Losing Face: The Structural Inadequacies of Australia’s ‘Pacific Step Up’

This February, New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, embarked on her first state visit to The Republic of the Fiji Islands. It was a conference overshadowed both by the global rise of COVID-19 and the continued impacts of climate change on the region. Ardern declared that these “are borderless challenges and they demand a collective response,” committing to assist the Pacific on both counts. Her example has delivered an implicit challenge for regional powers to act similarly—powers like Australia.

For a country that has pledged to upscale its involvement in the Pacific, Australia has appeared reluctant in addressing the region’s crises. While New Zealand’s Pacific Minister, Aupito Sio, has made regular media appearances responding to COVID-19 in the region, his Australian counterpart, Alex Hawke, has been conspicuously absent. On another front, while Jacinda Ardern’s climate policy was commended during her Pacific visit, the Fijian Prime Minister, Frank Bainimarama, also used the opportunity to “demand” climate action from Australia. These two incidents highlight systematic inadequacies in Australia’s Pacific engagement, demonstrating a governmental inability to grapple with the short- and long- term problems which concern the region most.

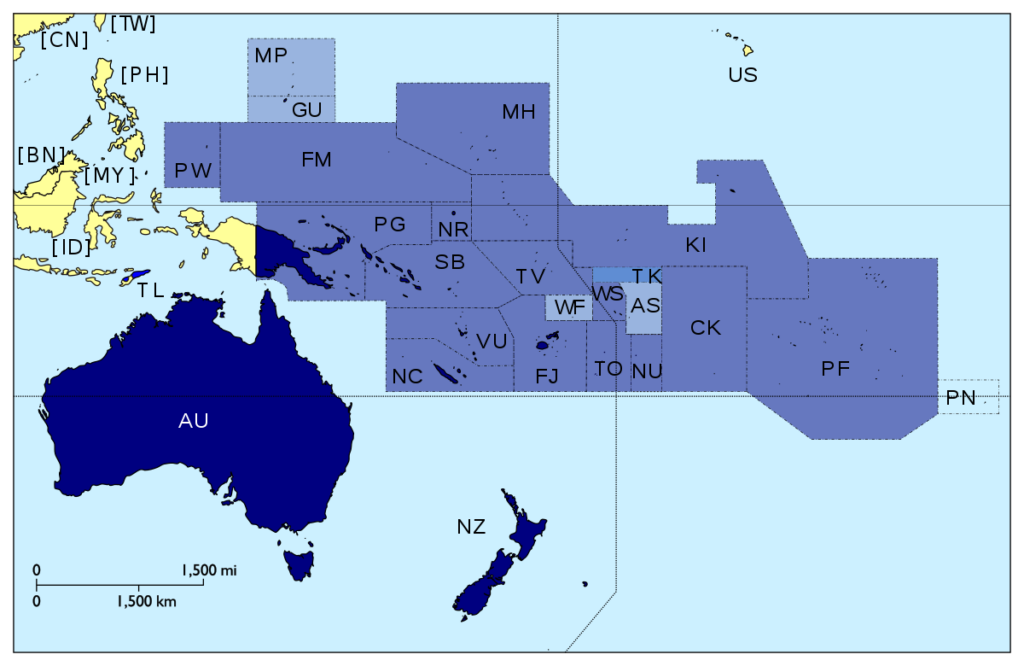

In 2019 Scott Morrison signalled a clean break in Australia’s Pacific policy, trading Turnbull’s “step change” rhetoric for that of a “step up”. Morrison committed to the dramatic upscaling of Australian involvement in the Pacific Islands, gold-plating this commitment with a regional infrastructure donation to the tune of two billion dollars. Warmly referring to the Pacific strategic zone as “our patch… our part of the world,” Morrison, like his predecessor, promised favourable redistributions of the foreign aid budget. His aim was to secure a zone that the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper called “vital to our ability to defend… our borders” from growing Chinese regional influence. His success, one year on, has been questionable.

