Macron’s Victory Won’t Thwart Populist Demagoguery

At a quiet dinner hosted by former presidential aide Jacques Attali in 2008, then Socialist Party First Secretary François Hollande asked a young investment banker if he had any aspirations for political office in the future. The investment banker was ambivalent, claiming that he did not want to be obligated to public affairs and would rather be a behind-the-scenes advisor.

Around this time Hollande’s own political aspirations were on the downturn. The Socialist Party decided to nominate Ségoléne Royal for the 2007 French elections, and when she lost they placed their support on then IMF Managing Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Despite all of this, the banker continued to support Hollande, cementing their personal relationship. When a sex scandal spoiled Strauss-Kahn’s campaign, Hollande suddenly became the Socialist Party’s candidate for the 2012 elections, and he wanted advice on how to address France’s economic issues.

The banker then assembled a group of top economists at La Rotonde and produced a 200-page economic plan for the Socialist candidate. A pro-industry, neoliberal reform proposal, this was a sharp contrast from the Socialist Party ideology that Hollande ran under. Moreover, this economic strategy was contradictory to Hollande’s campaign rhetoric of combating the financial world and taxing-the-wealthy. Jean Pisani-Ferry, an economist who attended these sessions at La Rotonde, claimed that the document laid the foundation for Hollande’s pro-business turn during his presidency. Hollande hired the investment banker to be his deputy chief of staff and eventually, his Economic Minister. Unable to balance competing interests from the Socialist Party, the electorate, the EU, and his own cabinet, Hollande would be received with widespread unpopularity, forcing him to abstain from running for reelection and leaving the presidency in disgrace.

Meanwhile, the very same banker turned Economic Minister formed a new political party, En Marche! (Forward!), describing himself as “neither of the right nor the left” with a goal of modernizing the French economy. At this point, the banker comes into full view. This man is Emmanuel Macron, the incoming President of the Republic of France. Despite experiencing a turbulent campaign, Macron rocked the very foundations of French politics, marginalizing both the Republicans and the Socialists and halting Marine Le Pen’s populist movement in its tracks. Macron has won the presidency in the second round of the French elections, defeating National Front opponent Marine Le Pen by a margin of 66% to 34%. At 39, Macron is the youngest leader of France since Napoleon.

Both Macron and Le Pen tap into frustration from voters, with a sluggish economy exacerbating issues such as youth unemployment, a lack of job security, high taxes, and heavy regulations. Furthermore, terrorist attacks from religious extremists have left citizens uneasy, further exposing a rift between the nation and its diverse Muslim community. However, despite examining the same issues, Macron and Le Pen have drastically different diagnoses and solutions for France’s longstanding problems.

Marine Le Pen has led the National Front since 2011, taking the job from her father Jean-Marie Le Pen. Le Pen’s National Front stands for a heightened sense of French nationalism, political isolationism, and economic jingoism. She wants to exit from the European Union and restore the Franc as France’s national currency. However, Le Pen also firmly believes in the existence of a link between immigration and militant Islamism. Had she been elected, Le Pen would have “expelled foreigners who preached hatred” in France and strip dual-nationality Muslims of their French citizenship. Le Pen had hoped to reduce immigration by 80%.

It goes without saying that quite a bit of Le Pen’s campaign rhetoric is a cause for concern. She has attempted to package the persuasive notion of authoritarianism and xenophobia under the guise of a modern, protectionist government, and her intolerance towards certain ethnic groups is worth taking note. However, a Macron presidency fails to address the issues that created the political momentum against globalization and the European Union (EU). Despite his alleged claim throughout the campaign that he is a political outsider, Macron is anything but. His campaign stands for a system that is inherently flawed, and he is just its fresh face.

