Will “Mask Diplomacy” Be Enough for China?

Can China turn the fingers pointed at it into a reassuring international hand of help?

COVID-19's consequences are still difficult to fully comprehend. Photo under public domain.

COVID-19's consequences are still difficult to fully comprehend. Photo under public domain.

In the early stages of COVID-19 in the United States, testing kits failed. “That a biomedical powerhouse like the U.S. should so thoroughly fail to create a very simple diagnostic test was, quite literally, unimaginable,” wrote Ed Yong in The Atlantic. And yet, it did. Years of budget cuts to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), even during the crisis, left the poorly led country ill-prepared for such a crisis. Since then, despite Trump’s dangerously misleading optimism, the U.S. has done nothing to uphold the global leadership role it assumed in the fight against the Ebola crisis. On the contrary. Trump invoked the Korean War-era Defence Production Act to compel the giant mask manufacturer 3M to stop exporting to Canada and Mexico, its natural USMCA allies. Allegations from Germany of “modern piracy” practices from the U.S. substantiate the Trumpism ‘America First’ and nationalist isolationism. China, in contrast, has striven in recent years towards globalisation. Xi Jinping coined China’s foreign policy ambitions as wishing to “build a community of shared destiny for common progress.” While many countries have pointed fingers at China in the genesis of the outbreak, can Beijing turn this domestic and international catastrophe into a diplomatic opportunity? Can China take advantage of the situation and fill this global leadership vacuum?

In 1990, Joseph Nye famously coined the term soft power, in contrast with hard power which referred to the military power of a country. In international relations (IR), soft power alludes to culture, economic clout, and political values, amongst other things. China is barely mentioned in this seminal article: a decade only after the start of Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening up at the end of the Cold War era and, especially, after the human and diplomatic fiasco of Tiananmen in 1989, China was nowhere near its hegemon status. Yet, 30 years later, China now ranks 27th on the soft power index. Nye’s concept was particularly relevant in the 20th century: the post-Cold War years, led by the hegemonic United States, was the scene of a gigantic conversion of old economic and political systems. The number of liberal democracies rose from about 100 to 150, free-market capitalist economies went from 40 to 100, and multinational organizations boomed, as countries increasingly gave globalism a chance. And yet, in the 21st century, attempts at democratization have failed, notably in the Arab Spring; protracted military entanglement has defined foreign policy in the Middle East; national populism has increasingly gripped Western liberal democracies such as Hungary, Poland, Italy, Austria, and the U.S.; even U.S.-EU relations have become colder. In the face of such trends, China’s rising soft power—relative especially to the U.S. who lost its index first place in 2016—could signal a significant shift in power.

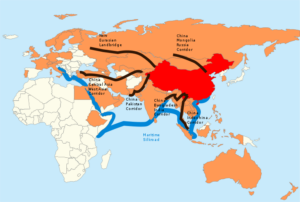

While Deng promoted a foreign policy oriented towards the slogan “hide your strength and bide your time,” Xi has fully embraced China’s ambitions to take on a global leadership role. The National Endowment for Democracy has coined the term sharp power to describe China’s policies abroad. Despite its efforts to develop soft power internationally, namely through its numerous Confucius Institutes, China’s cultural and political reach remains low internationally. While its military is increasingly present overseas, it still is incomparable with that of the U.S. abroad. Hence, sharp power describes the subtle yet very effective economic dependencies and international diaspora presence tied with China. The One Belt One Road Initiative has sparked controversy over the creation of such economic dependencies. Under this gigantic foreign policy umbrella, a massive amount of foreign investments and infrastructure projects are put together by Chinese firms and the government. Enticing short term returns had attracted mostly African countries until Italy decided to join last year, the first European nation and G7 member to do so. Furthermore, China took a decisive lead in the climate change battle when the U.S. left the Paris agreement. China backs the agreement while promoting less severe restrictions for developing countries that support its leadership. Despite this leniency towards countries that may not yet be equipped for an energetic transition—as its own coal production and consumption remain gargantuan—China has backed its diplomatic efforts with concrete actions, becoming the world leader in electric vehicles, renewable energy and energy storage. Leadership in the technology sector has not only been limited to renewable energy: despite controversies around the world, China’s lead in the 5G technology development race seems insurmountable. The Belt and Road Initiative, as well as those leadership incursions in some of the 21st century’s most important sectors, have laid the foundation for China as a credible world leader. While we may have expected a global bipolar leadership, or even a partnership like in the 2008 financial crisis or the Ebola outbreak, the U.S. (as the incumbent) and China (as the contender) have instead fallen into open confrontation, made apparent by the trade war that has been ongoing in recent years. It may prove difficult to avoid the Thucydides Trap, which has been haunting U.S. foreign affairs and stipulates that the challenge of a ruling power by another one usually ends in bloodshed.

