in Derbyshire, which brought an end to the four-decade long career of the acerbic Labour MP Dennis Skinner.

Some have attributed the Conservative victory to Brexit, as a significant amount of voters on the left flirted with Euroscepticism, disagreeing with the European Union’s open labour market and free movement laws. It has been estimated that up to 800,000 Labour supporters voted “Leave” during Brexit. Others have placed blame for the fall of the “red wall”, Labour’s heartlands in north-to-central England, at the feet of Jeremy Corbyn. With 76% of the electorate espousing a negative opinion of the Labour leader in the months prior to the election, Mr. Corbyn, who pulled the party sharply to the left from his Blairite predecessors, remains the most unpopular Head of the Opposition of the last 45 years. However, if a figure like David Cameron was successfully able to lead the Tories to renewed victory 13 years after their dramatic defeat in 1997, a new Labour leader can certainly help the party to recover from this loss going into the future. The question remains: what steps must this leader take to do so?

Listen to their Voters’ Concerns on Immigration

Cottonopolis, Warehouse City—industrial Manchester is Labour, or at least, it was. Despite its prominent status as the cradle of the working class and British radical politics, Labour has recently begun to ebb within its boundaries. Four MPs in the Greater Manchester Area flipped from red to blue in last year’s election, but the Conservatives have been making gradual inroads as early as 2010. A pressing issue for local voters is immigration. In 2001, Oldham (a city within Manchester) violently erupted into race riots between native Britons and the South Asian immigrant population. Twenty years later, these ethnic tensions are not as conspicuous but persist nonetheless.

The British Independent Office for Police Conduct recently published a report into the failings of police and social workers in the city, concluding that vulnerable girls as young as twelve had been groomed and abused in “plain sight.” Although the police were aware that a pedophile network of Pakistani men preyed upon young British girls, accusations of sexual abuse were not only ignored—but were deliberately suppressed by police—in order to prevent Manchester from plunging into sectarian violence anew. In 2017, the city also became the site of a horrific Islamic terrorist attack at a concert that killed 23 (many of whom were teenagers) and wounded more than 800, the deadliest attack in all Britain since the 2005 London bombings. In light of these troubling events, the issues of unregulated immigration and cultural assimilation loom large in the minds of Manchester’s residents.

The problem at hand is simple: many British Labour voters want greater controls on immigration, but left-wing activists, a “sizeable constituency…for whom border controls are racist by definition,” oppose the silent majority. In contrast, the Tories will likely continue to promote a stringent stance on immigration and related social issues that have won over many Labour voters in increasingly multicultural areas like Manchester. Former Chancellor of the Exchequer Sajid Javid, a high-ranking Tory of Pakistani heritage, has gone on record stating it was “wrong to ignore” the ethnicity of grooming gangs, arguing that disregarding the electorate’s concerns about immigration and assimilation could deliver voters into the arms of extremist far-right fringe groups.

Despite the reservations held by large sections of their base, the Labour party higher-ups have remained strikingly tone-deaf, appealing to activists over voters. Although Corbyn promised to “compromise on immigration,” delegates at Labour’s annual conference unanimously backed a motion committing the party to “free movement, equality, and rights for migrants.” Many former Labour voters, seeing Corbyn as disingenuous on immigration issues due to the radical stance taken by his party, voted accordingly in 2019. The current left-ward shift within Labour over immigration is a recent phenomenon. In the past, former Labour leader Ed Miliband promised to take the matter seriously, stating: “…it isn’t prejudiced to worry about immigration, it is understandable.” To regain lost ground, Labour must digress from its unpopular stance on the matter and actually heed the concerns of their voters. A change in attitude will do well to recapture long-alienated voters within Labour’s traditional constituencies.