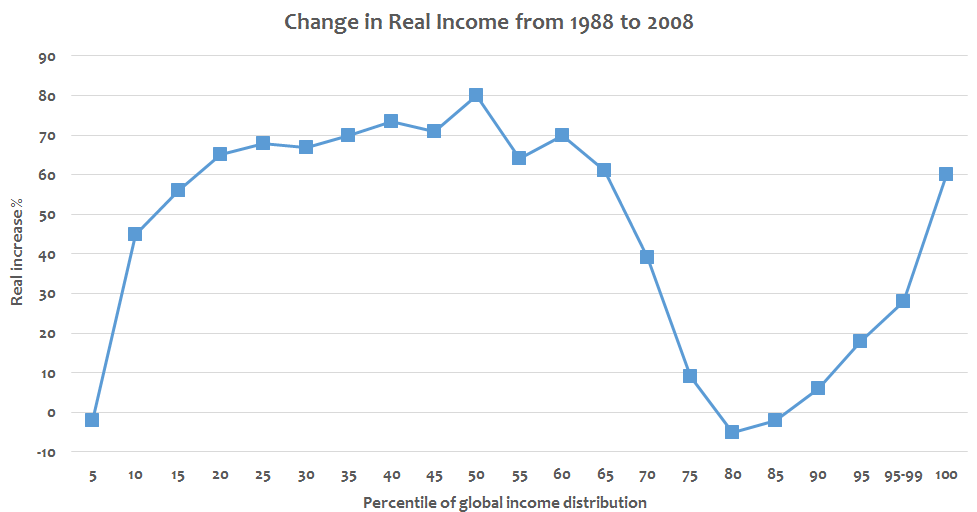

The very structures that Macron stands for, neoliberalism and globalization, are what is in dire need of change not only in France, but in the entire Western world. Globalization in this sense is the methods in which our contemporary capital-driven global economy redistributes the supply of labour rather than the social and cultural exchanges that occur due to increased interconnectedness. On one hand, this has allowed many corporations and nations to achieve new levels of economic growth and provided employment to the lowest classes, allowing many to escape from poverty. For consumers in advanced nations, it has created a downward pressure on the cost of supply. Somewhere along the way, however, the global middle class have been left behind. This phenomenon is illustrated by economist Branko Milanovic’s Elephant Curve. While we may have seen a rise in wealth in many countries, the distribution of this wealth has created little to no gain for people in the 75th to 90th percentile of global income. Those who have suffered the most from globalization are the very individuals who voted for Le Pen and many other isolationist leaders and movements in North America and Europe.

Economist and Oxford University Professor Kevin O’Rourke outlines this hypothesis in his work of the Davos Lie: outsourcing activities reallocate labour throughout the globe, but it is not low skilled service jobs or abstract high skilled jobs that are leaving Western countries; it is middle-ranking routine work, such as manufacturing. When substantial sections of the community experience the lowering of living standards, they will object. This is a driving force as to why the stagnating global middle class is retaliating against free movement of trade and immigration and backing candidates such as Trump and Le Pen. Similarly, Brown University Professor Mark Blyth calls this movement “Global Trumpism.” For decades following World War II, nations have targeted full employment at the expense of wealthier classes, creating inflation. In response, creditor classes in these nations pushed for the deregulation of finance and integrated our global economy as we know it today. The free movement of labour under neoliberal globalization has stripped power away from workers. In turn, this means labour unions lose their influence, and workers are unable to make demands for fear of outsourcing.

On top of this, France’s membership in the European Union only further exacerbates the disenchantment amongst its citizens. One important aspect to consider is how France uses a centralized currency in the Euro. Under the European Central Bank’s monetary policies and its Fiscal Compact, there is little primarily consumer-based economies like France can do when they run into a deficit. This is because a fiscal balance is interconnected with the current external account balance and the private sector savings-investment balance. Lost? This can all be explained with a simple algebra formula:

This is written as the sum of savings (S) minus investments (I) and taxes (t) minus government spending (G) equals exports (X) minus imports (M).

When a country like France imports more than it exports (in such a way that its current account, or X – M, is negative), then either its private sector savings or government balance is running in the negatives as well. In the economic system implemented by the European Union, this is disastrous. In a shared system currency, if someone is running a surplus, then others must naturally be running a deficit. As other nations like Germany increase their exporting power, France’s current account deficits run deeper into the negatives, and it is forced to address this issue under the Fiscal Compact by permanently downsizing its economy. France and its people are unable to use protectionist policies or devalue their currency to protect themselves from the E.U.’s long term problems. Interestingly enough, it was Le Pen and far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon who advocated for these changes. For these reasons, it is still exceedingly concerning that Macron proposes no real changes to the current system.

Ultimately, nothing from his platform is going to address the real problems plaguing the European Union. Those who feel slighted by the EU and globalization are not going to be satiated, and as France’s economic issues magnify, their numbers will only grow. When France and Europe faced the xenophobic far-right populist movement, it had to stand by the centrist Macron. In return, as he starts his presidency, Macron will need to stand on his own merits.

The featured image “Emmanuel Macron” by Jacques Paquier is licensed under CC BY 2.0.