“Magic Mushrooms”: New Hopes in Mental Health Treatment

In 2018, Canada made headlines when it became the first G7 nation to legalize cannabis for medical and recreational use. This development came as public opinion began to shift, and it became clear that criminalizing cannabis was only reinforcing racial and class discrepancies. In another landmark decision, Federal Minister of Health Patty Hadju approved the usage of psilocybin, also known as magic mushrooms, for cancer-associated end-of-life therapy in August 2020 for four Canadian individuals. Shortly after, a handful of Canadian researchers were also granted exemptions to use psilocybin for research purposes, illustrating the growing interest in psilocybin’s potential to treat mental health illnesses, like treatment-resistant depression, anxiety, PTSD, and substance use disorder.

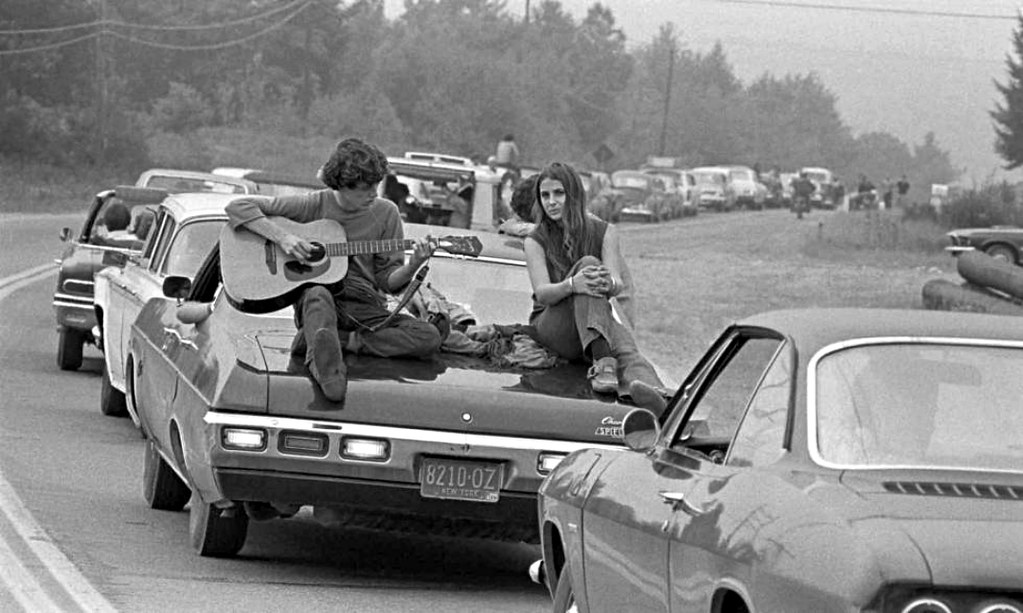

Research on the therapeutic potential of psilocybin, and psychedelics in general, is not new. Before psychedelics became more mainstream and were adopted by the counterculture movement in the 60s, they were mostly found in the hands of doctors for research and treatment of mental health disorders, with thousands of patients receiving “psychedelic psychotherapy” in the 1960s with promising results. However, the rise of these mind-expanding agents was short-lived, as Nixon’s War on Drugs in the 1970s effectively put an end to all research on psychedelics.

In Canada, psilocybin was made illegal in 1974. In 1996, psilocybin and other hallucinogens were classified as Schedule III drugs under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. This meant that the sale, production, and possession of these drugs were prohibited unless otherwise authorized for research or clinical purposes under “Section 56” exemptions. A modern expansion of these exemptions occurred in 2017 when two churches in Montreal were granted permission from Health Canada to legally use ayahuasca, a powerful hallucinogen integral to the Santo Daime practice of meeting the divine. However, Health Canada’s recent approval of psilocybin use is the first case of hallucinogen approval for medical use.

After a 30-year hiatus, interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics has slowly re-emerged. Most notably, a team at John Hopkins University published a groundbreaking paper in 2016 with overwhelmingly positive results. In end-of-life cancer patients with symptoms of depression, anxiety, or both, psilocybin was associated with an increase in quality of life and a significant reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety, with effects persisting after six months in most patients. Aside from depression and anxiety, researchers are also investigating psilocybin and other hallucinogens for the treatment of substance use disorder, PTSD, OCD, and eating disorder.

