Marx meets the Free Market: Why Market Socialism is the way forward

Although seeing Karl Marx on a banknote may be ironic, combining the beliefs of Marxism and Capitalism gives us Market Socialism.

Although seeing Karl Marx on a banknote may be ironic, combining the beliefs of Marxism and Capitalism gives us Market Socialism.

Capitalism, our current state of socio-economic affairs, has given us a lot: economic growth, innovation, technological progress, and choice. However, it has also given us something more terrifying than that, too: economic crises, increased income inequality, poverty, lack of health & sanitation, and lack of opportunities for those who wish to escape the poverty trap. Conservatives and Liberals point to its benefits and call for privatization, lower corporate taxes and spending cuts; Communists point to its flaws and call for seizing the means, increased spending, and nationalization. But both answers lead to more problems — problems of trade-offs not only related to economics, but also related to ethics. There is however, a solution. A solution that satisfies capitalists & socialists; a solution that satisfies economics & ethics; a solution that satisfies Smith & Marx. That solution is Market Socialism.

Market Socialism is a political belief which states, just as Marx advocated, that workers should socially own the means of production. Profits should be distributed amongst those who work, and any decisions to be made must be made democratically by each worker-shareholder. This socialist framework of operation is to be then adapted to the forces of the market, where instead of government-controlled central planning or nationalization, the market dictates the demand & supply for the goods produced. Summed up, Market Socialism advocates for collective ownership in a free market economy. Market Socialism can be analyzed with 3 lenses or scales: small-medium enterprises or SMEs (small), conglomerates (large), and national (economical).

