Laïcité in France: From Freedom of the Church to the Protection of a Judeo-Christian Exceptionalism

From MIR's featured series on religion and human rights.

In July 2021, the French Parliament adopted a law entitled “Law Reinforcing the Respect of the Principles of the Republic”. The law is notably meant to tighten control of the foreign financing of associations, including religious ones. Proposing an amendment to this law, two deputies of the governing party La République En Marche (LREM) sought to prohibit the wearing of the veil for young girls. While rejected by the commission, this proposal suggests that the concept of laïcité raises multiple questions in France. At the heart of this debate: freedom of religion.

Laïcité is a core value in France. It may not be a part of the “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” triptych but it resonates with each of these values just the same. Yet, this concept has not always been a term justifying exclusion as it is today but has devolved from the tolerant and egalitarian concept of its revolutionary roots. In shedding light on the confusing term that is laïcité, France needs to come back to the original conception of laïcité – coined in the 1905 law – that was meant to create a break between the Church and a neutral state. Only this understanding reflects the French values of “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité”. This move towards a more neutral, yet tolerant position of the state would safeguard religious diversity while reversing the dominance of the tradition in France that has been used to justify stances and policies favoring Catholicism over other religions.

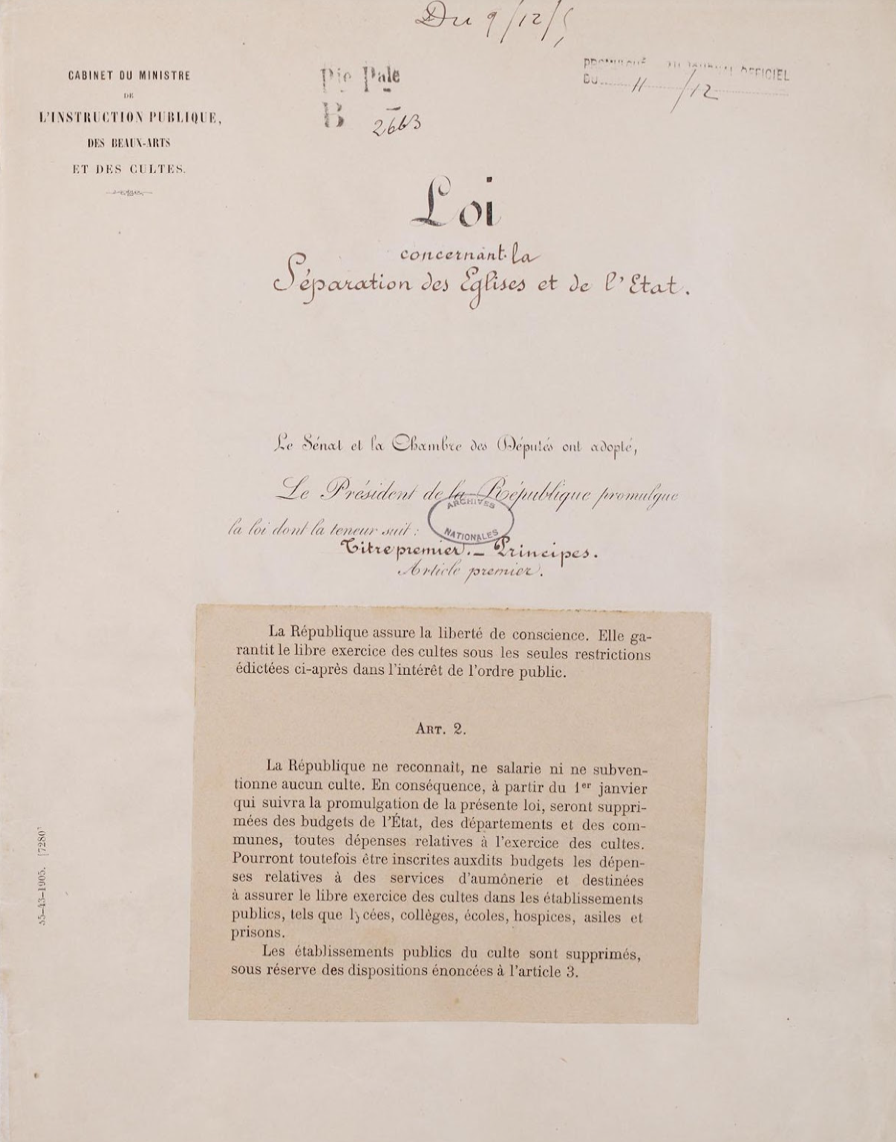

Laïcité is a concept that emerged in the wake of the French Revolution to establish a secular French Republic. Following the Revolution of 1789, anti-clerical revolutionaries crafted a regime that would give full authority to an elected political body, therefore sidelining any opposing forces, such as the Church. This vision of France weakened the Catholic Church’s role in the public sphere and allowed religious pluralism to flourish. Under the Third Republic, the separation between the Church and the State was officially entrenched in law with the 1905 law, placing France on a secularizing path [1].

