A Lawyer is Not Acceptable- At Least Not in China

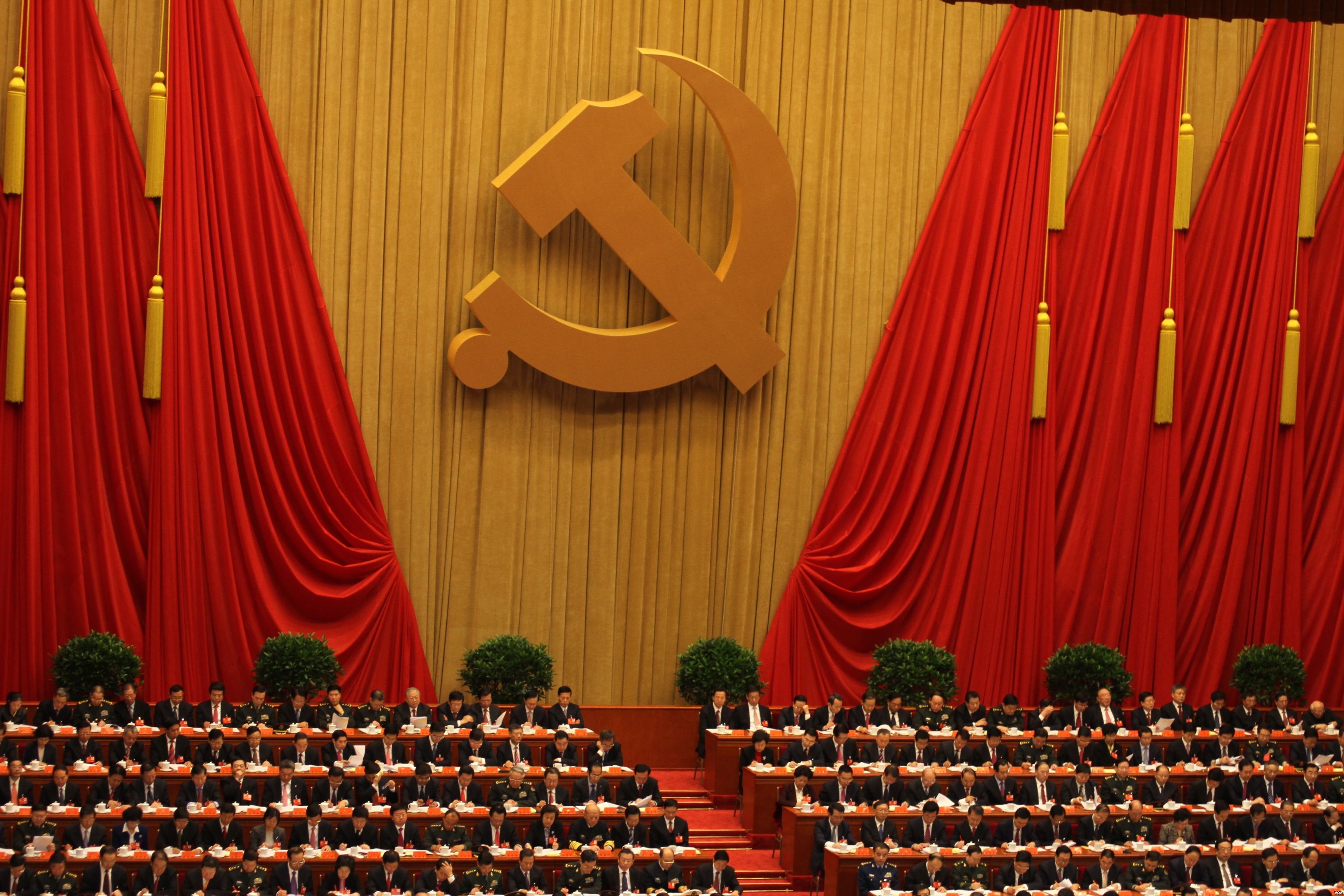

National Congress of the Communist Party of China

http://bit.ly/2skc7vL

National Congress of the Communist Party of China

http://bit.ly/2skc7vL

A world superpower equipped with one of the largest economies in the world, China has indisputably become a dominant power on the international stage. However, the largest nation in the world can hardly be seen as an equal to its Western counterparts when it comes to “fundamental rights” such as political rights, freedom of speech and right to a fair trial, just to name a few. Despite its power and respect on the international stage, China boasts some of the strictest laws related to freedoms to report or criticise politics, thus leaving doubts as to how much respect it should deserve as a leading power so blatantly willing to violate a number of rights put forth by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

In 2015, the world was appalled upon hearing the news that the Chinese government had detained over 200 human rights lawyers and legal workers. It became known as the “709 crackdown,” named after the date which it began: July 9th, 2015. At the time, the reason for these disappearances was incredibly unclear and showed a stagnation in the Chinese government’s improvements on policies of fundamental rights.

