WHO Let Mugabe Out? Political Pressure and the Future of the WHO

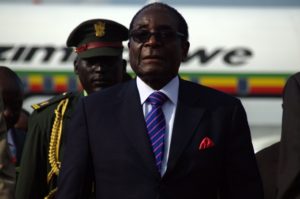

Global health stewardship and the 37 year-old rule of Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe are rarely thought of in conjunction, but for three days, the World Health Organization (WHO) believed the two went hand in hand. On October 19, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the WHO, appointed the longtime leader as a Global Ambassador for Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in Africa, shocking global health officials and the general public alike. Amid the ensuing outcry, Dr. Tedros rescinded the appointment, but not before shining a light on a glaring problem the WHO has faced for years: how to separate politics from the humanitarian work the WHO desperately needs to perform.

Global Ambassadorships (for all UN agencies) are non-salaried positions, designed to boost the profile of major initiatives. They are normally awarded to celebrities and public figures – for example, Michael Bloomberg is also a WHO Global Ambassador for NCDs. Appointing a state leader is rare, but not an inherently flawed idea. Promoting policies on an international scale is much easier if nations’ leaders are involved in the development and implementation process. The trouble with this appointment comes from the selected leader himself. Mugabe, a tyrant to many in Zimbabwe, has ruled through the collapse of the medical system in his country. What was supposed to be a universally guaranteed, accessible health care system has become increasingly stratifying and debt inducing. Patients either go without medicine or turn to neighbouring countries. Zimbabwe, which ranks at 154 out of 187 in the Human Development Index, has experienced a decrease in life expectancy and currently has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world.

How this appointment was decided is unknown. On the tail of the announcement came theories as to the rationale behind the bizarre appointment. Some believe that Dr. Tedros, the first African Director General of WHO, was trying to sate many pan-African nationalists who look to Mugabe as a leader. Others believe that WHO leadership viewed Mugabe as an influential force in the region, one who could have a beneficial impact on WHO sponsored projects in sub-Saharan Africa. This seems unlikely, however, as the Director General of WHO should be intimately acquainted with the abysmal health and human rights records Zimbabwe, and particularly Mugabe, holds. Influencing surrounding nations seems like an undesirable outcome for WHO.

This debacle negates much of the work the WHO has done to revive its reputation, initially wounded by the Ebola epidemic. Touted by many as a critical failure, the slow, uncoordinated response by the organization ran entirely counter to their mandate to “provide leadership on global health matters”. Lacking funding and staff, the WHO’s response to the epidemic lagged behind other organizations such as Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross. Margaret Chan, Acting Director General at the time, called for sweeping reforms, but it is unclear how many actually made it into common practice. WHO responses to ongoing outbreaks, such as the cholera epidemic in Yemen and the plague outbreak in Madagascar, are testing these reforms.

Funding, however, still remains a large challenge for the organization, which is itself partially to blame for the lead-footed response to Ebola, along with many other outbreaks. Under-resourced and over-extended, WHO operates with an annually diminishing budget. On top of this overt lack of capital, WHO receives money in two different ways: from members’ dues and from voluntary donations. The first subset can be spent in whichever way is deemed necessary at the time, but only comprises approximately 20% of the total WHO budget. The remaining 80% is donated money, earmarked for a specific cause. Funds cannot be shifted to deal with the most pressing matter, leaving WHO in the difficult position of begging for additional funds in the face of major crisis.

Supporters hoped that new policies, coupled with new leadership provided by Dr. Tedros, would be enough to reinstall WHO as the preeminent authority on global health emergencies. Critics, however, see the organization as a political pawn, and the appointment of Mugabe only further proves their point. In fact, WHO is an organization split between two competing visions: is it a political power whose purpose is to fulfill the needs of national governments in areas relating to global health? Or, conversely, is it simply the leading global public health agency, committed to serving those actually in need of assistance? In many ways, it must be both. WHO is a coordinating body; the middle man between government agencies and private organizations. With ever-diminishing funding and earmarks on the money it does have, the organization relies on extraneous capabilities to actually provide on the ground care. As such, emphasis on care is inherently diminished as WHO must placate a number of different organizations, political or otherwise.

Despite these structural flaws, the future of epidemic prevention and mitigation must involve the World Health Organization. Multinational forums are often infuriating, but they do have potential for reform; WHO is no exception. This was displayed in the quick revocation of the ambassador appointment: a politically motivated selection was forgone at the behest of the general public. There remains much to be done before WHO can become once again “the directing and coordinating authority on international health work”, but the timely removal of Mugabe from consideration for a good-will position does not appear to have set the organization even farther back on their quest for redemption.

Edited by Phoebe Warren