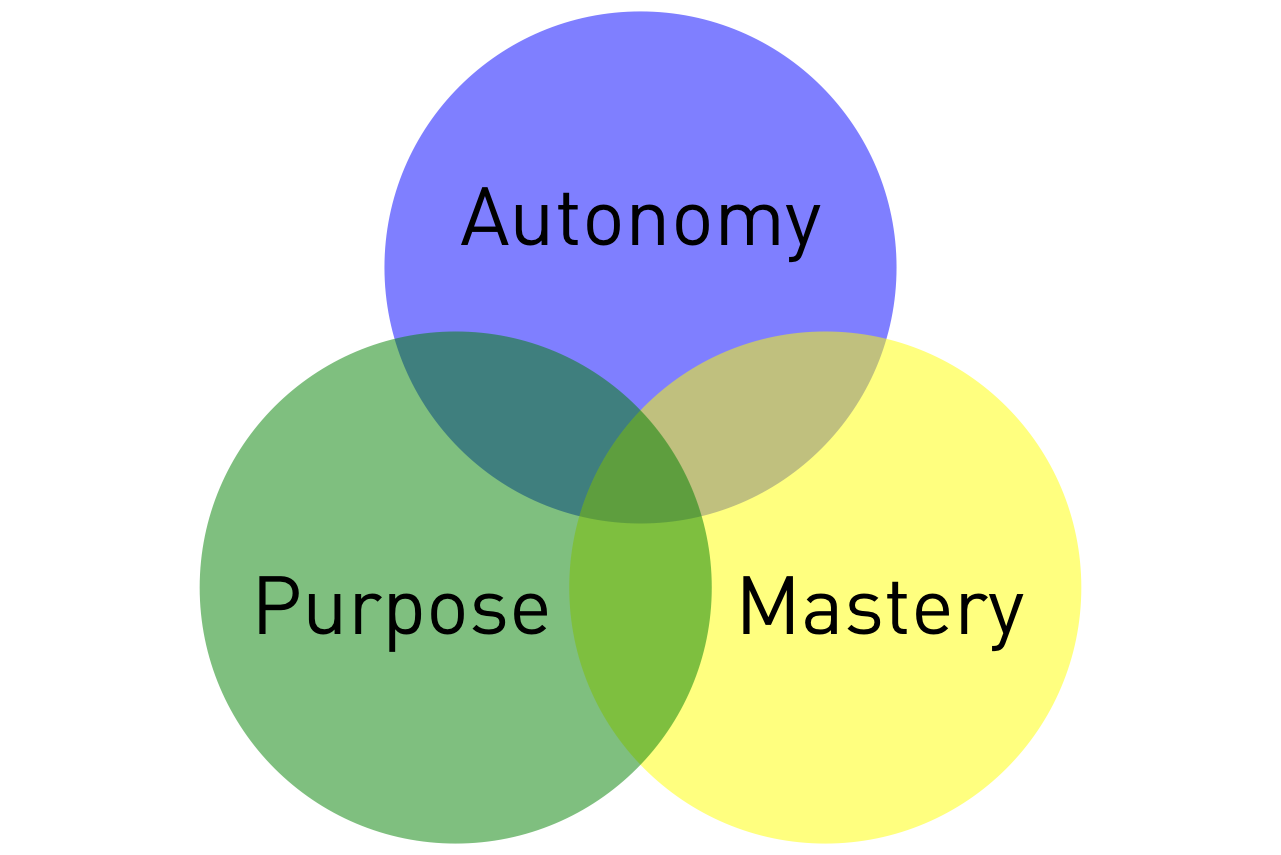

Market Socialism, applied to SMEs, gives us Worker Cooperatives. Worker Cooperatives (or simply coops) are enterprises that are owned and self-managed by their workers. Coops combine the Marxist notion of worker control over the means of production with a free market mode of trade & distribution. All decisions of self-management are made democratically by worker-owners who, in the case of SMEs, may have a one-person-one-vote system of direct democracy. Coops tend to heavily satisfy writer Daniel Pink’s theory of motivation where he suggests that for workers to be motivated, they must have autonomy, mastery, & purpose.

Autonomy exists due to relative equality as every member of the coop is a worker-shareholder and thus answers not to anyone above them, but to their co-workers. This gives a sense of entitlement of belonging to the enterprise; a collective; a society.

Mastery is achieved when a person wishes to undertake a task and starting a cooperative requires knowledge of how to do a particular task. Producing as part of a coop gives access to synergy and increased social capital that facilitates mutual aid.

Lastly, coops give workers a purpose to work. If a worker makes minimum wage or a fixed salary, there is no real incentive to produce higher as their pay is static. However, if how much money you make depends on how much you work, and how much money the entire coop makes also depends on how much you work, you would be compelled to work so not only you, but your co-workers also receive higher profits. This further fuels increased social capital. Thus, a method of social ownership is psychologically proven to help boost productivity.

A Case for Worker Cooperatives: SMEs and Conglomerates

Coops have been generally successful in providing communities with jobs and opportunities to make a successful living. For example, the Amul Milk Coop in India started as a dairy coop with farmers, but it has since expanded into the largest producer of milk in the world with a revenue exceeding $4.5 billion. Numerous coops have also sprung up in the US that provides services ranging from coffee and snacks, all the way to taxis. On a micro-scale, the coop movement is growing substantially in both developed and underdeveloped countries.

As our scale of view increases, so does the success of the coops. Looking at a larger scale, we find that coops don’t necessarily need to be SMEs with the amount of democratic decision-making involved in running the organization. One of the biggest successes of this hypothesis takes us to the Basque region in Spain, where the Mondragon Cooperative serves as one of the biggest employers not only in the region, but also in the country. Mondragon is a conglomeration of 114 cooperatives that manufacture all kinds of products and provides all kinds of services in 4 key areas of activity: finance, industry, retail, and knowledge. According to its website, Mondragon employs 85,000 employees, boasts a revenue of US$14.03 billion, and has an asset turnover of US$28.66 billion.

The Mondragon coop was resilient to the 2008 financial crisis, showing a strong continual growth of 7.1% and increased market shares in many regional blocs such as BRICS, where it accounts for 20% of the market share for industrial goods. This is despite Spain generally struggling following the Eurozone crisis. Furthermore, to demonstrate more corporate social responsibility, Mondragon invests in creating social services for its employees and their families, such as health clinics and schools.

In contrast to the direct democratic structure of SME coops, Mondragon uses a fairly representational democratic structure. Each coop elects a board of directors which further sends members to the General Assembly to vote on organizational matters and to elect a President, thereby creating an organized structure with a minimal democratically-elected hierarchy. Given the higher degree of work with greater expertise, the board of directors, the President, and his associates do not share equal pay. However, the ratio of wage inequality is significantly lower compared to other forms of businesses. Each BoD member, depending on the coop, has a wage ratio of between 2:1 to 4:1 when compared to their non-BoD employees. For non-cooperative companies, the ratio stands at a staggering 271:1. This ensures a fair compensation by an intensity of labor and skills while also creating an environment that encourages hard work and workplace democratic management, all while keeping inequality to a respectable low.

