Not So Sharif: “Fontgate”, Praetorianism and Illiberal Democracy in Pakistan

The resignation of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif over his family’s offshore wealth revealed by the Panama Paper leaks has plunged Islamabad into a protracted political crisis. Coupled with Donald Trump’s public accusations that the Pakistani deep state nurtures ‘terrorist enclaves’ on its soil and threat’s of pulling military and financial aid has only worsened civil-military relations. Pakistan’s constitutional order, economic growth, foreign policy choices and civilian/military relations will all be shaped by the outcome of the scheduled 2018 elections.

Calibri and the 2018 general election

The Pakistan Muslim League (PML) has the benefit of incumbency: a stellar economic track record (5% GDP growth, the lowest inflation, and interest rates in decades) and political control in Punjab. However, the disqualification of Nawaz Sharif by the Supreme Court has magnified tensions within the Sharif clan and amongst the PML’s powerbrokers. Staying true to its dynastic DNA, disqualified PML party leader Nawaz Sharif nominated his ambitious younger brother Shahbaz Sharif, the Chief Minister of Punjab, the most populous and politically significant of Pakistan’s four provinces, as the next Prime Minister of Pakistan.

To some, Shahbaz is seen as more disciplined than Nawaz and could serve as a steady-hand before next year’s elections, but to others, his nomination is seen as a cynical play by the Sharif clan to cling to power amidst corruption allegations. Nawaz Sharif’s political heir, his daughter Maryam Nawaz, is also ensnared in a money-laundering scandal, as are his two sons. The scandal originates from 2016’s Panama Papers scandal where thousands of financial records (detailing instances of fraud, tax evasion, and offshore accounts) were released to the public with the names of world leaders, politicians, celebrities, and CEOs on full display.