However, since the 1980s, events such as the 1979 Iranian Revolution have triggered a new interest in debating the role of the state in religious affairs – particularly putting Islam under the microscope. In France, the debate around religion, especially Islam, materialized in the 1989 case about young girls wishing to wear the Islamic veil to attend school in Creil [2]. The 1989 statement of the court has only fed intense debates. The Conseil d’Etat ruled that a headteacher had the right to establish some limits on the expression of religious faith for students. Far from being a consensual value around which the French people gather, laïcité has become a divisive concept.

The different understandings and applications of laïcité throughout its history can be explained by a conflict in values. The framers of the 1905 law, such as the socialist Aristide Briand, understood laïcité as a principle enabling vivre-ensemble between believers and non-believers. This tolerant view allows believers of different faiths to cohabit within a republican common setting. In practice, the state does intervene in religious matters and the numerous exceptions to the separation principle lead to the conclusion that this separation between Church and State was never intended to be strictly respected [3]. Building on this ambiguity, laïcité is today invoked to legislate upon religious practices impacting the public space. As such, a more restrictive definition of laïcité guides French politics. The law of 2004 illustrates this well; the prohibition of wearing religious signs is a restriction of freedom.

This duality within the laïcité concept leaves us to ponder: Do we need to embrace further the shift initiated by the 2004 law or do we need to remain loyal to the spirit of the 1905 law? The answer becomes more clear when we draw on the foundational values of France, which do not align with the more restrictive definition of laïcité, that both revolutionaries and the framers of the 1905 law advocated for as a guide. The capacity of laïcité to reduce potential conflicts no longer holds since the same concept today is used to inflame tensions. Yet, since laïcité is at the core of the French identity, the lack of consensus around the concept polarizes political debates and allows non-tolerant political actors to make their way to power.

The 2004 law, despite its apparent neutrality, disproportionately affects Muslim religious groups compared to Catholics. Indeed, Catholics are not expected to wear an ostentatious sign -except maybe a cross- to express their faith. While Muslim minorities and especially Muslim women are restricted in their rights to wear the veil as a sign of their faith, Catholicism is still granted some exceptions that are justified in the name of a Judeo-Christian tradition of the French nation. Seeing a nun with her religious clothes is not perceived as offending contrarily to a woman wearing a veil. This common perception highlights the difference in treatment that is observed between religious groups. Involving even more direct state involvement, the French State of Alsace-Moselle recognizes only four religions – three Christian sects and Judaism – while the President is in charge of nominating the Catholic bishops of Strasburg and Metz [4]. These exceptions make clear the legislation veiled as ‘laïcité’ limits freedom of religion for Muslims while exempting Christians. Given the unilateral application of laïcité and its justification of discriminatory treatment, one can wonder if the adoption of a law prohibiting religious signs was not used to target a specific religious group. Does the law wish to exclude a group or to include it within the republican ensemble?

Moreover, the question of Islamic religious groups is associated with popular debates about immigration. The 2015 migration crisis and the recent Afghan immigration crisis have confronted France with the question of Islam. Far-right figures such as Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour justify their anti-inclusion stance by claiming that these migrants are somehow incompatible with French culture. During the 2017 presidential campaign, Marine Le Pen invoked laïcité to justify an expansion of the 2004 law to prohibit religious symbols from all public spaces. Immigration is used as an excuse to understand laïcité in a restrictive manner and serves as a justification for exclusionary policies against Muslims.

It is time to acknowledge that the consensus created through the 1905 law no longer exists. The debates between radicals and moderates that the 1905 law wished to appease are reemerging. This piece is an invitation to reconsider laïcité as a multivalent concept that is used to justify discrimination. The concept of laïcité is foundational to French identity and political system. Contradictions within the term, therefore, need to be addressed. Political parties, as well as the French society, are torn on the debate of which position religion should hold in France. Today, the debate is wrongly restricted to the position of Islam in French society. This suggests that we need to question the exceptions to laïcité that have been allowed for decades. Questioning these exceptions also means recognizing the preponderance of the favoring of Judeo-Christian traditions in the discourse around religion in France. The principle of laïcité is at the core of the current constitution: the Republic is defined as “laïque” in the very first article of France’s foundational text. Yet, emptied from its substance, the principle of laïcité needs to be redefined in light of the principles it first wished to guarantee, namely the core values of liberté, egalité, and fraternité.

Edited by Anna Hayes.

Featured image:“Liberty, Equality and Fraternity Script on a Wall” by Atypeek Dgn is licensed under Pexels.

[1] Salton, H. T. (2012). France’s Other Enlightenment: Laïcité, Politics and the Role of Religion in French Law, http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v5n4p30

[2] Gaudin, Philippe. « ‘ République and Laïcité ’: What Is at Stake in Contemporary France? » Philosophy & Social Criticism 42, no 4‑5 (May 2016): 440‑47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453716631011.

[3] Salton, H. T. (2012). France’s Other Enlightenment: Laïcité, Politics and the Role of Religion in French Law, http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v5n4p30

[4] Salton, H. T. (2012). France’s Other Enlightenment: Laïcité, Politics and the Role of Religion in French Law, http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v5n4p30