Embracing the Blue Labour Movement

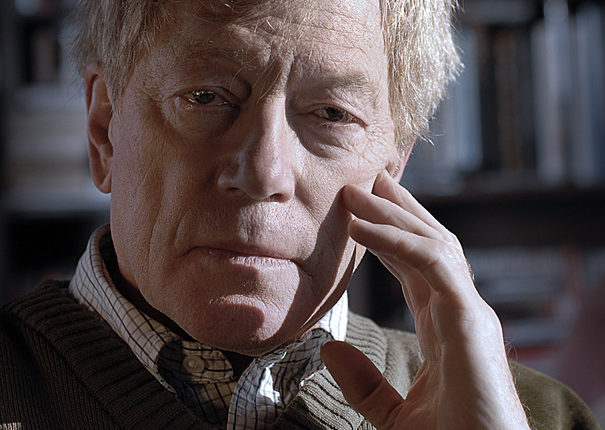

The internal divide within Labour over issues like immigration and Brexit lays bare a greater phenomenon permeating the British left. Many voters maintain strong conservative values at heart, while simultaneously rejecting the neoliberal free-market model advocated by the Tories and middle-way Blairites. Enter Blue Labour, an advocacy group associated with the Labour party and founded by the peer Maurice Glasman, which advocates “a socialism which is economically radical [but] culturally conservative.” The organization looks back in time to the nascent Labour movement of the early 20th century for answers to modern-day issues. In contrast to Labour’s post-1945 managerial style of government, disseminating services through a top-down bureaucracy, figures like the Lord Glasman prescribe a more communitarian approach to the welfare state. Instead of state-driven distributive policy, Glasman contends that Labour should return to a “relational” style of politics, where the state delegates wealth and power back to local communities. Through this arrangement, Labour would deviate from the Eurocommunist model out of which Corbynism emerged and revive the practices of Old Labour: mutuals, co-operatives, friendly societies, local banks, and workers’ representation on companies. Just as the original Labour Party was staffed by Methodist activists preaching the importance of establishing a government serving the needs of individual communities, Blue Labour seeks a return to form: to implement a kind of secular Methodism for 21st century Britain. While Blue Labour is “culturally conservative,” supporting a unified Britain and taking a strong stance against crime, immigration and the European Union, it is still supportive of LGBT rights and takes a hard stance against racism. Academic and Blue Labour advocate Jonathan Rutherford, while discussing recently deceased British philosopher Roger Scruton, best describes Blue Labour’s political philosophy:

“The left has followed the liberal philosopher Friedrich Hayek’s disparaging view of conservatism in his essay, “Why I Am Not A Conservative.” Conservatism, writes Hayek, with its fear of change and timid distrust of the new, is dragged along paths not of its choosing, constantly applying the “brake on the vehicle of progress”. But we have all learned that things don’t only get better. The destructive impact of liberal economics over the last 40 years requires that we recognise the enduring presence and value of the conservative instinct in society. As [Roger] Scruton argues, the market has a corrosive effect on human settlement.”

Having rejected the emphasis on free-market capitalism implemented from Margaret Thatcher onwards, Rutherford utilizes the conservative Scruton’s love of tradition and community to express Blue Labour’s own stance.

“Scruton’s conservatism is a philosophy of attachment. He describes it as a love of home, by which he means the common life and inheritance that belongs to “us”, the people, and which grows out of everyday life. This “us” is not made by contract and nor is it ethnic in its origins. It is membership which is made in the ordinary life of friendship, family, community and love of place.”

[Scruton’s views], on the state of Britain, should be widely read on the left.

In sum, Blue Labour cannot be thought of as “blue” for being socially conservative, but rather for being conservative socialism: a mode of government that seeks to elevate family and the community at the “heart of a new politics of reciprocity, mutuality, and solidarity.” When internationalist obligations such as those imposed by the European Union threaten the stability of British families and communities, Blue Labour affirms they must be rejected in favour of the good of the nation. The latent potential of Blue Labour is significant for the following reasons. First, when a political party is publicly perceived as patriotic—but also supplemented by a strong social welfare framework— they can achieve mass appeal, and thus a greater chance of winning. Second, there has already been substantial support for Blue Labour-esque policies in past years. The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), a Eurosceptic populist party, which became the largest British party in the European Parliament in the mid-2010s, similarly adhered to a conservative political agenda affirming national identity, while simultaneously eschewing European integration and the negative outcomes of 21st-century neoliberalism. Consequently, one of their largest support bases became the working-class, largely situated in Labour-voting districts. With the British electorate having responded well to this economically-left and socially-right mélange before, it is plausible that Blue Labour thought may soon acquire more traction should the party seek to reconnect with voters previously disaffected with Corbyn.