Four official state visits since 2019 and the majority of Australia’s ailing foreign aid budget have gone into Morrison’s attempt to re-assert Australia’s regional soft power. Yet, at the last meeting of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), Former Kiribati President Anote Tong labelled Australia the “worst of two evils” in comparison with China. In addition to its abundance of cheap debt opportunities, China has proven attractive for its dramatic actions against climate change, a topic of high priority in the Pacific. This became evident last year when the Solomon Islands joined China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road infrastructure project, ignoring Australia’s $250 million incentive to keep out. Ostensibly, it would appear, Australia’s Pacific step-up has been inadequate.

The twin crises which confronted Ardern on her Fiji visit have both proven telling examples of Australia’s patchy engagement with the Pacific. In the first instance, Australia’s limited response to COVID-19 in the region can be seen as a microcosm of its failure to deliver targeted assistance to the Islands. Australia has been called “missing in action” in its Pacific coronavirus response, with the federal opposition declaring that “much more needs to be done.” Despite contribution to the WHO’s million-dollar Pacific Response Plan, analysts have predicted a significant shortfall in Australia’s contribution. Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic threaten more than just public health in the Pacific. In March, the PIF Observer Mission to Vanuatu’s 2020 general election was recalled out of containment concerns, potentially jeopardizing the state’s democratic proceedings. Viewed on this level, COVID-19 poses a far greater threat to the region than it does to Australia, heightening the need for a significant response. Such a response has not been forthcoming. On issues like COVID-19, to borrow from Jacinda Ardern, “Australia has to answer to the Pacific.” Effective crisis management is vital to securing influence in the region, and yet it has not been delivered under Australia’s current engagement model. Broad-brush infrastructure investment, while valuable, cannot be a substitute for genuine engagement on the short-term issues that Pacific Islanders see as priorities.

Australia has also been called disingenuous in its response to the long-term regional issue of climate change, a further strike against its geo-strategic standing. The problem, articulated by Anote Tong, is that Australia’s contributions to the Pacific’s environmental response have been “dictated by the coal industry in the background.” As the world’s biggest coal exporter and a country that is far behind in reaching its Paris Climate Agreement targets, the credibility of Australia’s commitment to helping Pacific Islands tackle global warming has been limited. Rising sea levels associated with greenhouse emissions have had a disproportionate effect on island nations worldwide. Dangerous weather and sinking infrastructure have already seen the emergence of a new class of climate refugees, with Kiribati citizens claiming asylum abroad as early as 2016. The Australian response to these problems has been considered hypocritical. Despite offering $500 million in climate adaptation funding to the Pacific, Australia has continued to greenlight domestic fossil fuels projects like the Adani Carmichael coal mine, directly contributing to the crisis. In this context, Fiji’s Prime Minister has called Morrison “very insulting and condescending” in his attempts to assuage climate fears with funding. To gain favour in the Pacific, Australia’s response to climate change must be genuine.

In a mid-March interview with the ABC, the opposition spokesman for the Pacific noted that “if we’ve lost the public face of the Pacific Step-Up, it’s pretty hard for the rest of the Pacific to engage with us.” Scott Morrison has made the Pacific a foreign policy priority. He has failed, however, to tailor his response to Pacific audiences. Australia’s ability to ‘regain face’ in the region rests on two pillars: effective response to short-term regional priorities like COVID-19, and convincing commitments to tackle long-term problems like climate change. If Ardern’s successful Fiji visit this year has demonstrated anything, it is that Australia, like New Zealand, must act on these two fronts. No degree of additional infrastructure expenditure can allay the need for an issues-based approach to foreign aid. If Australia’s policy in the Pacific is to have teeth, it must be nuanced, and it must be genuine.

Featured image by Adli Wahid on Unsplash

Initially published in the Kosciuszko Review, this article is published in the MIR through a collaboration between the two publications.