In August 2020, TheraPsil — a non-profit coalition of healthcare professionals advocating for therapeutic access to psilocybin — supported the exemptions of four Canadians battling end-of-life distress. “We’ve started by helping individuals with a terminal diagnosis as the research regarding psilocybin-therapy for this cohort is most robust, and these individuals are in urgent need,” says Holly Bennett, Director of Communications at TheraPsil.

With this revival of research into the power of psychedelics, scientists have employed modern, innovative ways to collect data from users of these drugs. Thomas Anderson, Ph.D. candidate, Director, and Co-founder of the Canadian Centre for Psychedelic Science, recently published work on psychedelic microdosing in 2019. “We did our first study mostly on Reddit, asking people and focusing on r/microdosing subreddit, and r/nootropics section has a lot of microdosers,” says M. Anderson. Given the legal status of psilocybin, researchers were limited in the work they could do. However, since 2020, as Health Canada increasingly grants researchers legal exemption to use psilocybin, researchers have a greater ability to study psilocybin. “Asking the existing [Reddit] communities provides an opportunity to create new hypotheses that we can test properly in a controlled lab setting,” says M. Anderson. He hopes to study the benefits and drawbacks of psilocybin microdosing in a clinical trial after receiving Health Canada approval.

Research in psychedelic psychotherapy is important, as it could potentially revolutionize the field of psychiatry. For example, it is estimated that approximately 30 per cent of patients are treatment-resistant with conventional therapies for major depressive disorder. However, psychedelic psychotherapy could yield significant improvements in the quality of life of these patients. Most of the evidence is currently anecdotal or from smaller studies requiring further rigorous studies, which may take some time. M. Anderson explains, “We need to do the science properly so that we don’t get pushed back in the future. […] We don’t need fast science, we need good science.”

Although the potential benefits of psychedelic therapy were known since the 1960s, major challenges have impeded new studies. Aside from bureaucratic hurdles from strict anti-drug regulations, M. Anderson explains that another major obstacle is money. “We’re not short on ideas of great studies, what we’re short on is money,” he clarifies. Since psychedelic compounds cannot be patented, pharmaceutical companies have no incentive to invest. Government funding is also scarce, and in most cases, non-existent, given the controversy and negative public perception of psychedelics. Thus, most funding is currently limited to the generosity of private donors and philanthropists.

With Health Canada’s increasing support for medical research on psilocybin, is the next step decriminalizing psilocybin? Not quite yet, as per a spokesperson for Minister Patty Hadju. However, Health Canada is considering making it easier for individuals requesting access to psilocybin to treat patients with serious or life-threatening conditions. In 2013, under Stephen Harper’s conservative government and its anti-drug policy, Health Canada banned individuals from accessing heroin — and other drugs, including psilocybin — through the Special Access Program. This program allows physicians to request drugs unavailable for sale, such as illicit drugs, for patients with a life-threatening condition for compassion use. However, with a less tough stance on drugs, the current Trudeau administration is considering amending the Special Access Program to allow healthcare professionals to request psilocybin for patients. For the moment, however, the only current legal pathway to access psilocybin is through an application invoking “Section 56,” which can be an arduous application process.

So far, only a handful of Canadians have successfully received legal exemptions. “To date (March 9, 2021), we have supported 27 Canadians in accessing legal psilocybin therapy through approved Section 56 exemptions, including some patients who are terminally ill but have active non-terminal cancer or are in remission. We have also helped 19 healthcare professionals in applying for and receiving approved Section 56 exemptions so they may use and possess psilocybin as part of their professional training in psilocybin therapy,” indicates Holly Bennett from TheraPsil. Some of these first Canadian patients who received such exemptions, such as Thomas Hartle and Mona Strelaeff, have described their positive experiences to the media.

Given the recent success of psilocybin in Canada, is it reasonable to envision a future where psilocybin is legalized, not only for medicinal use but also for recreational use? “There’s some space to talk about recreational use, but that’s going to be much further down the line. It’s much easier for the next 5–10 years to pitch medical. That’s how cannabis was approached in Canada as well. It’s pitched medical, and then there’s this expansion [to recreational],” says M. Anderson. For now, the next step is really to focus on research to establish the role of psilocybin — and other hallucinogens — in mental health treatment.

Featured image: “psilocybin” by D.C.Atty is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Teresa Tolo