It is in this context that China’s “mask diplomacy” must be understood. Now that it has for the most part controlled the disease, at least until a potential second wave, China has taken advantage of the lack of leadership from the U.S. to provide equipment and expertise to countries in need. Italy, one of the hardest hit countries, has severely criticized the EU and its lack of European solidarity: while Germany and France have imposed restrictions on exports of equipment, China has sold large quantities to Italy. Similar scenarios exist in other countries. China has donated test kits to Cambodia and deployed medical staff in Iran and Iraq; even Spain, whose prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, received a call from Xi to express his solidarity, stating that “sunshine comes after the storm” and potentially leading to future bilateral collaborations.

The most important PR stunt may have come from Serbia. Strongly denouncing Europe’s lack of help, President Vucic turned to China and its “brother and friend” Xi Jinping for help and equipment; a video of the President saying that Serbia could not contain the virus without the help of its Chinese brothers has 300 million views in China. Jack Ma’s foundation also pledged large amounts of equipment not only to each of Africa’s 54 countries, but also to the United States. The latter move, beyond its altruism, serves as a strong symbolic message. The relationship between the two countries has rarely hit such a low, two months after the first phase deal of the trade war. The expulsion of American journalists in retaliation to the U.S. diminishing the amount of journalistic staff within the country is one of the latest developments in this quarrel that leaves the world without the cooperation of its two greatest superpowers.

The diplomatic efforts deployed by China is gathering strong leadership credibility around the world. But is it enough to assertively and decisively take the lead in this crisis? More importantly perhaps, will the goodwill capital created by its acts of altruism be enough to surpass the U.S. and yield new alliances and partnerships when the crisis ends?

Despite all of China’s efforts, it appears that the world is not yet ready for such a power paradigm shift.

One of the main reasons is that regardless of the scale of Chinese effort, many countries will see those efforts as merely compensation for the fact that not only did the outbreak originate in Wuhan, China, local authorities also concealed it for weeks, wasting the opportunity to suppress it at its root. Another important criticism is the lack of transparency shown by Chinese authorities concerning its data: some factors, such as crematorium activity, have hinted towards a death toll that is likely higher than the official number of 3,300. China cannot hide behind the fact that Western countries were ill-prepared compared to other Asian ones to legitimize its lack of transparency. Reliable data is important as other countries’ action plans often depend on past experiences and reported data. Western countries could have been proactive in their response instead of lingering in passive wait, but they lacked the same experience and trauma that informed the preparedness of surrounding Asian countries. The U.S. and the UK have hammered these points vehemently in the last weeks, namely with Trump purposefully and consistently calling COVID-19 the Chinese or the Wuhan virus.