Blue Labour — A Loving “Longshanks” to Quash Scottish Independence?

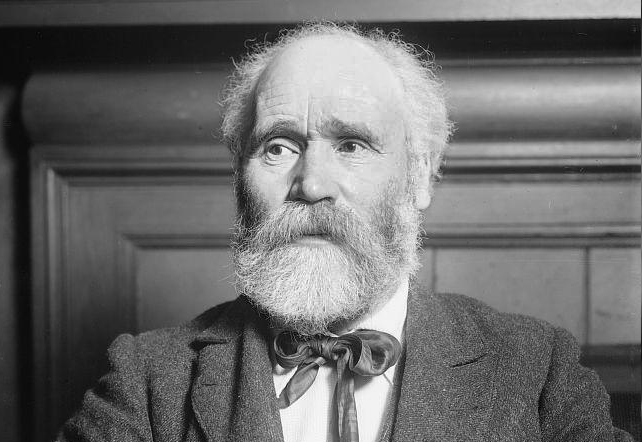

Lastly, a revitalized party operating under the auspices of “Blue Labour” could aid in drawing the increasingly outward-looking Scots back into the British fold—and in turn, allow Labour to recover from the brink of collapse. Last December, Labour was reduced to just one seat in Scotland, its lowest share of the vote since 1910. Despite this precarious position, the combined Conservatives, Liberal Democrats and Labour (all anti-independence) still collectively control 55% of the vote, compared to the Scottish National Party (SNP) with 45%. However, it was not so long ago in 2010 where Labour was in the opposite position, with 42% of the Scottish vote and 41 out of 59 seats under their belt. As the internal political divide in Scotland worsens, something must be done to warm relations between Edinburgh and London. The Lord Glasman, architect of Blue Labour, affirms how his movement can do so by reining in the creeping Scottish National Party and granting Labour newfound political relevance there. The statist model currently preached by Labour has not fared well in an area increasingly supportive of political devolution. With this in mind, Blue Labour’s wish to make the community the locus of governance rather than the state bureaucracy may find fertile ground in headstrong Scotland. The Lord Glasman also believes the Labour Party must look back to its Scottish founder, Keir Hardie, for guidance in the present. Congregationalism, steeped in the ideas of Scottish Presbyterianism, formed a key part of Hardie’s early Labour platform, wherein each church congregation would be able to run their own affairs autonomously. By re-asserting traditional Scottish methods of religious governance within the context of the modern secular state, Blue Labour intends to implement “Scottish-derived,” bottom-up, community-centred methods of governance. This may ultimately turn the Scots away from the monolithic SNP in favour of Labour. Furthermore, as Glasman notes, Scotland’s left-leaning working class shares with its English counterpart a disposition of cultural conservatism which is amenable to the ideals of Blue Labour’s conservative socialism.

Where Blue Labour Fits Into the Upcoming Leadership Election

Among the current contenders for the Labour leadership, only Lisa Nandy holds true to the “Blue Labour” vision that emerged out of the Miliband era. Nandy, much like Glasman, has stressed the importance of community and co-operation in accordance with the “old traditions of ethical socialism.” Similarly, she has asserted that patriotism must not become “the exclusive property of the right in British politics.” Although Nandy remains in third-place behind candidates like Sir Keir Starmer, a softer leftist than Corbyn, and Rebecca Long-Bailey, a dyed-in-the-wool Corbynista—don’t discount Blue Labour just yet. If no candidate receives a majority in the first round of voting (as is likely to be the case), preliminary results from January show Nandy’s support will be largely redirected to Starmer, rather than to Long-Bailey. If Blue Labour’s support causes the scales to tip in Starmer’s favour, he will need to make serious concessions to the movement to maintain their support once in power.

Featured Image: State Opening December 2019 by UK Parliament is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Anthony Kuan