Mixed Signals from Beijing: Taking the Recent Xi-Ma Meeting with Plenty of Salt

Taiwanese protesters protesting the Xi-Ma meeting hold up a morphed-portrait of the two world leaders.

Photo credit to 陳柏蒼 via Flickr Creative Commons

Taiwanese protesters protesting the Xi-Ma meeting hold up a morphed-portrait of the two world leaders.

Photo credit to 陳柏蒼 via Flickr Creative Commons

After 66 years of ups and downs in tensions between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC), the leaders from the two sides of the Taiwan Strait finally met and shook hands this year. On the back of a hot-and-cold history of arms buildups, cross-Strait commercial flights, mutual non-recognition, and finally mutual non-denial, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Xi Jinping and President of the Republic of China Ma Ying-jeou met in Singapore on November 7th to discuss the state of cross-Strait relations.

International praise of this historic meeting was heard across the world. And both state news media sites in China and Taiwan had headlines speaking of peace, in one fashion or another. However, the outcome of the very meeting —apart from the first shaking of the hands between the two former opposing party leaders from the Chinese Civil War— fell relatively flat. The meeting, albeit historic and precedent-setting, had little new come from it: representatives of Xi reiterated four points to Ma: the adherence to the 1992 consensus, the development of cross-Strait peace, the expansion of prosperity, and the cooperative pursuit of the Chinese renaissance. Ma, in turn, told Xi of his wishes to consolidate the 1992 consensus, reduce tension through peaceful means, increase win-win economic agreements, establish an emergency communications hotline, and cooperatively revitalize the Chinese culture.

This 1992 consensus, whose tenets both sides decided to maintain this year, was designed to seemingly put the most central question in cross-Strait relations to rest: what constitutes “China”? Through this consensus, the Kuomintang, the ruling party of Taiwan, had agreed with the CPC that there was “one China.” What territory this one China covered exactly was left up to interpretation, i.e. whether the ROC or the PRC controlled both the Mainland and the island of Taiwan. Therefore, by reiterating the 1992 consensus in this year’s meeting, both parties seemingly sought to solidify the status quo and maintain cultural unity.

In analyzing recent actions taken by the Xi-Li Administration, however, the general conclusion Taiwan and its allies might draw from this meeting is that no action from Beijing should be taken at face value. The CPC’s history of backdoor policies and mixed signals has long left Taiwan and the West guessing the underlying intentions of its actions. In September 2014, for instance, President Xi advocated a “one country, two systems” model for the reunification of Taiwan and China. Yet, a year and a month later, Xi met with Ma only to repeat his original position on the 1992 consensus —a 180-degree change of his 2014 position. This policy inconsistency deeply informs the distrust many Taiwanese citizens feel regarding Chinese policies. The short time between these two differing position predicates what many pro-independence Taiwanese believe is truly at play, namely that this month’s Xi-Ma meeting was simply a move by Beijing to calm Taiwanese fears of Chinese regional hegemony.

Uncertainty as to what Beijing’s goal is by reiterating the 1992 consensus is only further exacerbated by inconsistency in recent domestic policy projects undertaken by the Xi-Li Administration. On one hand, the Party’s recent announcements of a switch to a two-child policy and introduction of a cap-and-trade system have indicated to the West that the Administration is posturing more progressively with regards to social and environmental issues. On the other hand, however, the CPC has shown a renewed aggressive side with its tightened control over social media, its attempts to reform Hong Kong’s electoral system, and, most importantly, its recent militarization and artificial island-building in the South China Sea.

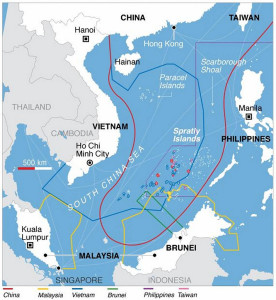

The recent Chinese military buildup in the South China Sea could be an explanation for China’s timing in holding a cross-Strait meeting. By reiterating the status quo, Xi could attempt to dissuade Ma from hastily reacting to China’s militaristic policies in the region. As it rapidly constructs entire islands equipped with ports, military facilities, and airstrips, Beijing is hoping to show as much military might as possible without igniting conflict with Taiwan. The meeting, therefore, represents a recognition on Beijing’s part that a careful balancing of Chinese interests in securing maritime ease of access and Taiwanese interests in maintaining fishing rights and possibly extracting natural resources is a suitable and low-commitment foreign policy position. It allows Beijing to not only adhere to its claims within its Nine-Dash Line but also quell international fears of an overtly revisionist China. The Xi-Ma meeting’s lack of discussion of international security issues in the South China Sea illuminates Beijing’s strategic attempt at extinguishing one volatile geopolitical question while stoking another.

These opaque, Cold War-esque policies pursued by China in the South China Sea should not be neglected by Taiwan and its allies. For fear of forceful reunification, the ROC must not be blinded by the uplifting rhetoric of a peaceful future with the Mainland coming from the recent Xi-Ma meeting. Instead, Taiwanese policymakers must beware the actions of their cousin across the Strait; they must analyze under close scrutiny each and every action Beijing takes, questioning possible hidden dual motives.

In relations as sensitive as Chinese-Taiwanese relations, a balance between optimism and skepticism must be reached. Indeed, pacifists around the world are welcome to rejoice that full-scale war currently appears unlikely between the two previously bitter rivals. However, it is also critical to look at the Xi-Ma meeting through a skeptical lens, questioning Xi’s regurgitation of a rather dull consensus from 23 years ago while simultaneously making aggressive, militaristic moves just 500 miles to China’s south. Taiwan, the United States, and other allies must take Chinese olive branches with a grain of salt, lest Chinese advances in the South China Sea and elsewhere slip under the radar.