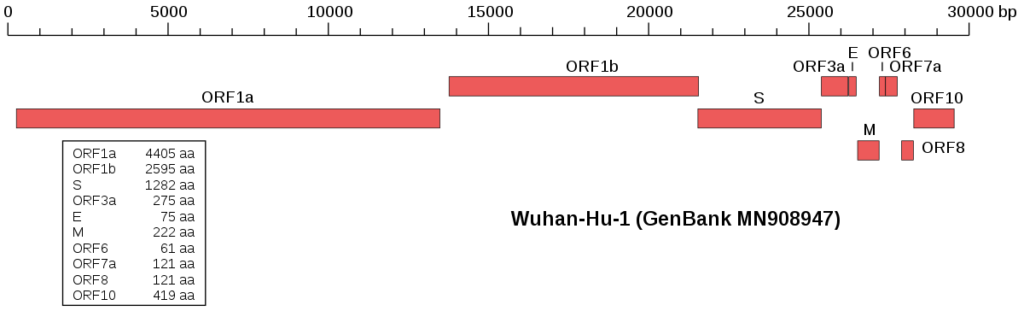

Despite the slow initial response and later concealment of some data, China’s medical and scientific efforts, notably the open-source publication of the initial viral genome, have attracted praise in the scientific community. Furthermore, as already mentioned, the situation at home is stable enough to provide the material for its “mask diplomacy”. Considering this, why is every humanitarian gesture from China received with suspicion and cynicism? Why is China not receiving more praise in Western media for its response? After decades of making China the “red devil”, especially in the U.S., shifting towards unanimous praise would be too sharp a shift. This may be one of the reasons why Vietnam, which could, so far, be used as a great success story for developing countries with fewer resources, has practically been absent in Western media outlets. The world does not seem ready to praise Communist regimes. It is true that one of the most prominent theories in IR is democratic peace, which puts forward that democratic countries do not wage war on each other. While China, through its grassroots political participation and local governments, is more democratic than what is portrayed in Western media, it remains an authoritarian state that Western countries and liberal democracies still mistrust. Ironically, the response to COVID-19 in most of those liberal democracies has been an increased participation of the State, both politically and economically. This trend, however, is likely to remain temporary and not mark a paradigm shift towards socialism with Chinese characteristics. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel stated in a rare nationwide TV address, “such restrictions can only be justified when they are absolutely necessary. In a democracy, they should not be enacted lightly—and only ever temporarily. But at the moment they are essential—in order to save human lives.”

Another symptom of the unpreparedness of the world to follow an Asian hegemon is the rise of anti-Asian racial sentiment, reminiscent of the anti-Japanese sentiment that marked Japan’s rise to the diplomatic scene in the first half of the 20th century. While this argument may be part of the equation, it is difficult to properly assess it and it is weakened by the praise that other Asian countries have received. The praise that Western media offered to South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan rather reinforce the idea that Western countries aim to follow the lead of democracies more similar and understandable to them. It is true that these countries rely on populations that are generally more deferential to their governments than Western populations are, especially considering the vivid memory of the SARS epidemic. Nonetheless, they all reacted with swift efficiency and all have the merit, in Western eyes, to have done so through democratic institutions and with the collaboration of their populations. For China, Taiwan’s success may prove a big hurdle in its diplomatic charm offensive. While WHO’s Bruce Aylward incident awkwardly reminded the whole world of the Taiwan diplomatic issue, the island has launched its own mask diplomacy offensive. Not only is the effort from China to establish the narrative that its form of government is the only one capable of efficiently containing the virus in jeopardy, it is now challenged by none other than Taiwan, its everlasting unresolved diplomatic issue and incidently a U.S. ally.

It is difficult to predict when and how the pandemic will end. It is even more difficult to predict the extent of its consequences. If a recession as bad as 1929 is what we can expect and the U.S. comes out of the crisis weakened, who knows what kind of leadership China will be able to take on? For now however, its pandemic charm offensive may be insufficient for countries worldwide to forget the errors it made in its initial handling of the outbreak. It is certainly proving insufficient in inspiring the West to overlook deep ideological and political divides that remain and may even hinder China’s long-term ability to shore up enough support to become the world hegemon.