‘Me First!’: Vaccine Nationalism and the Tragedy of Human Insecurity

Eight months into the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems have been stretched to their limits after over half a million deaths, and the global economy has taken a hit unseen since the Great Depression. Until this point, the desperate international community has viewed a vaccine as the cure-all to the crisis. Such vaccines typically require up to ten years of research and testing before reaching the market. Still, scientists internationally are racing to create a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine by next year. With more than 165 vaccines currently in development and 32 already in human trials, it has become clear that top vaccine-manufacturing nations are already competing to secure early access.

Though global health solutions warrant a coordinated global response, international cooperation to fight COVID-19 has been absent. With national interests beating out global cooperation, the global race to a coronavirus vaccine has morphed into something of a scientific gold rush with geopolitical undertones. In this risky game of “vaccine nationalism,” the scramble to a pandemic solution poses top-down consequences: a dangerous playing ground for major powers’ unchecked ambitions, and one that only breeds human insecurity.

With vaccine nationalism, self-interested states undertake a “me-first” approach to the development and distribution of vaccines and vie to secure doses of the vaccine for their own citizens before they are made available to the rest of the world. This nationalistic behaviour has been observed during COVID-19, with countries pumping the most money into their home teams.

When it comes to creating the vaccine, the US has opted to take an “America Alone” stance, which only further affirms the US’ abdication of global leadership. Acting on his pledge to deliver an American vaccine by the end of the year, President Trump in April announced that the US would be embarking on Operation Warp Speed, a federal initiative to coordinate efforts and fast-track the development of a coronavirus vaccine. Through this operation, the US has cut billion-dollar advance deals with pharmaceutical and manufacturing companies for exclusive access to millions of doses. For many observers, Trump’s Operation Warp Speed translates as an extension of his “America First” political agenda. Accordingly, with the US’ retreat from multilateralism, the overarching assumption in the international community is that Trump will seek to vaccinate Americans first with an American vaccine.

While vaccine nationalism alone poses a credible threat to populations around the globe, it also serves as a dangerous proxy for geopolitical tensions. The race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine holds great rewards for the victor; achieving such a prominent scientific victory would signify economic recovery and national glory. Inevitably, this pursuit has resulted in the deep politicization of vaccine development. While public health should indeed be paramount for leaders, adopting a zero-sum approach does more harm than good.

At the forefront of COVID-19’s nationalistic vaccine-geopolitics is the rivalry between the world’s two superpowers, the US and China. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the US has underscored an accusatory “China-virus” rhetoric that has only succeeded in pushing the rapidly deteriorating US-China relationship into a dangerous phase unlike anything seen in fifty years. In competing quests for political glory, both superpowers are deviating from the multilateral path, opting instead to pour resources en masse into their respective national vaccine efforts. For the US, winning the race before the presidential election would fulfill Trump’s “America First” agenda and secure a victory to boast over China. For China, on the other hand, the pandemic presents a unique opportunity to repent for its initial failures in Wuhan; a chance to project its soft power, rebuild its influence, and brand itself as a responsible nation, in contrast to the Western democracies that have demonstrated reprehensible pandemic responses. Beijing’s urgency has been highlighted in its plans to vaccinate its soldiers first, a military-civil fusion between the vaccine developer CanSino and the People’s Liberation Army. To be the first to the coronavirus vaccine would mean cementing China’s position as a viable candidate for global leadership — a role it has sought to fill in America’s place.

Other authoritarian rivals like Russia have also engaged in vaccine nationalism. For the Kremlin, being first to the vaccine is a matter of national prestige as it tries to assert the image of Russia as a global power of stature capable of competing with the US and China. On July 17, Russian drugmaker R-Pharm announced a licensing deal with British pharmaceutical manufacturer AstraZeneca to transfer the entire process for full reproduction of the University of Oxford’s COVID-19 vaccine in Russia. Russia’s AstraZeneca deal follows accusations from the Canadian, British, and American governments of the Kremlin’s attempt to steal vaccine data. While the Russian government denies these charges, the allegations draw attention to Russia’s nationalistic behaviour amid the pandemic. Not only does Russia’s AstraZeneca deal secure its doses of a potentially successful Oxford vaccine, but it also complements the nation’s attempts to produce its own. This proved to be the case when, on August 11, Russia announced that it was the first country to secure regulatory approval of its vaccine, Sputnik-V — an alarmingly quick, albeit rushed feat that has created worry among many members of the international community.

