Lost in Trans-lation: Cultural Perceptions of Queerness in Iran

“In Iran, we don’t have homosexuals, like in your country,” declared President Ahmadinejad to an audience at Columbia University in 2007. This statement sparked instant commotion in the audience and a wave of international condemnation, but it also shone a light on often-invisible queer Iranians. Of course, Iran has a deep history of homosexuality—from the 11th century Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, who alternated the gender of his lovers seasonally (women in the winter, young men in the summer), to centuries of Persian poets who have chronicled queer relationships. While homosexuality has survived and thrived under different names in Iran’s history, it has always existed.

Under the current Islamic Republic of Iran, homosexual intercourse is punishable by death. Iran is one of 73 countries that criminalizes homosexuality, and is one of 10 where the penalty for being gay is execution. Religious fundamentalists in Iran, however, accept the notion that an individual may be born in the “wrong body,” (where one’s sex does not match one’s gender identity). Indeed, the state will loan transgender citizens money for sex reassignment surgery and guide them through the transition. In a country where homosexuals are violently targeted, gay citizens are pressured into having sex reassignment surgery. Changing one’s sex is presented as the medical solution to homosexuality. While the government’s acceptance of transgender people is positive, it is obviously problematic for cisgendered homosexuals who have no desire to change their sex. Additionally, the system excludes any fluidity for Iranians who don’t identify with the gender binary. While the government does not officially enforce gender reassignment surgery on homosexuals, the coercive social pressure can be overwhelming.

When the Shah dynasty was overthrown in 1979, a wave of moral puritanism swept through Iran. The newly founded Islamic Republic sought to cleanse immorality through public executions of homosexuals, prostitutes, and drug addicts. Dress codes were strictly enforced and transgender identity was relegated to the shadows. This changed in 1987, when Ayatollah Khomeini (the founder of the Islamic Republic) met with trans-activist Maryam Khatoon Molkara. Ms. Molkara’s plight of being a woman trapped in a man’s body apparently moved the Ayatollah. Within half an hour of their meeting, Ms. Molkara was given a black chador (an obligatory symbol of femininity in the Islamic Republic) and was legally recognized as a woman. Following this meeting, the Ayatollah issued a fatwa allowing for gender reassignment surgery—a decision that changed Ms. Molkara’s life and set a precedent for transgender rights in Iran. Today, over 300 sex reassignment operations are performed annually in Iran, which is more than any other country except Thailand. The operation’s acceptance and popularity is particularly odd when compared to the institutionalized homophobia that oppresses gays. In contrast to Iran, much of the traditional attitudes in the Global North lump transgender individuals into the same sinful category as homosexuals. As LGBTQ rights have steadily progressed in the Global North, gay rights have taken priority in the form of marriage equality and increased normalization for decades, while transgender rights have progressed at a much slower pace—as shown by North Carolina’s discriminatory bathroom bill, to name the most recent example. We must therefore wonder: why is the opposite true in Iran? Why is it politically illegal and socially taboo to be gay in Iran, but acceptable to be transgender?

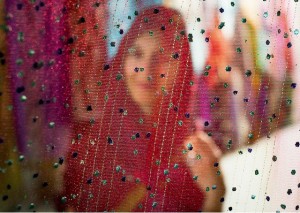

Iranian culture is strictly segregated by the gender binary. Public transportation in Tehran is partitioned so that men and women sit separately. Those who trespass the clear boundaries of masculinity and femininity are socially punished. Homosexual men, perhaps, are viewed as inherently feminine and therefore are transgressing this binary, while transgender individuals leave these social codes intact and therefore are not seen as a threat. In fact, transgender Iranians have the potential to fortify the legitimacy of this binary.

Within the segregated spheres of gender behaviour, relationships between people of the same sex in Iran have distinctive social rules. One student at McGill, who wishes to stay anonymous for security reasons, describes his experience as a queer man in Iran: “The state is not the biggest vector of oppression in Iran towards queer people. Social segregation of the sexes is so strong that homosocial spheres are very developed—to the point that we wouldn’t understand in Europe.”

The student described witnessing two men on public transportation touching each other’s legs and grazing their hands against the other’s neck. The student said this behaviour would be seen as “very sensual and homoerotic here. Whereas in Iran it’s just friendship.” To outsiders, these homosocial displays of affection may be shocking, but, in actuality, merely reflect differing attitudes around gender and sexuality. This demonstrates once again how significant culture is in scripting and shaping sexuality and gender behaviours.

In western culture, physical and emotional affection between men is often viewed as intrinsically gay. Heterosexual men will sometimes compliment each other and physically embrace before adding the heterosexist caveat “no homo.” This is particularly striking when juxtaposed against homosocial relationships in Iran. Indeed, we would generally consider Iran a more homophobic society, and yet heterosexual men are afforded more freedom for “gay behaviours,” such as affectionately holding hands. This demonstrates a paradox in Iranian society, where Iranian homosexuality is simultaneously more oppressed and yet more emancipated.

Perhaps the greatest divide in Iran, beyond the segregation of gender, is the chasm between the private and public sphere. Vast numbers of Iranian youth live wildly different lifestyles in the seclusion of their homes. An increasing number of Iranians have sex before marriage, while maintaining the façade of religious conservatism in public. Indeed, the Islamic Republic’s attitudes towards alcohol and gender are quietly subverted everyday. Social attitudes towards homosexuals, however, are entrenched far deeper than the state, and thus would be slower to progress should the regime transition. It appears that while a sexual and social revolution may be brewing underneath the surface of Iran, a queer revolution is distant.

Through uncovering Iranian cultural attitudes on sexuality, we can, by detour, uncover truths about our own understanding of sexuality. Iran’s paradoxical acceptance of transgender people and criminalization of homosexuals can destabilize our western understandings of an essential gender and intrinsic sexuality. Indeed, Iran demonstrates that what we often conceive as natural is in fact culturally constructed. Perhaps, contrary to orientalist tropes of Iran—which depict Iranians, especially women, as passive victims waiting to be liberated by the West, Iranian conceptions of gender could liberate us. Perhaps the West could learn from homosocial bonds and thus be emancipated by Iran. Of course I am not suggesting that we oppress sexual minorities, but rather, that we should reevaluate gender and listen to other cultures as we seek new possibilities for what it means to be queer.