Making a Battleground State: The Future of the Lone Star’s Electorate

The possible cause of Texas as a swing state

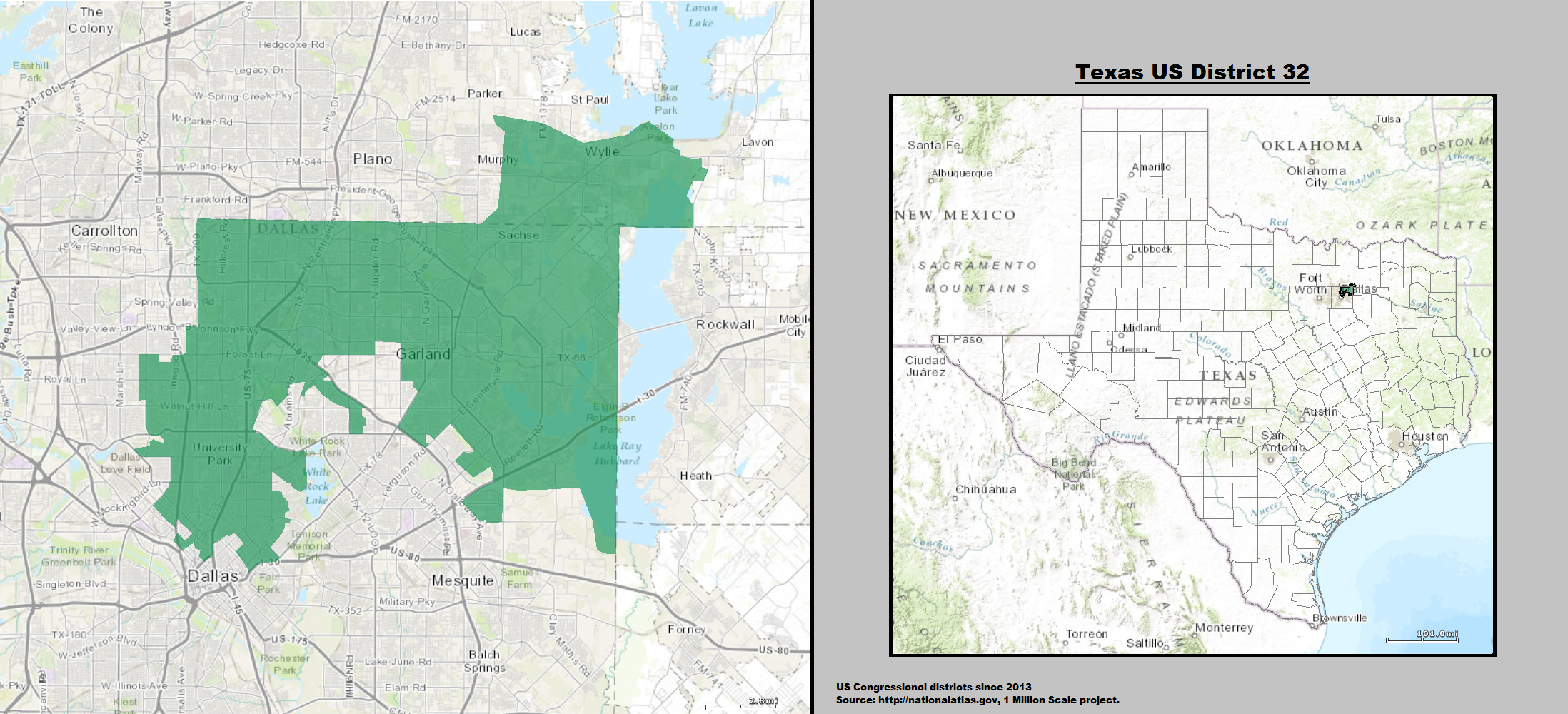

Your hands are sticky from a melted popsicle and sore from clapping for the fifth or sixth patriotic display of the afternoon. As you stand near University Park’s colonial-style town hall, you smell the freshly-cut grass, the hot plastic of inflatable slides, and the sulphurous odour of prematurely ignited fireworks. The 4th of July always draws a crowd, and this year is no exception. Still, the overarching sense of patriotism is destabilized when Colin Allred — newly elected representative of Texas’ 32nd Congressional District — moves to speak. No one breaks the silence, but the confusing imagery of a Democrat mounting the stage instead of a Republican for the first time in 22 years says enough.