Now well into 2017, there remain a multitude of unanswered questions in regards to the actions the Chinese authorities took when holding these lawyers. Victims have consistently reported cases of abuse, misconduct and torture by Chinese authorities during the detainment. Some victims had been released while others were held without trial for an indefinite period. More recently in 2017, however, the government has been holding a series of trials, although many of which have seemed planned, coerced and reminiscent of sham trials.

Earlier in May, a prominent lawyer, Xie Yang, was convicted of subversion charges. Subversion, an offence describing an individual’s attempt to “subvert state power” or disrupt the governmental system in some way, is a serious offense in the Chinese legal system. However, its sentencing can vary greatly, depending on if accompanying charges are found. Xie Yang was not alone, as a handful of lawyers had also been tried and convicted on the same crime.

What’s more is that Xie Yang had pleaded guilty of the charges. This was unprecedented as Yang had given detailed descriptions to his lawyer of torture by Chinese authorities during his time of detention, in which he had been held for nearly two years. The situation was even more perplexing, as in January, Yang had written a letter stating that he was not guilty and any admission of guilt would be because of prolonged torture or endangerment to his family. Nevertheless, in May the trial was finally held and advertised as an open trial; yet when journalists and diplomats attempted to enter the facility, they were denied. Furthermore, Yang was denied his family-hired lawyer and was provided with a state attorney instead. In the trial, revealed through a transcript by the court, Yang had retracted all of his previous statements on torture and had warned others not to be “exploited by Western anti-China forces.” Yang’s wife stands by the claims that Yang was tortured, yet with the unfolding of the trial, it is doubtful whether she will ever receive a definitive answer.

Earlier in April, another lawyer, Li Heping, had been given a secret closed-door trial and was subsequently given a suspended jail sentence, once again on the basis of subversion charges. Heping, too, claimed he was tortured. However, he would also plead guilty to subversion charges. Mirroring Yang’s case, Heping had also been denied a family-hired lawyer. Their cases were not isolated events; since the crackdown, the same pattern of events unfolding via trials has occurred. In 2016, it seemed more popular to host televised trials in which victims openly admitted their guilt. They all had the same pattern of admitting their dangerous exploration of anti-communist ideas and some went as far to thank China’s President Xi Jinping for saving them from such a treacherous road.

http://bit.ly/2rAccOF

The trend exhibited by these trials is exactly what one would expect out of a staunch and repressive political regime, and thus it is alarming that China seems to be returning to the days of repressed speech and political sanctioning so deeply ingrained in its past. In the cloudy waves of information, the wives of the victims have become a very important source of clarity. While many families have had little to no contact with the detained, they nonetheless have made it a point to continue advocating for the rights of the lawyers. They too have suffered, with many seeking asylum in other countries for fear of losing their own freedoms should they remain in China.

For onlookers, the burning question remains: What is it about these lawyers that makes them a threat to the state? It is largely due to the cases that they choose to take on. The lawyers range from high-profile to lesser-known, but their cases are all high-risk in China, defending the rights of persecuted minority groups, political dissidents and people involved in land disputes. The issue is that for the Chinese government, protecting human rights and freedoms is often equated to entertaining “Western” and “democratic” ideals, a major red flag for the authoritarian socialist regime. As a highly restrictive nation when it comes to politics, the smallest amount of dissent is taken very seriously by a regime regime that wishes to maintain a stranglehold on the public opinions of its people. This makes it nearly impossible for any institution within China to hold the government accountable, which is where the international community would typically be expected to intervene.

However, China, an economic powerhouse, has largely been immune to strong criticism with action. This raises the question of whether China should be allowed to be immune. Undoubtedly, it is difficult and rather illogical to condemn and sanction a nation that is the “largest trading nation in the world” and thus quite indisputably necessary for the world economy. It is this factor that most likely is the main reason why the West has adopted a “laissez-faire” attitude of sorts in relation to human rights abuses in China. Nonetheless, by targeting some of its most powerful ambassadors of truth, China is stepping in an alarming direction of authoritarianism that is reminiscent of the days after Tiananmen Square in 1989. It is a factor that the world will have to face sooner or later should the world want to “eradicate the disease of human rights violations,” alluding to remarks made by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.