While these countries are doing what it takes to compete for the cure, the lower-level outcomes prove rather contradictory to the principles of global public health and vaccine development. Such projects typically entail a collaborative effort between multiple parties from different countries — not one in which wealthy nations in pursuit of political clout fail to ensure human security.

With developed nations erecting barriers to vaccine access, the issue of vaccine distribution has become a challenge of supply and demand. The most proximate consequence of vaccine nationalism sees a disproportionate burden placed onto the world’s vulnerable populations as the coronavirus cure becomes a private good inaccessible to both developed and developing nations.

Known for its notoriously high drug prices, the United States provides a prime example of vaccine nationalism’s shortcomings in wealthy countries. Medical monopolies hold the power to steer vaccine distribution and threaten to limit supply. Thus, Americans in need become priced-out. As the Trump administration attempts to buy exclusive rights to a coronavirus vaccine, it is very possible that it will be priced far too high for many Americans. In February, US Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar told Congress that the government will not intervene to guarantee the affordability of COVID-19 vaccines for Americans. In such a case, with a lifesaving vaccine inaccessible to many underinsured and marginalized communities, only more lives will be lost.

For developing countries with less bargaining power and resources, populations are left insecure as major powers rush to hoard vaccine doses. Such a failure of the international community was observed during the swine flu pandemic in 2009, when wealthier countries monopolized the initial supply of the vaccine. A repeat of the tragedy poses numerous consequences; for one, poorer nations will be forced to watch as their wealthier counterparts deplete supplies, allowing high-risk people to go unprotected in the interim of vaccine replenishment. The pressures of vaccine nationalism may even force desperate countries to block the export of vital vaccine components, leading to the breakdown of supply chains. In short, vaccine nationalism, in its paradoxical neglect of public welfare, only succeeds in extending the pandemic.

The threat of vaccine nationalism is well recognized, as some countries and health organizations have taken it upon themselves to develop preventative mechanisms. One of the most prominent of these efforts is the COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access (COVAX) Facility, a fund that, much like the US, invests into vaccine candidates–this time on behalf of the rest of the world. While such initiatives bring an optimistic light to COVID-19 and the possibility of global cooperation, the dire reality of the situation is that the latent ability of any nation to jeopardize access to the vaccine only succeeds in undermining the collective effort — thus extending the pandemic. As long as vaccine nationalism persists, nobody is safe until everybody is safe.

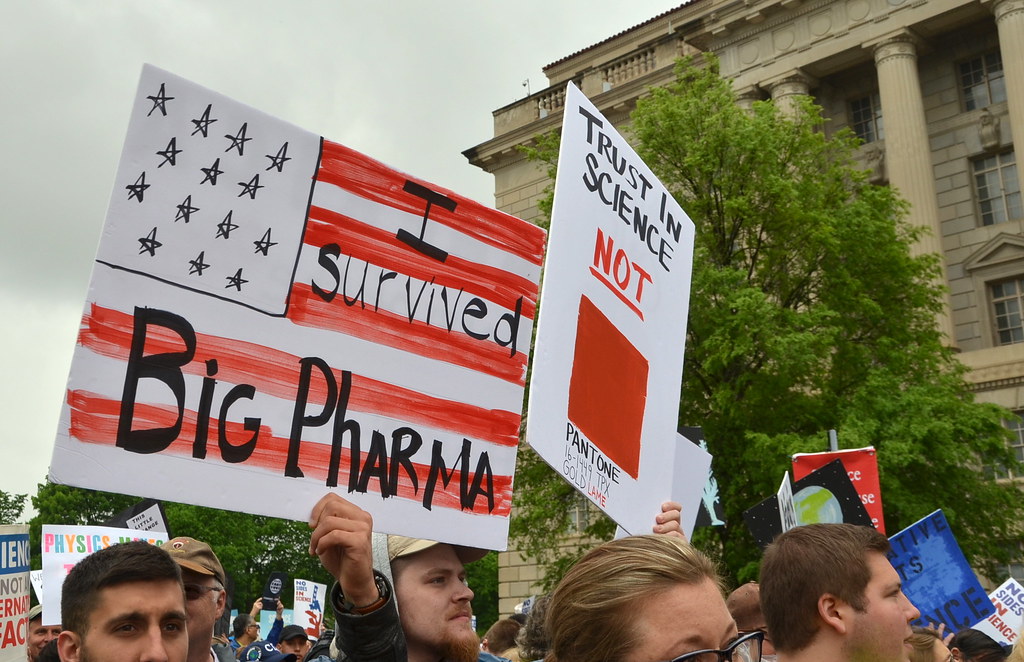

Featured Image: This untitled image is in the public domain

Edited by Nina Russell