The Mosquito vs. the Modern Nation State: Climate Change and Dengue Fever in India

"A municipal worker fumigates a residential area to prevent mosquitoes from breeding in New Delhi on Sept. 7, 2015." Tsering Topgyal—AP

"A municipal worker fumigates a residential area to prevent mosquitoes from breeding in New Delhi on Sept. 7, 2015." Tsering Topgyal—AP

"Away with a pæan of derision You winged blood-drop. Can I not overtake you? Are you one too many for me Winged Victory? Am I not mosquito enough to out-mosquito you?"

So says the penultimate stanza of D.H. Lawrence’s 1920 poem The Mosquito, which reflects upon the insignificant yet seemingly defiant nature of the “winged ghoul” and its “hateful little trump.” Lawrence manages to capture humanity’s ancient adversary – a small insect with a significant impact on human history. Today, their perverse dangers continue to threaten advanced nation-states – states that have otherwise survived colonialism, natural disasters, the slave trade, proxy wars, trade embargos, despotic regimes, and economic recessions. Their range is impressive, aided by travel and exploration: even previously isolated island states have seen increases in invasive mosquito species over the past few centuries, largely due to Western exploration.

Zika continues to rip through South and Central America, with no clear answers in sight. In Africa, the burden of diseases transmitted by infected mosquitoes is disproportionately high: 90% of malaria deaths occur on the African continent, while others still manage to keep hold in tropical or sub-tropical environments: yellow fever, chikungunya, and dengue, to name a few. In recent years, these viruses have expanded in geographic range and have even surged in areas where severe dengue outbreaks were relatively rare, as demonstrated by the recent outbreaks of dengue virus in India.

Of course, it is hardly a surprising fact that the Indian subcontinent shares a burden of tropical disease given its favourable temperature, humidity, and precipitation patterns which allow mosquitoes to thrive. What is perhaps more shocking is the revelation that some of these aforementioned diseases, such as Dengue fever, are on the rise, likely as a result of changing climates. According to the CDC, dengue virus is already a leading cause of illness and death in tropical and subtropical regions, with as many as 400 million infected with dengue hemorraghic fever per year. While the disease itself has been around for centuries, the rise of the global trade industry and increased urbanization let to higher transmission rates. Today, about 40% of the world’s population live in high-risk areas.

A new vaccine exists, and while efforts to control the primary mosquito vector, Aedes aegypti, have shown some effect, the global burden of the disease has increased drastically in the past few years which will only get worse in the current climate: according to a recent review in The Lancet, the public health impacts of climate change are predicted to worsen in the future, spurring an increased capacity for transmission of dengue by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. While the review outlines the importance of financing resilience, public health research, and adaptation measures, the urgency of the issue is not quite there.

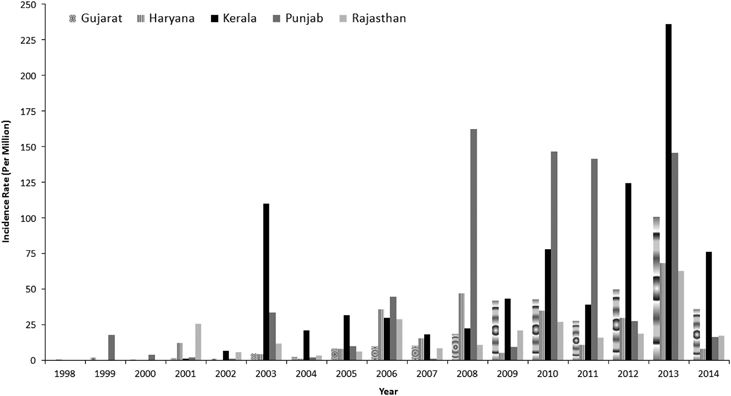

Climate change poses multiple public health threats to humanity including heat waves, changes in labour capacity, extreme weather events, food insecurity, and climate migrants, disproportionately affecting the vulnerable, low-income populations. So it is with India, which, while having stark and widespread economic disparities in many regions and widespread urban squalor (also projected to increase), is also poised to be one of the countries most affected by climate change. This combination of socioeconomic, climate, and demographic factors is what influences disease distribution. One study has noted that the global incidence of dengue has increased 30-fold over the past few years, suggesting harmonized surveillance and improved vaccination campaigns (though the new vaccines are not projected to be released in India until 2019/2020).

In 2016, it was reported that India had the world’s highest dengue burden with over 11,500 cases. However, India is not isolated in its risk for dengue. A warming planet could not only lead to a strengthened grip of dengue in India and other tropical regions, but also to the spread of dengue to Europe and high-altitude mountainous regions. While climate change can answer many questions regarding the spread of the disease, it is ultimately the effect of poor urban planning, accumulation of waste, and poor sanitation practices which allow dengue to establish itself in regions like India. Urbanization and increased international travel also work in concert with changing climates to aid in the spread of the disease. Indeed, cities provide the perfect environments for Aedes mosquitoes to breed and unlike the malaria-carrying Anopheles mosquito, Aedes aegypti bites during the day, making vector control using traditional methods such as bed nets ineffective.

Chemical control through insecticides is a popular prevention to date (although these come with their own slew of problems), while another emerging technique which has proven itself to be highly effective is the use of sterilized male mosquitoes to control future breeding. The effect of these mutant insects on the greater environment is not yet known. There is also a growing call for better collaboration between public health scientists, biologists, and virologists.

Proactive environmental management and community participation have also shown to be effective in dengue control. In India and elsewhere, awareness campaigns regarding mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue have shown some success, urging citizens to cover exposed skin and to engage in clean up any collected water which may become a breeding place for the insects. A case study in Vietnam (also a victim of rising dengue outbreaks) showed that cleaning outstanding water and introducing predators which feed on mosquito larvae eliminated the incidence of dengue fever in 40 of 45 tested communities. Better sanitation resources and waste management systems in cities will also be critical in the fight against dengue epidemics. Access to piped water might also influence dengue incidence.

Some have pointed out that, in the public health interest of international states to lessen disease mortality, states should be obligated to assist vulnerable and low-resource areas in preventing mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue. Within states, improving structural inequalities that pre-dispose impoverished populations to dengue fever infection is necessary. However, these goals are rather nebulous and not well-defined. In general, without a coherent response to climate change and its exacerbating impacts on human health, billions of lives are jeopardized. Dengue itself is considered a neglected tropical disease (NTD), one which receives much less funding than HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. Moreover, compared to these three diseases, it has a much smaller mortality rate. However, this does not cheapen the risk NTDs like dengue pose, for if anthropogenic climate factors truly do increase transmission rates into the near future, then it deserves a larger share of the global research agenda. Otherwise, larger populations of people will be placed in peril, imposing a higher burden of existing cases for nations to tackle, and in matters of public health, no nation is an island.

Edited by Marissa Fortune.