Linguistic Decolonization? Exploring Kazakhstan’s Switch from the Cyrillic to Latin Alphabet

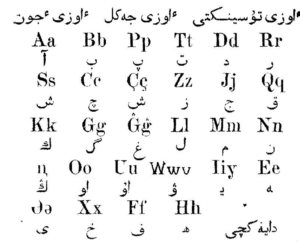

In 2006, then Kazakh leader Nursultan Nazarbayev proposed the idea of switching Kazakhstan’s Cyrillic alphabet to a Latin-based one. Fast forward a decade, and Kazakhstan has set up the National Alphabet Commission to ensure a smooth transition between alphabet systems. Historically, the country had used a variation of the Arabic alphabet up until 1929, whereupon the country briefly shifted to the Latin one. In 1940, the Soviet Union imposed the Cyrillic alphabet on all Soviet states, culturally and linguistically shifting Kazakhstan for the decades to come.

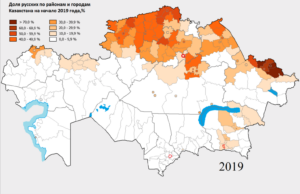

The 2016 census demonstrates how Russian is the predominant language in Kazakhstan, with 94 per cent of the population fluent in the language. This is in contrast to the rate of fluency in the Kazakh language, which rests at 74 per cent. Despite this disparity, the switch from the Cyrillic to Latin-based alphabet would be more in line with the Kazakh language’s Turkic roots. Indeed, the 1929 switch from Arabic to Latin script reflected this same spirit, part of a broader mission to encourage the Latinization of Turkic languages at the time.

It is no surprise, then, that the move away from a Cyrillic to Latin alphabet system is part of an effort for Kazakhstan to distance itself from the Soviet Union’s legacy and build a separate and unique national identity. Linguist Fazylzhanova Muratkyzy, who assisted the government in the alphabet switch, said that, “Many Kazakhs associate the Cyrillic-based script [with] Soviet control.” Although the impacts of the Soviet Union’s legacy are still felt heavily across the country today, many among Kazakhstan’s youth are prepared to embrace the changes the alphabet switch may bring. In fact, Muratkyzy’s research from 2016 suggests that in the 18-25 age range, 80 per cent of respondents support a switch to the Latin-based script.

Several reports analyzing the alphabet switch tend to focus on the economic impact such a change may bring to the country. While figures certainly do vary, the Kazakh government has estimated that it will require roughly $664 million to enact the switch, with 90 per cent of that budget needed to update the country’s education programmes with the new script. Of more interesting concern, however, are the impacts the language switch will pose to Kazakhstan’s relationship with the Russian Federation.

In 2018, President Nazarbayev’s office came under fire after it instructed Kazakh ministers and deputies to employ Kazakh in public meetings or speeches. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, most politicians in Kazakhstan have used a mixture of both Russian and Kazakh in their addresses. When the directive came down from the administration, Russian newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda alleged that this was a measure of “silent de-Russification” for ethnic Russians in the country. Of particular importance in this response, is the way the newspaper questions the future of Kazakhstan’s relationship with the Russian Federation, wondering if this language conversation could make the country “could follow the path of Ukraine” when it comes to its former Russian patron.

In the post-Soviet sphere, Ukraine has been noted for its ongoing language debate between the Ukrainian and Russian languages. The annexation of the Crimean Republic, which is widely recognized as Ukrainian territory, in 2014 was viewed by Ukraine and the West as means for Russia to weaponize Ukraine’s language politics, with Russia often legitimizing its invasion of Ukraine on the basis of protecting the Russian speakers who dwell there. Surely, the language issue in Kazakhstan has not reached the prominence it has in Ukraine, but it is nevertheless noteworthy to point out that whenever post-Soviet countries have attempted to form their own national identity, there has also been the presence of Russian aggression. In attempting to root out the cultural legacy of the USSR, post-Soviet countries have often found themselves victims of Russia’s expansionary foreign policy.

The Russian sphere of influence in Eurasia has notably declined in recent years. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has interestingly pointed out the presence of several geopolitical changes in Eurasia, ranging from generational changes, to “fading memories of a shared Soviet past,” to relationships with Western powers, as possible reasons for Russia’s more distanced relationship with the region.

The waning influence of Russia over its orbiting states has contributed to a wave of Latinization across the region, which bonds several post-Soviet countries in a fundamentally new way. On October 21, 2020, Uzbekistan outlined a language policy plan intended to better integrate the Uzbek language within the country, as well as transition the Uzbek Cyrillic alphabet to a Latin-based one. Darhan Qydyrali, a Kazakh scholar and head of the International Turkic Academy, commented on the potential of the pan-Central Asian shift, stating that, “Alphabet unity will lead to our language unity, and the language unity will lead to the unity of thoughts.” This newfound unity could facilitate a united front against Russia’s cultural colonization, thereby directly threatening the latter’s expansionist ambitions.

Even so, Kazakhstan’s incoming alphabet transition has not deterred Kazakh officials from stressing the importance of the Russo-Kazakh relationship. Political pundit Aidos Sarym noted how Kazakhstan is one of the last in the region to officially propose the alphabet switch, one reason being that many in the country fear that Russians would perceive it as a “personal blow” to the bilateral relationship. In fact, in 2014, following the Crimean annexation, Putin exclaimed how “Kazakhs never had any statehood,” minimizing Kazakhstan’s independence by taking its support of Russia for granted. For this reason, Kazakhstan, along with several other countries in the region, will continue to engage in a political tango with Russia, preserving their national interests, while simultaneously placating Putin to avoid any further geopolitical tension.

Untiled feature image is licensed under CC BY 4.0 and can be found on the website of the President of the Russian Federation.

Edited by Sarah Farb