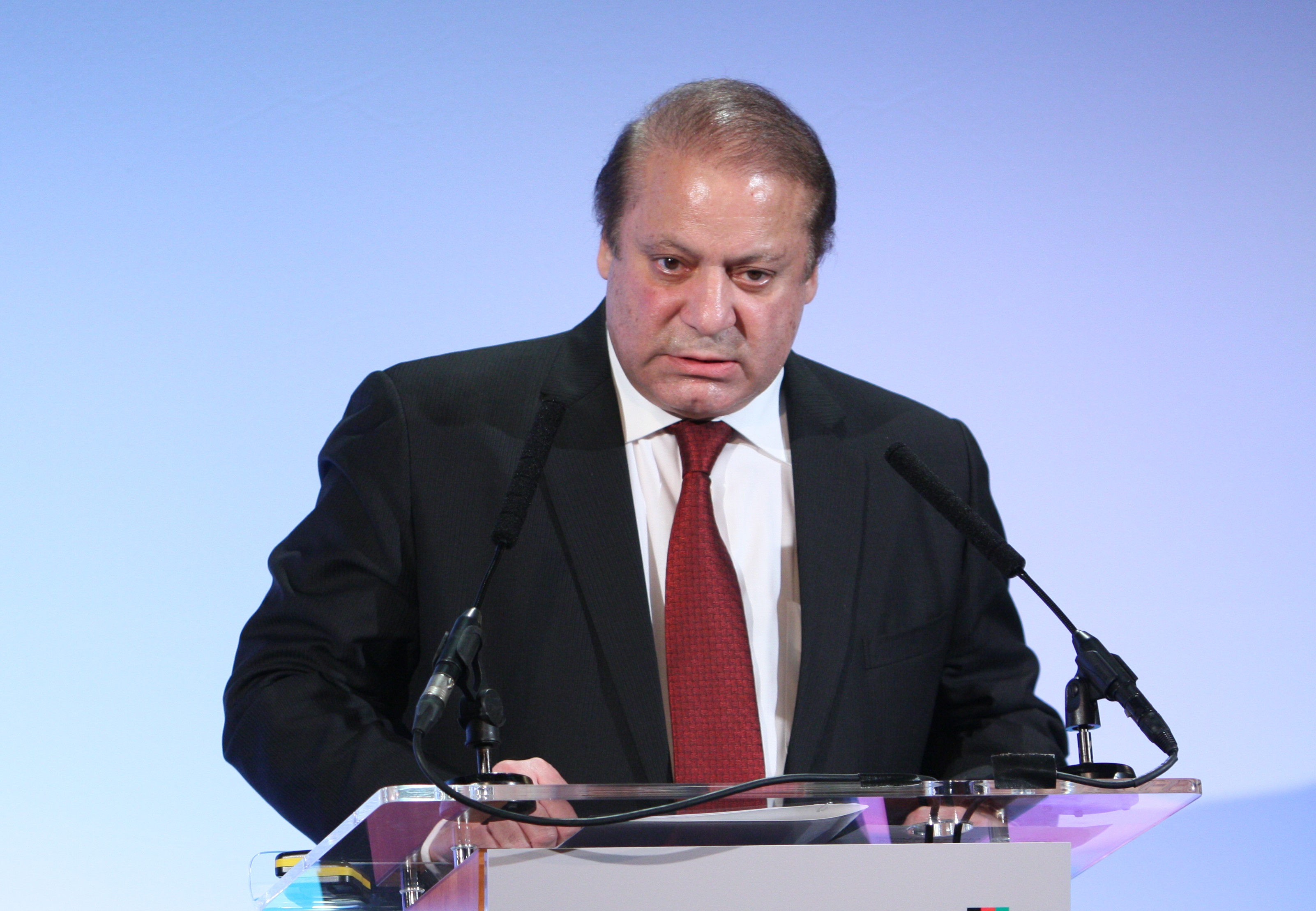

Image Credits: https://flic.kr/p/qaEpPv

Records of Nawaz Sharif’s children’s shady Virgin Island offshore accounts, dummy companies and luxury apartments in London were circulated across the Pakistani cyberspace with opposition lawmakers calling for Sharif’s permanent resignation from public office. The Joint Investigation Team (JIT), the legal taskforce responsible for investigating the Sharif case, discovered numerous irregularities between known and declared sources of income and wealth of the Sharif family. Alleged 2006 trust deeds signed by Maryam Nawaz were proven to be forged. The deeds were written in the Calibri font, which did not even exist until the launch of Windows Office 2007. After the allegations went public, the font’s Wikipedia was edited numerous times with the font’s creation date mysteriously shifting back and forth until Wikipedia was forced to lock the page (don’t believe everything you read on Wikipedia!).

Despite the disqualification of Nawaz Sharif from office and the overwhelming evidence against his children, the dynasty still looks to continue. Earlier this month, the Pakistani government amended Election Bill 2017 through the National Assembly, which conveniently allows disqualified politicians to hold public office and head political parties. It’s clear this law was created to accommodate one person: ousted PM Nawaz Sharif. What would have been considered the irreversible end to any other politician’s career is nothing but a blip for the ruling elite of Pakistan. Enraged by the shameless manipulation of legislature, opposition lawmakers tore up copies of the bill in front of the National Assembly and threw them at the Assembly speaker’s podium after the announcement of the bill’s passage.

The rumour grapevine in Islamabad alleges that the Pakistani military elite, unhappy with Nawaz Sharif, wants to engineer a coalition government led by former Pakistani cricketer turned politician Imran Khan. Ironically, October 2017 is also the eighteenth anniversary of the overthrow of yet another Muslim League government led by Nawaz Sharif, in a military coup d’état where General Parvez Musharraf seized power. Khan’s reformist PTI party could steal votes from the PML even in its stronghold of Punjab, particularly among young and urban middle-class voters. The PTI has a solid vote base in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, where it has demonstrated a credible governance track record. This could persuade Pakistan’s powerful military and intelligence establishment to support a PTI government, possibly in coalition with smaller parties. Imran Khan’s squeaky-clean image sharply contrasts with the messy, corrupt reputations of both Nawaz Sharif and former President Asif Zardari of the PPP. This “Mr. Clean” image could be the game changer he needs to emerge as the next Prime Minister of Pakistan as long as he does not challenge the national security/foreign policy of the Military establishment and presents a coherent economic plan that continues the PML’s reformist, pro-market policies.