Something changed between the 2016 and 2018 elections when veteran Republican congressman Pete Sessions lost his seat to a Democrat, concluding his 1997 to 2019 tenure in office. Allred did not go about his campaign by appealing to the old money and conservative values of Dallas’ wealthiest, concentrated in the district’s southwest corner. Instead, the secret to his success lies with the citizens of Richardson and Garland at the heart of the 32nd.

Since 1980, Texas’ electoral votes belonged to the Republican presidential candidate, even as the electoral map became more and more divided over time. Ostensibly, Texas is the poster child for Republicanism: rural populations, firearm deregulation, and a proud nationalist mentality toward Texas and the US. These traits have manifested themselves in creating one of the 21 Republican state “trifectas,” wherein the Republican Party holds both bodies of the state legislature and the Governor’s Office.

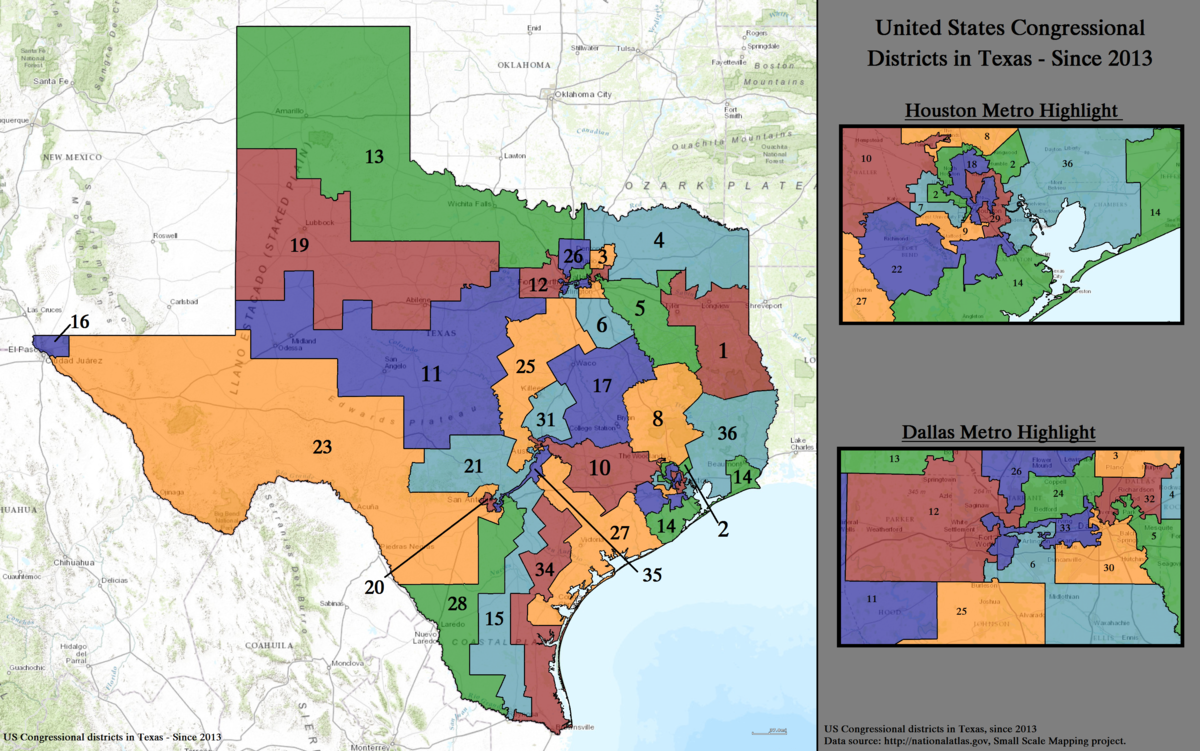

No matter how deeply red a state is, large urban areas and universities generally lean more to the left, especially in cities where these two enclaves overlap. According to Jonathan Rodden, areas with population densities above roughly 1,560 people per square mile all but guarantee Democratic majorities. As Rodden explains in his book, Why Cities Lose, population density is an indicator correlated with increased education and invention rates. So, the problem for Texan cities is partisan redistricting, which secures Republican victories by creating electoral districts that encompass rural and urban constituencies.

The implications of partisan redistricting are difficult to classify. Metropolitan areas (the regions urban congressional districts carve into instead of purely urban or rural areas) have difficulty crossing the necessary threshold, with Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington scraping out 722 people per square mile as Texas’ second densest metro area. For reference, the New York Tri-State area clocks in at 2,157 people per square mile, just below Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana. However, Dallas boasts a population density of 3,216 people per square mile within its city limits, well above the necessary figure. Ultimately, partisan redistricting dilutes the Democratic vote share by distributing the large populations of urban areas amongst the surrounding suburban sprawl and decreasing the population density of congressional districts.

Urbanites in El Paso, Austin, Dallas, and Houston began visibly moving to the left in 2016, facilitating Collin Allred’s and Lizzie Fletcher‘s victories in Dallas and Houston, respectively. Of course, there were existing Democratic congressmen and women prior to these new additions (thirteen of the thirty-six are currently blue) but these two victories are possibly indicative of change beyond the colour of their districts. Of the thirteen districts with Democratic representatives, eleven have maintained Democratic incumbency since the 2010 census or earlier; the two that do not follow this trend are Allred’s 32nd and Fletcher’s 7th.

Now, we return to the original question: Why did the 32nd switch parties in 2018? What could explain the thin margin of Senator Ted Cruz’s victory over the popular Beto O’Rourke by only 2 per cent, or President Trump’s victory in Texas by the lowest margin since Bob Dole in ’96? Richardson and Garland — the towns occupying the middle body of the horse-shaped 32nd district — present a new Democratic environment that could indicate the imminent dislodging of Texas from a Republican majority. Demographically, the 32nd is nothing special. Their median ages hover around the same as the statewide median of 34. Both consist of significant immigrant populations — but nothing noteworthy when compared to the rest of the state. The percentages of whites in the district’s large cities of Dallas, Richardson, and Garland in 2018 were higher than the state average just three years prior. Where this population lives, however, explains this change: the district’s rural population was essentially wiped out since 2010 (from 6.9 per cent to just 0.2 per cent), and 72 per cent of the state population now lives in “urbanized metropolitan areas” that are “growing dramatically.”

Texas is becoming less of a dichotomy between urban and rural areas as urban sprawl yields suburbs and exurbs en masse. These suburbs are composed of an increasingly prosperous and educated middle class — therefore, one more willing and capable of voting — with Texas’ large immigrant and minority population at its core. The ongoing development of this class – and its surroundings – has used the court system to make voting more accessible for all Texans, especially those who may have begun to take more of a personal stake in politics over the past four years. Immigrant and minority populations watch the land around them develop rapidly, decreasing the ratio of the population living in developed to undeveloped land. They have discovered within themselves a greater ability and calling to vote through recent economic and educational development. It will therefore be up to these large sections of the Texan population to swing the state in the direction of their choosing.

In the past, the party in control of Texas’ rural expanses received its electoral votes. Now, it seems, the party that controls the growing suburbs will have a good shot at commanding the Lone Star State. As suburbs continue to develop economically and grow in size and population, they serve as a volatile middle ground. They are not dense enough to be reliably Democratic, nor are they rural enough to be overwhelmingly Republican. While suburbs are usually Republican-leaning, the evidence above suggests that suburban Texas is encroaching on urban levels of economic development and population density, improving educational and political opportunities. A perfect storm would be required to have Texas on Biden’s side in the upcoming Presidential election, especially in light of the ongoing pandemic. Still, it’s no secret that Texas has become less entrenched in the Republican camp since 2016. Texas may not go blue in 2020, but these trends show no signs of stopping over the next decade.

It’s been a hard four years for the Republican party. Between a polarizing party leader and a global pandemic that shot the national unemployment rate above 14 per cent in April before steadily receding to 8 per cent by October, much of the work (both economic and social) done before COVID-19 was undone in the precarious moments preceding the upcoming general election. Democrats winning districts seated within Texas’ large metropolitan areas is no anomaly, leaving the volatility to the quarter of the citizens that exist outside of urban counties. Winning the rural population has been the key to the Republican incumbency of the past four decades, but accessing and mobilizing the developing suburban population in suburban-rural areas may be the hinges on which Texas will swing. This article on indicators of a swinging Texas has focused largely on the possibility of a Democratic victory, but that is only because of the implication that a Democratic Texas is a different Texas. Once the state establishes a political fluidity, it may very well become a battleground worth 36 electoral votes (or more): the most-valuable in the union.

Featured Image: “Texas,” by Noé Alfaro is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Edited by Luca Brown