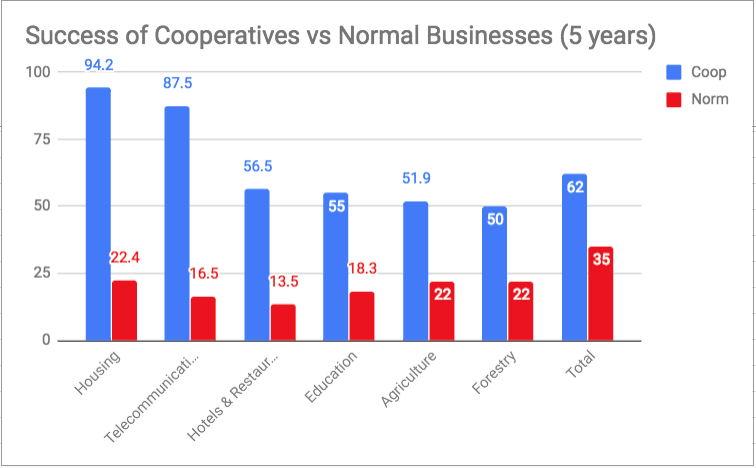

Coops like Mondragon have shown great success not only socially and monetarily, but also statistically when compared with non-cooperative companies operating in the same sectors. The Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export in Québec, in their 2008 report titled “Survival Rate of Co-operatives in Québec” indicated that the 5 year and 10 year survival rate of coops was 62% and 44% respectively, compared to conventional businesses which had a strikingly low rate of 35% and 20% respectively. The graph below provides specifics for different fields of business activity and the success rates of coops & conventional businesses, further proving that coops are significantly more successful in every sphere of economic activity. This proves that cooperatives are an effective source of long-term, stable, and sustainable employment.

The Yugoslavian Model

We have seen the success of coops on an individual (micro) scale and on a conglomerated community (macro) scale. But what would an entire economy based on cooperatives look like? While we haven’t seen a national economy completely built around cooperatives, some have been close: just look no further than the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Contrary to the USSR, where most industries and sectors were owned by the state, Yugoslav industries were mainly owned by worker cooperatives. Despite being completely ravaged following World War II, Yugoslavia became one of the most economically developed countries in Europe while having an impressively low GINI coefficient of 0.24. Everyone had access to free and quality education, healthcare, and housing. In effect, it was a welfare state run mostly on coops. However, federal complications and an ineffective monetary policy led to slowed growth after Tito’s death. Regardless, the example of Yugoslavia provides a good example of a success story for an economy mostly based off of cooperatives, hence proving that Market Socialism can, indeed, work.

Conservatives and Liberals may counter the arguments presented by saying that Socialism doesn’t work and point to the USSR, but Market Socialism is different. The Soviet Union was state-capitalist. This is defined by Raymond Williams as a state which “undertakes commercial (i.e. for-profit) economic activity and where the means of production are organized and managed as state-owned business enterprises (including the processes of capital accumulation, wage labor, and centralized management).”

Did the state, and not the general population, control the means of the production in the USSR instead of the people? Yes.

Were the employees within these state-owned enterprises paid wages, at most times fixed? Yes.

In truth, the Soviet Union followed a model of state capitalism. Socialism isn’t state ownership for profit, it is ownership by the people, and ownership by the people statistically and historically demonstrates financial, social, and economic success no matter what scale it is looked from.

Market Socialism, as an ideology, combines the best of Marxian philosophy, sociology, and ethics with the practicality of a free market, creating a seemingly more humane, equal, and sustainable form of employment for many. It has been successful in alleviating people from poverty on a micro scale, has succeeded extensively on the macro scale, and has done all the wonders it could on a national scale historically. An ideology blended into human nature, Market Socialism offers a compromise between the remnants of free-market economics in a post-capitalist context and the textbook definition of socialism. Overall, it promises to be the future for the many, not the few.

Edited by Alec Regino.