The 2018 elections will also be decisive for the Pakistan Peoples Party’s (PPP) 29-year-old chairman Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, the novice political heir of former President Asif Zardari and assassinated Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. 2017 is also the fortieth anniversary of the military coup d’état that overthrew Bilawal’s maternal grandfather Z.A Bhutto, later hanged by military dictator General Zia ul-Haq who himself perished in a suspicious plane crash in August 1988. Bhutto is confident that his family’s party will succeed in the upcoming 2018 election and with crowds averaging in the thousands, it would be hard to disagree. If there is a recurrent theme in Pakistani history, it’s the occurrence of serial coup d’état’s against civilian governments led by the heads of rival political dynasties – the Sharifs and the Bhuttos.

To read more about the Pakistani military’s invisible hand in domestic politics, refer to this article.

The return of military rule?

Parliamentary democracy in Pakistan has been stunted by periodic failures of governance, a corrupt political culture, dynastic or ethnic-based political parties, civil war (Balochistan since the 1970s, Sindh since the 1980’s and the Frontier Province since the 2000’s) and the infrastructure of a “garrison state” whose Praetorian rulers seek control of strategic nuclear assets and the conflict with India over Kashmir. Pakistan’s military intelligence services, the ISI, has also financed and armed terrorist groups like the Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani network and the Lakshar-e-Tayeba to achieve political ends in both Afghanistan and Kashmir. The ISI is also a dominant, sinister force in domestic Pakistani politics who will be a key player in the 2018 elections and in the Pakistani state’s relations with Beijing on the projects of CPEC and Washington, as the Trump White House unwinds military involvement in war-torn Afghanistan.

Image credits: http://bit.ly/2wXHzBt

Elections alone cannot resolve Pakistan’s deep political cleavages. In fact, they can exacerbate them. The December 1970 election led to the secession of East Pakistan (Bangladesh) after a catastrophic war with India in 1971. The 1977 election led to allegations of massive vote-rigging by Z.A Bhutto’s PPP government and its later overthrow by the military regime of Zia Ul-Haq [1]. General Parvez Musharraf’s plans to lead as a civilian President ended in the collapse of his military government after a mass protest movement led by the judiciary. Nawaz Sharif has been Prime Minister three times since 1990 and never once completed a term in office – like every other civilian ruler in Pakistan’s history.

Pakistan’s current political impasse naturally increases the power and leverage of its military high command. The Generals in the Rawalpindi GHQ always accrue power when the civilians in Islamabad’s Prime Minister House or National Assembly get mired in constitutional and governance quagmires. General Musharraf has even boasted that only military rulers in Pakistan can resolve the ‘mess’ created by civilian politicians, even though Article 6 of the Constitution defines an extra-judicial seizure of power as “high treason.”

The political track record of Pakistan’s military governments has always been dismal. Field Marshal Ayub Khan mismanaged the 1965 war with India and ignored Bengali demands for political representation. General Yahya Khan launched a genocidal assault in East Pakistan in March 1971 that culminated in yet another war with India, and the cession of Bangladesh. General Zia Ul-Haq allied with Regan’s CIA to launch the “jihad” against the Soviet Union’s occupation of Afghanistan, a policy that bequeathed Pakistan with a generation of Islamist terror and a ‘Kalashnikov’ gun culture, coupled with radically conservative Islamist domestic policies that set Pakistan back decades. General Musharraf bungled the Kargil War with India in 1998 and did not curb the power of the military’s proxies in Afghanistan and Kashmir.

There is no ‘military takeover’ or ‘blood right dynasty’ solution to the political woes of Pakistan – the 50,000 lives lost to the Pakistani Taliban and sectarian terrorists since 2001 are a testament to the abject failure of the military’s armed ‘proxies’ in Afghanistan and Kashmir to gain ‘strategic depth’ in the ‘existential’ war with India. Worshipping political dynasties like the Bhuttos and the Sharifs, who have done nothing but leech capital resources from the people of Pakistan to fill their own (and their friends’) pockets, will not solve the now-institutionalized levels of corruption within the Pakistani government and deep state. As in the past, Pakistani democracy will reinvent itself amid political crises, military intrigue and a general (‘s?) election.

(Fun fact: This article was written with Calibri!)

[1] Talbot, Ian (1998). Pakistan, a Modern History. NY: St.Martin’s Press. pp. 240–1.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi